Here are a few quick figures that parse the disability classifications of children with disabilities served by charter schools in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

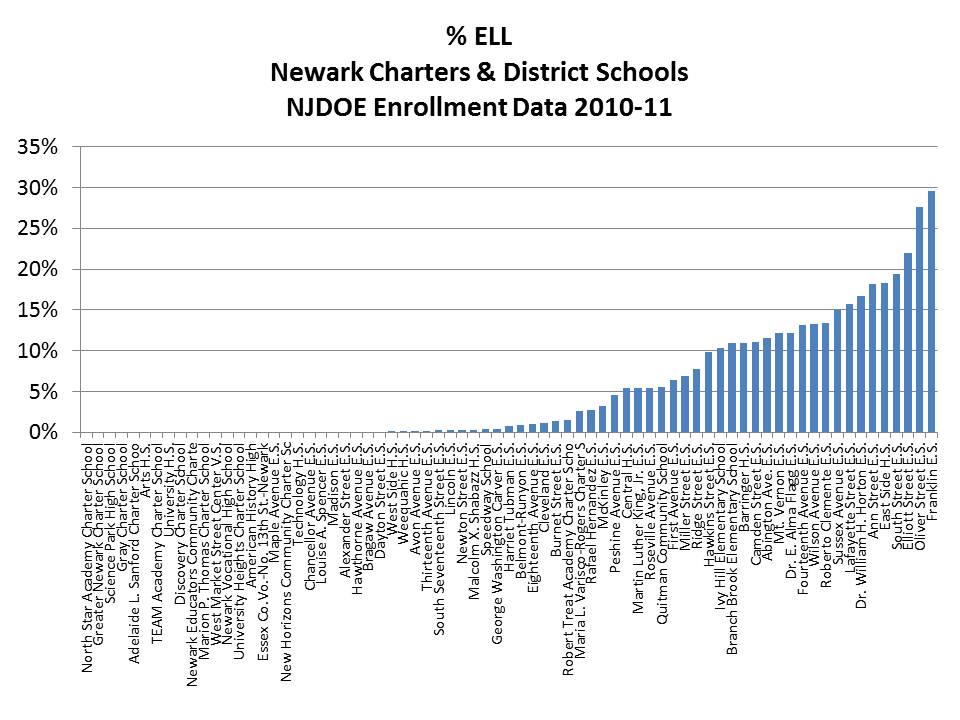

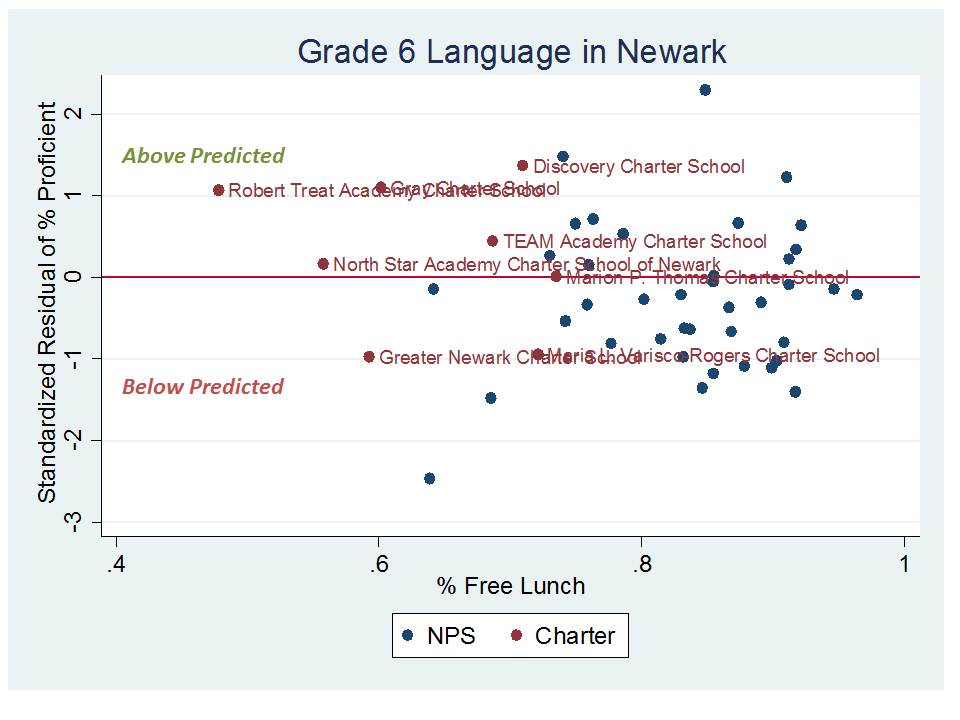

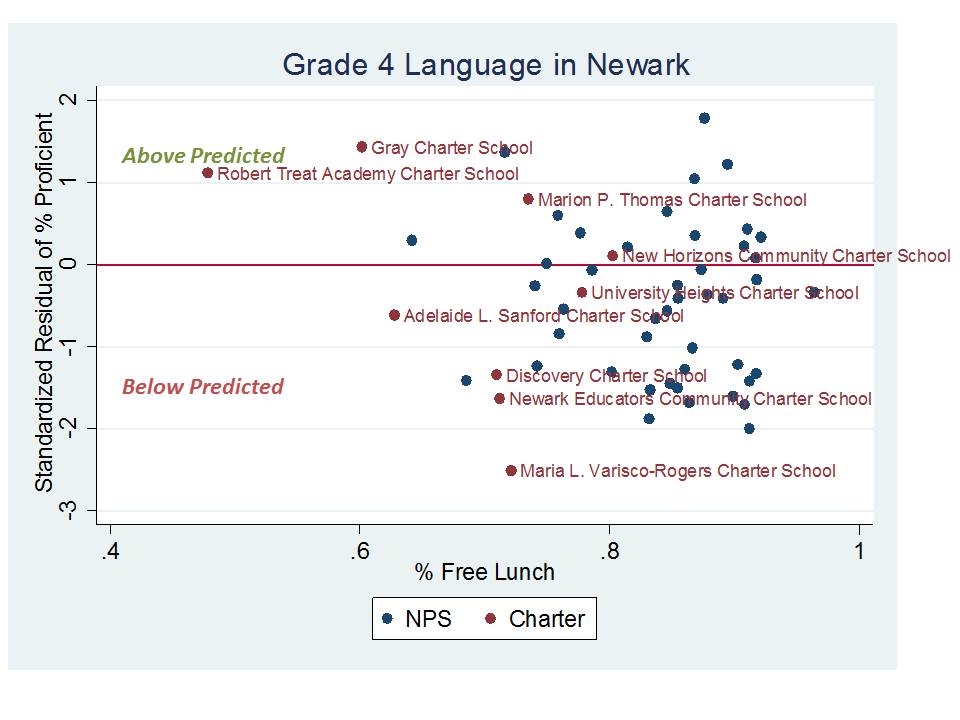

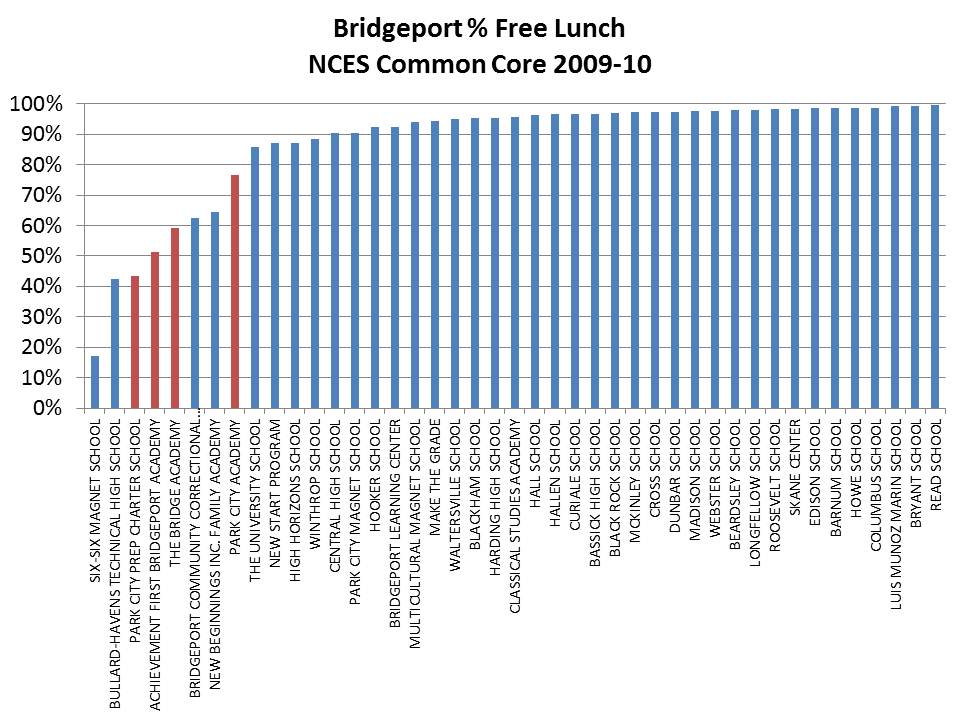

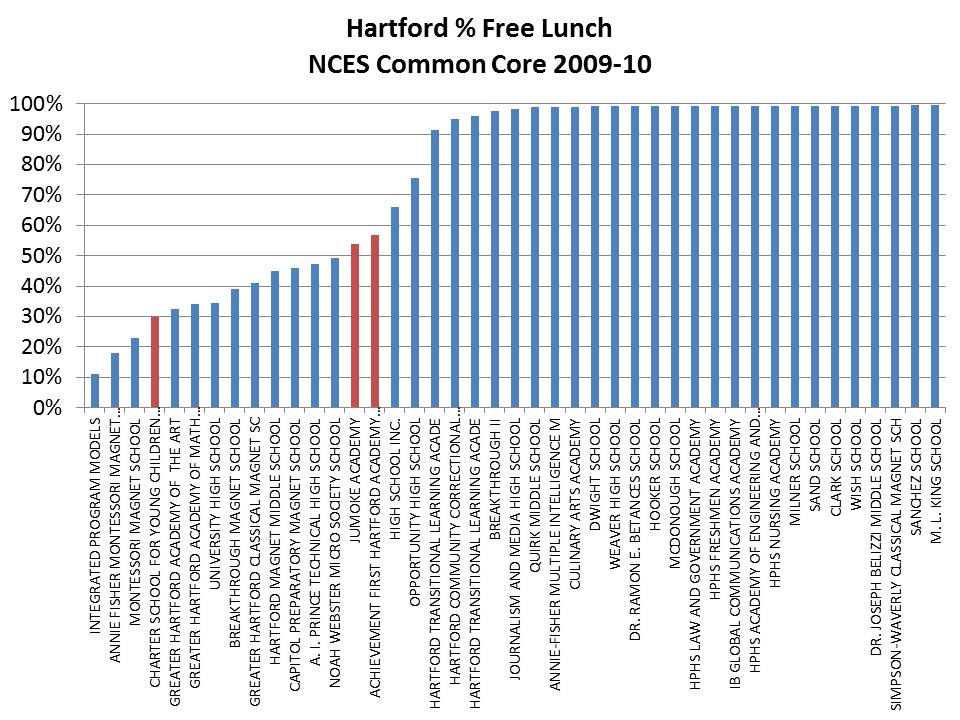

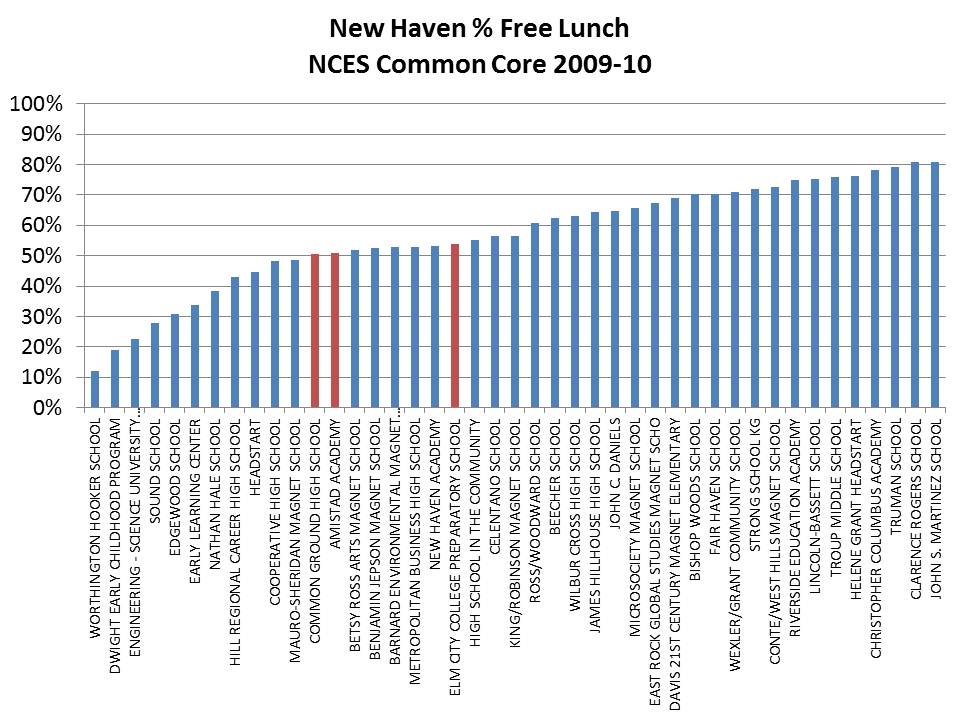

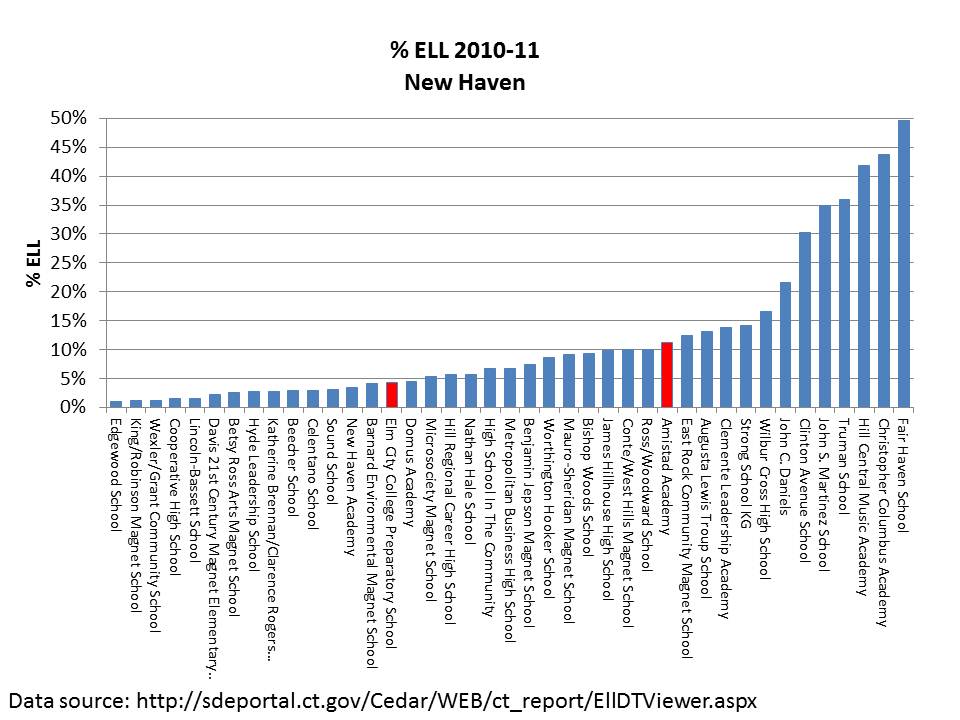

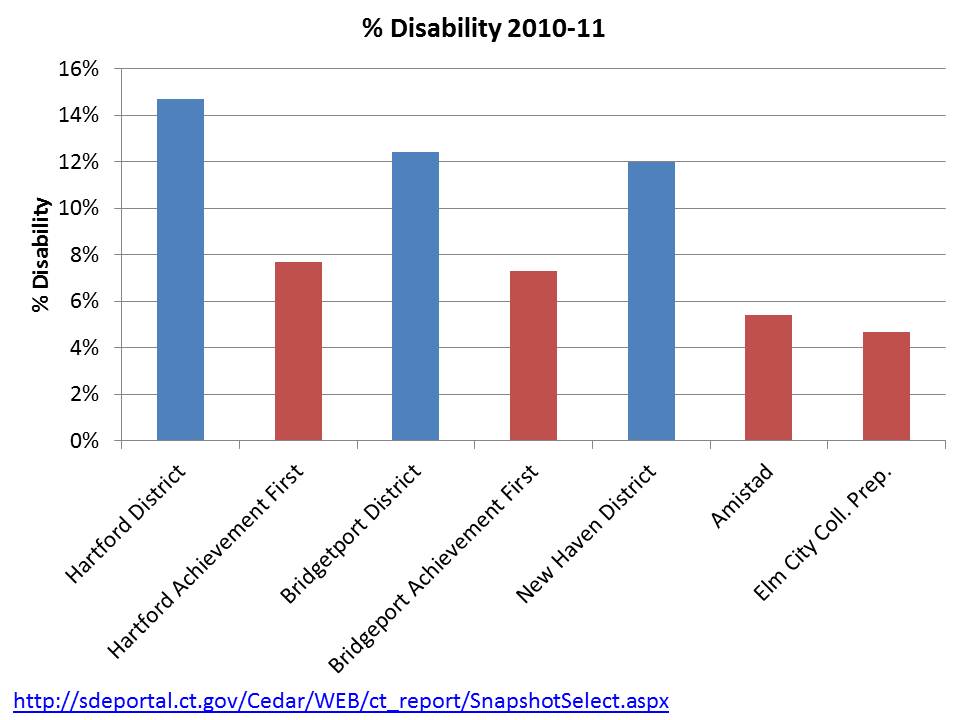

Two previous posts set the stage for this comparison. In one, I explained how charter schools in the city of Newark, NJ, by taking on fewer low income students, far fewer LEP/ELL students and very few children with disabilities other than those with the mildest/lowest cost disabilities (specific learning disability and speech/language impairment) are leaving behind a much higher need, higher cost population for the district schools to serve.

Effects of Charter Enrollment on District Enrollment in Newark:

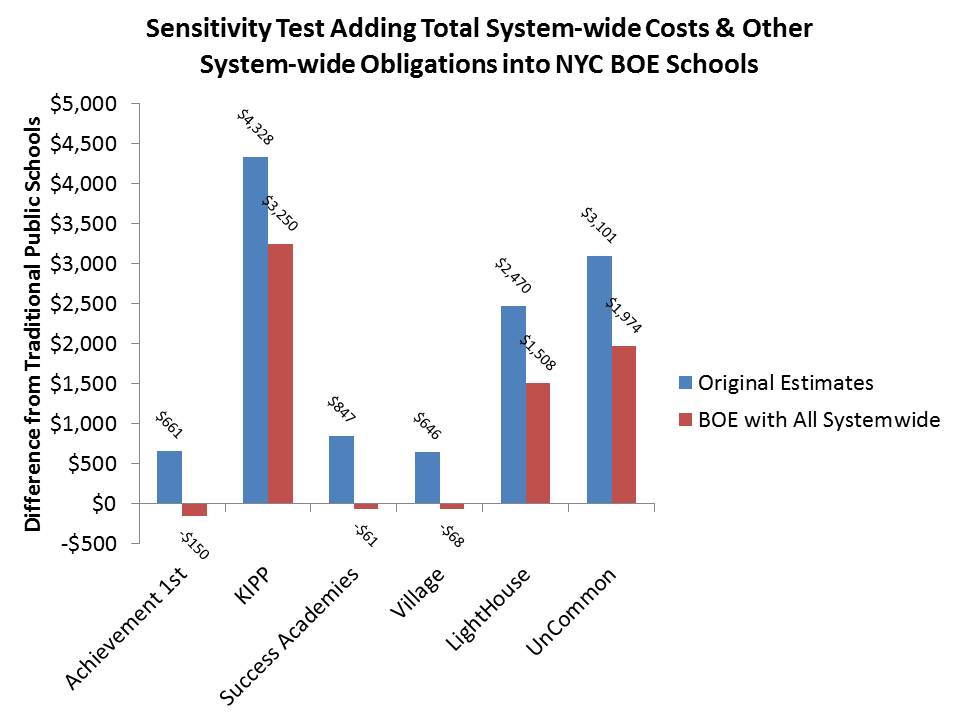

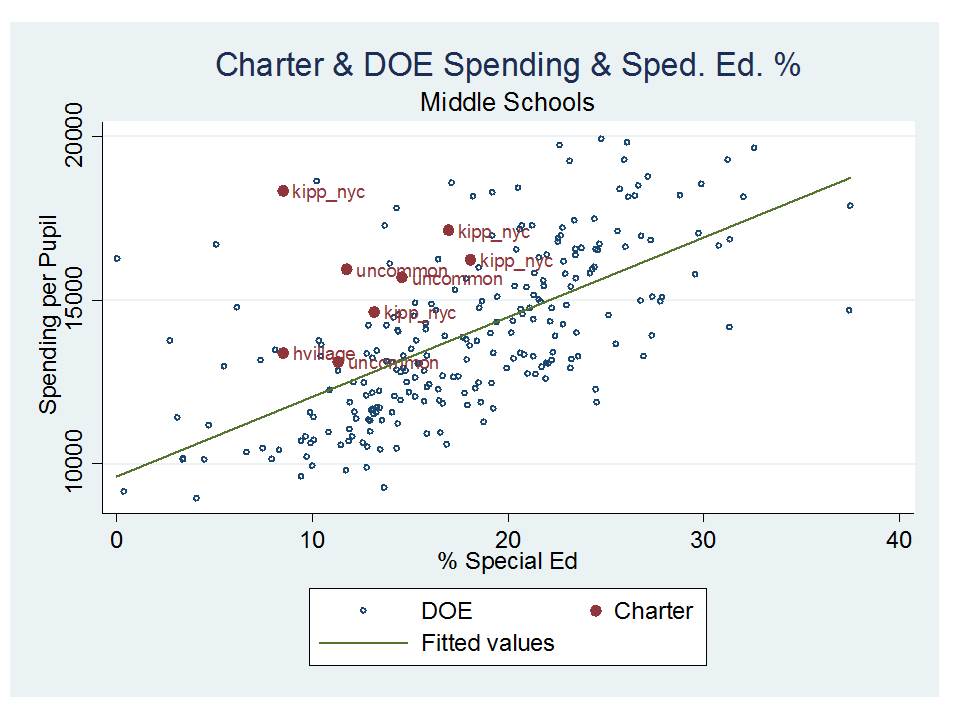

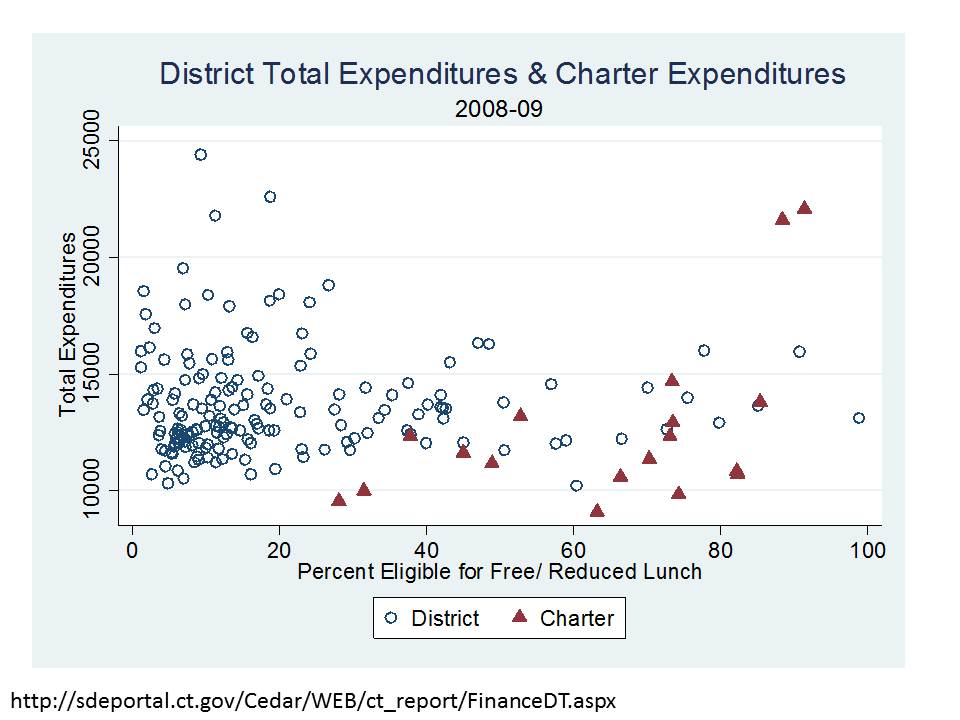

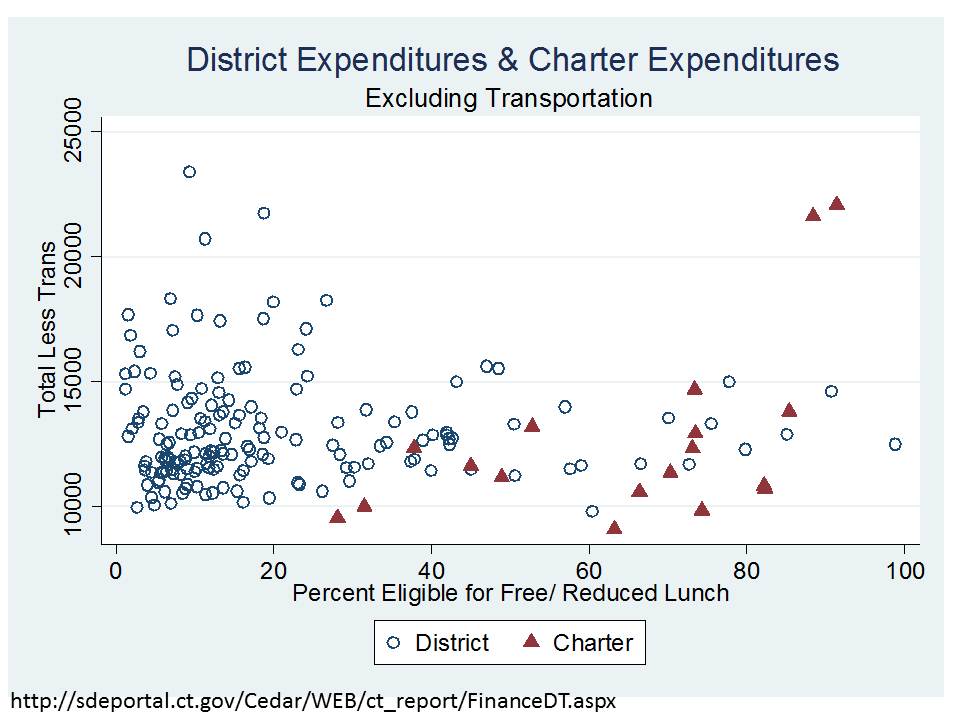

In another post, I walked through the financial implications of Pennsylvania’s special education funding formula and specifically the charter school special education funding formula on districts where large shares of low need disability students are siphoned off by charters and where high need disability students are left behind to be served by districts with depleted resources.

The Commonwealth Triple-screw:

In short, under the Pennsylvania charter school funding formula, for each child classified as having a disability and choosing to attend a charter school, the sending district must pay the “average special education expenditure” of the district – regardless of the actual IEP needs of that student. So, there’s a strong financial incentive to serve large numbers of low need special education students in PA charters. But this, of course, leaves a mess behind for local districts, who then have a far higher need special education population and have lost substantial shares of their available funding (due to a completely arbitrary and wrongheaded calculation of the sending tuition rate).

This post merely provides a few more comprehensive follow up figures on the issue of higher versus lower need disability students and charter school enrollments.

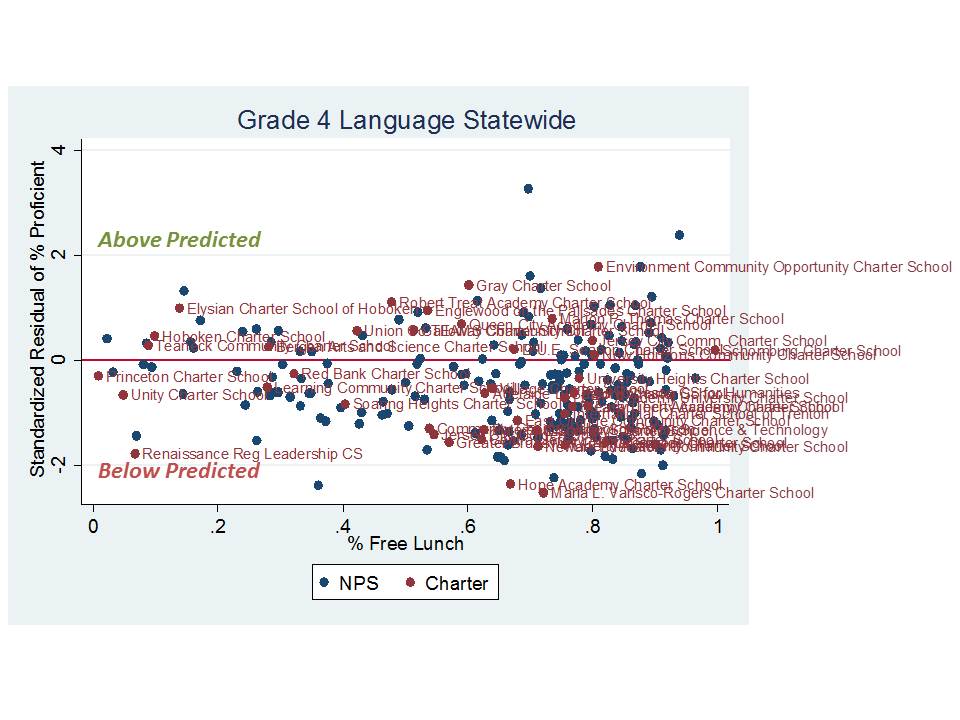

First, in New Jersey, here’s the statewide breakout of charter special education enrollments and market shares based on data from 2010 (same as used in Newark post)

- In short, charter schools in NJ serve about 1.7% of the population.

- They serve about 1.05% of the population of children with disabilities.

- AND… they serve only about .23% of the population of children with disabilities other than Specific Learning Disability or Speech/Language Impairment!

That’s a big deal! It’s a big deal because this leaves behind significant numbers of high need disability children to be served by districts. And, to the extent that charter expansion follows the same trend, this will lead to even greater concentration of children with disabilities in general in district schools and children with more severe disabilities in particular.

Here’s the average disability classification profile for NJ public districts and for NJ charter schools.

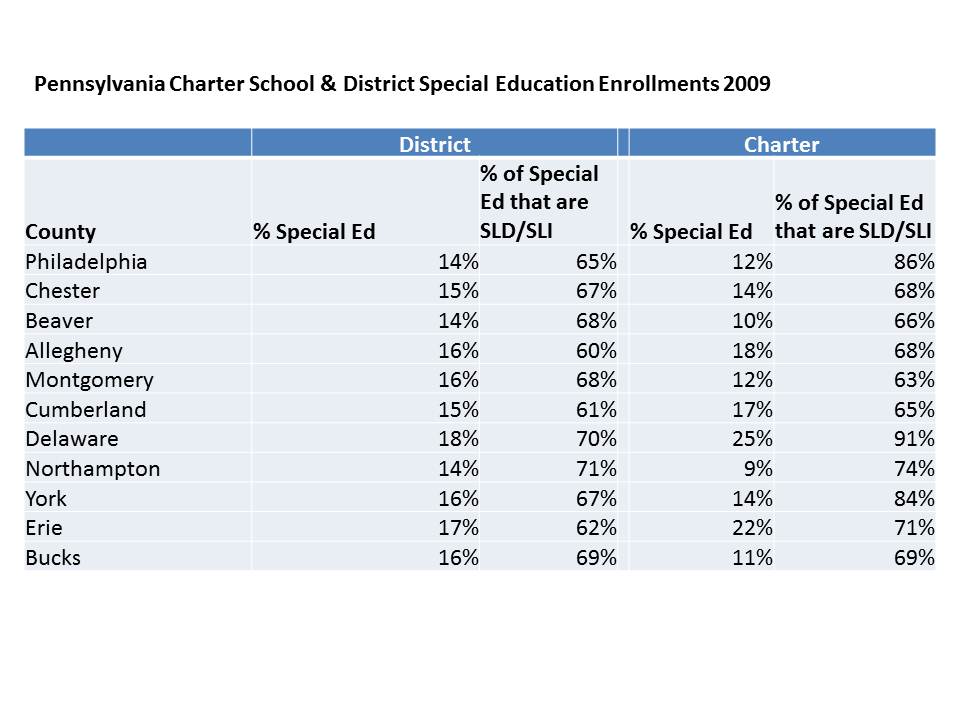

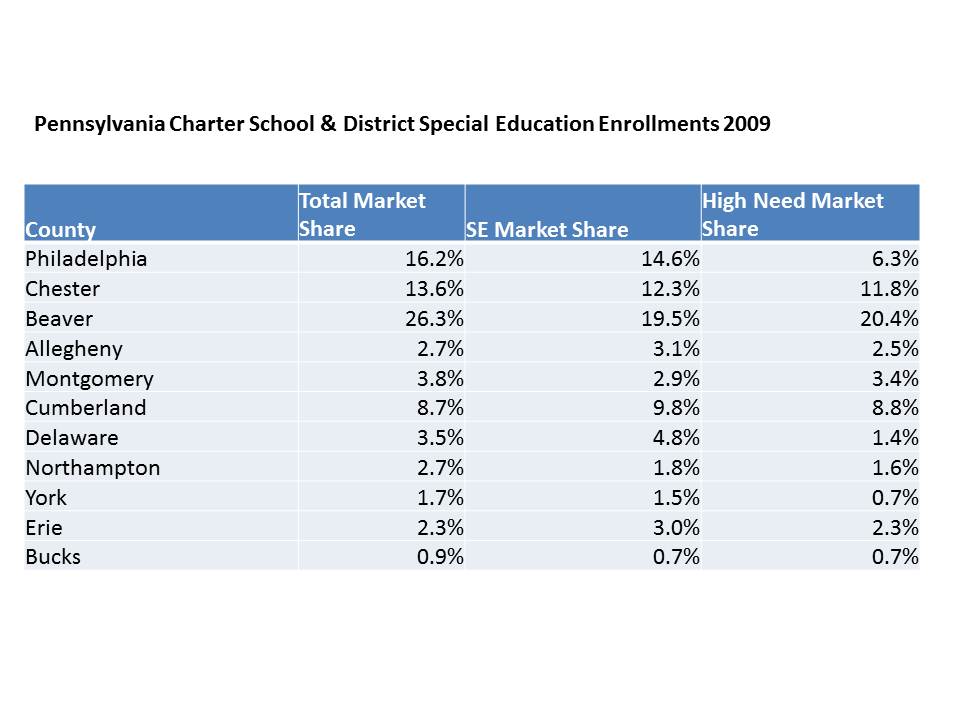

Now, for Pennsylvania, where there exists a significant incentive for charter schools to boost their special education populations but to avoid serving children with more severe disabilities. Here are the counts for counties with at least 500 students in charter schools:

Now, for Pennsylvania, where there exists a significant incentive for charter schools to boost their special education populations but to avoid serving children with more severe disabilities. Here are the counts for counties with at least 500 students in charter schools:

Here are the enrollment shares within counties:

And finally, here are the population shares served:

And finally, here are the population shares served:

So, for example, in Philadelphia county, which is the city:

So, for example, in Philadelphia county, which is the city:

- Charter schools serve 16.2% of the student population

- Charter schools serve about 14.6% of the children with disabilities

- BUT… charter schools serve only about 6.3% of children with disabilities other than SLD or SLI!

Even in those counties where charters serve a larger share of the county-wide total special education population, they only occasionally serve an equitable share of children with more severe disabilities (often in specialized schools).

In Delaware County, charters do serve a higher overall special education population share than districts in the county, but serve a much smaller share of non-SLI/SLD disabilities. And Chester-Upland in particular bears the fiscal brunt of this practice!

That said, clearly, PA charter schools are generally serving more comparable aggregate shares of children with disabilities than NJ charter schools and perhaps the financial incentive plays a role.

Again, a critical issue here is the nature of the population left behind in district schools.

These figures also dispel a common assertion of charter advocates/pundits who, when challenged as to why special education rates tend to be generally low in charters, often argue that it’s because the charters are implementing better early interventions and thus avoiding classifying children in marginal categories like “specific learning disability.” To begin with, there’s absolutely no evidence to support this claim. That aside, these figures show that in fact, many charters do seem to have plenty of students in these marginal categories. What they don’t have is students in the more severe disability categories such as mental retardation and traumatic brain injury and it is certainly unlikely that charter school early interventions are successfully preventing children from being later misclassified into these categories.

Statewide, of 724 children with TBA, only 7 were in charters. Of 21,987 mentally retarded children, only 396 (1.8%) were in charters. But about 4.1% of all enrollments were in charters.

I’ll admit… I am losing my patience on some of these issues. Excuse me for a moment while I vent. I’m losing my patience in large part because of the ridiculous responses/reactions I get every time I simply post some data either relating to charter school enrollments or finances. I seem only to get a flood of ridiculous responses when I’m presenting information on Charter schools. Not when I criticize value-added estimates, or point out misuse of SGPs. Pretty much exclusively when I present data on charter schools.

It’s time to cut the crap and start digging into what’s really going on here, and how to move toward a system that best serves all of the children rather than ignoring and brushing aside these issues and pushing forward with what appears to be an emerging parasitic model.

Let’s evaluate the incentives. And instead of protecting perverse, damaging financial incentives like those in PA, simply because they drive more money to charters, let’s do the right thing. Hey, it may be the case that charter allocations are otherwise too low, but raising them for the wrong reasons, with a wrong mechanism and with bad incentives is still, wrong, wrong and bad.

It may also be the case that the data we are using for making comparisons – using total of free and reduced lunch, rather than parsing income categories, comparing total special education rates instead of by classification, are encouraging charter operators to boost their enrollment subgroups by focusing on the margins. In which case, we need to make it absolutely clear by increasing data reporting precision and availability, that serving kids just under the threshold (or in marginal categories) isn’t enough. More fine grained comparisons are necessary!

I’ve said before that I don’t really believe that every school – every magnet school – every charter school – every traditional public school – can or should try to serve exactly the same population. I do believe there’s room for specialization in the system. I also believe that many charters that “succeed” so-to-speak, do so because they’ve figured out how to serve well their non-representative populations. And many would likely fail miserably at trying to serve children with more severe disabilities (as many district schools have).

BUT… accepting that there’s room for some specialization within the system and some uneven distribution of students is a far cry from what is now emerging, as charter market shares increase significantly in some cities and in some zip codes. And that must stop!