This week, Mike Petrilli (TB Fordham Institute) and Marguerite Roza (Gates Foundation) released a “policy brief” identifying 15 ways to “stretch” the school dollar. Presumably, what Petrilli and Roza mean by stretching the school dollar is to find ways to cut spending while either not harming educational outcomes or actually improving them. That goal in mind, it’s pretty darn hard to see how any of the 15 proposals would lead to progress toward that goal.

The new policy brief reads like School Finance Reform in a Can. I’ve written previously about what I called Off-the-Shelf school finance reforms, which are quick and easy – generally ineffective and meaningless, or potentially damaging – revenue-neutral school finance fixes. In this new brief, Petrilli and Roza have pulled out all the stops. They’ve generated a list, which could easily have been generated by a random search engine scouring “reformy” think tank websites, excluding any ideas actually supported by research literature.

The policy brief includes some introductory ramblings about district level practices for “stretching” the school dollar, but the policy brief focuses on state policies that can assist in stretching the school dollar at the state level and provide local districts greater options to stretch the school dollar. I will focus my efforts on the state policy list.

Here’s the state policy recommendation list:

1. End “last hired, first fired” practices.

2. Remove class-size mandates.

3. Eliminate mandatory salary schedules.

4. Eliminate state mandates regarding work rules and terms of employment.

5. Remove “seat time” requirements.

6. Merge categorical programs and ease onerous reporting requirements.

7. Create a rigorous teacher evaluation system.

8. Pool health-care benefits.

9. Tackle the fiscal viability of teacher pensions.

10. Move toward weighted student funding.

11. Eliminate excess spending on small schools and small districts.

12. Allocate spending for learning-disabled students as a percent of population.

13. Limit the length of time that students can be identified as English Language Learners.

14. Offer waivers of non-productive state requirements.

15. Create bankruptcy-like loan provisions.

This list can be lumped into four basic categories:

A) Regurgitation of “reformy” ideology for which there exists absolutely no evidence that the “reforms” in question lead to any improvement in schooling efficiency. That is, no evidence that these reforms either “cut costs” (meaning reduce spending without reducing outcomes) or improve benefits (or outcome effects).

- Creating a rigorous evaluation system

- Ending “last hired, first fired” practices

- Move toward weighted student funding

B) Relatively common “money saving” ideas, backed by little or no actual cost-benefit analysis – the kind of stuff you’d be likely to read in a personal finance column in magazine in a dentist’s office.

- Pool health-care benefits.

- Create bankruptcy-like loan provisions. (???)

- Tackle pensions

- Cut spending on small districts and schools (consolidate?)

C) Reducing expenditures on children with special needs by pretending they don’t exist.

- Allocate spending for learning-disabled students as a percent of population.

- Limit the length of time that students can be identified as English Language Learners.

D) Un-regulation

- eliminate class-size limits

- provide waivers for ineffective mandates

- eliminate seat time requirements

- merge categorical programs

- eliminate work rules

- eliminate mandatory salary schedules

So, let’s walk through a few of these in greater detail. Let’s address whether there is any evidence whatsoever that these policies a) would actually lead to reduced short run costs while not harming, or even improving outcomes, or b) are for any other reason a good idea.

Creating an Evaluation System

This likely requires significant up front spending- heavy front end investment to design the system and put the system into place. Yes, increased, not decreased spending. And in the short-term, while money is tight. AND, there is little or no evidence that what is being recommended – a Tennessee or Colorado-style teacher evaluation model (50% on value-added scores), would actually reduce spending and /or improve outcomes. Rather, I could make a strong case that such a model will lead to exorbitant legal fees for the foreseeable future (I have a forthcoming law review article on this topic). The likelihood of achieving long run benefits from these short run expenses is questionable at best. In fact, the likelihood of significant harm seems equal if not greater (see my previous post on this topic: value-added teacher evaluation).

Ending “Last Hired, First Fired” layoff policies

In very crude terms, this approach might simply allow a district – or entire state – to layoff senior, higher salary teachers. Yeah… that could reduce the payroll. Good policy? Really questionable! Of course, Petrilli and Roza also argue that we simply shouldn’t be paying teachers for experience or degrees anyway. So I guess if we did that, we wouldn’t generate savings from this recommendation. Silly me. One or the other, I guess.

Now, we could generate performance increases (at lower spending, if we keep seniority pay, or at constant spending if we don’t) if, and only if, the future actually plays out as simulated in the various performance-based layoff simulations which I, and others have recently discussed. The assumptions in these simulations are bold (unrealistic), and much of the logic circular.

And then there are those short-term legal costs of defending the racially disparate firings, and random error firings.

Eliminating Class Size Limits

Yes, larger classes require less spending – on a per pupil basis. Smaller classes have greater benefit (greater “bang for the buck” shall we so boldly say) in higher poverty settings. A labor market dynamic problem realized in the late 1990s, when CA implemented statewide class size reduction, was that the policy stretched the pool of highly qualified teachers and ultimately made it even harder for high poverty schools to get high quality teachers (a dreadfully oversimplified and disputable version of the story).

Removing class size limits might be reasonable if only affluent districts agreed to increase their class sizes, putting more “high quality” teachers into the available labor pool… who might then be recruited into high poverty districts (another dreadfully oversimplified, if not absurd scenario). But who really thinks it will play out this way? We already know that affluent school districts a) have strong preferences for very small class sizes and b) have the resources to retain those small class sizes or reduce them further. See Money and the Market for High Quality Schooling.

Eliminating mandatory salary schedules

It seems that in this recommendation, Petrilli and Roza are arguing against state policies that mandate the adoption by local public school districts of specific step and lane salary schedules. They really only provide one brief paragraph with little or no explanation regarding what the heck they are talking about.

I’ve personally never been much of a fan of state rigidity regarding local negotiated agreements – at least in terms of steps and lanes. Many problems can occur where states enact policies as rigid as those of Washington State, were teachers statewide are on a single salary schedule.

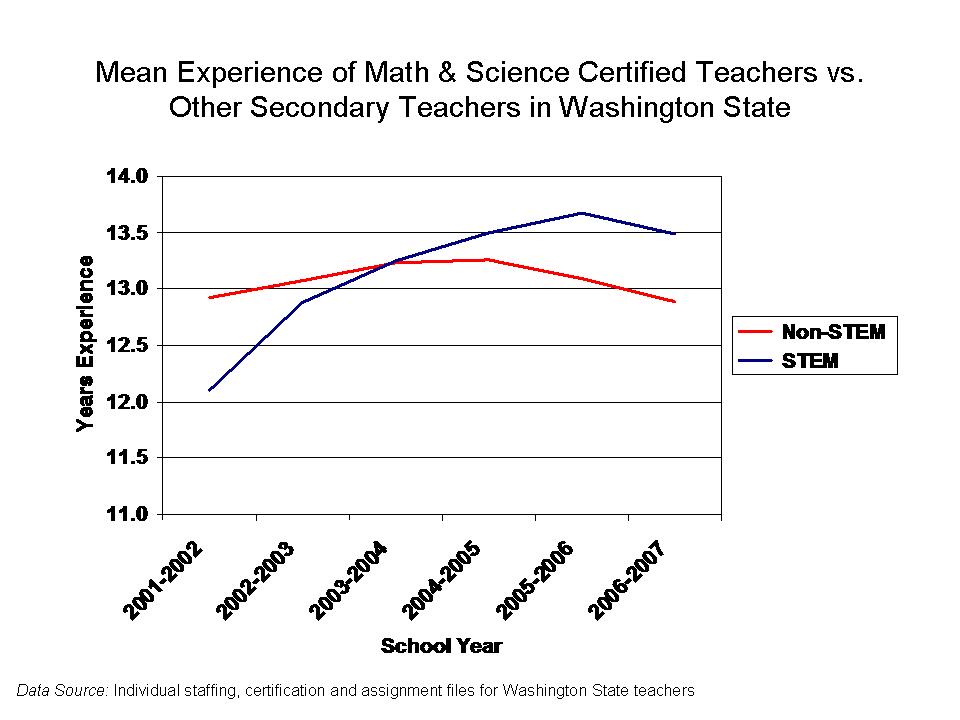

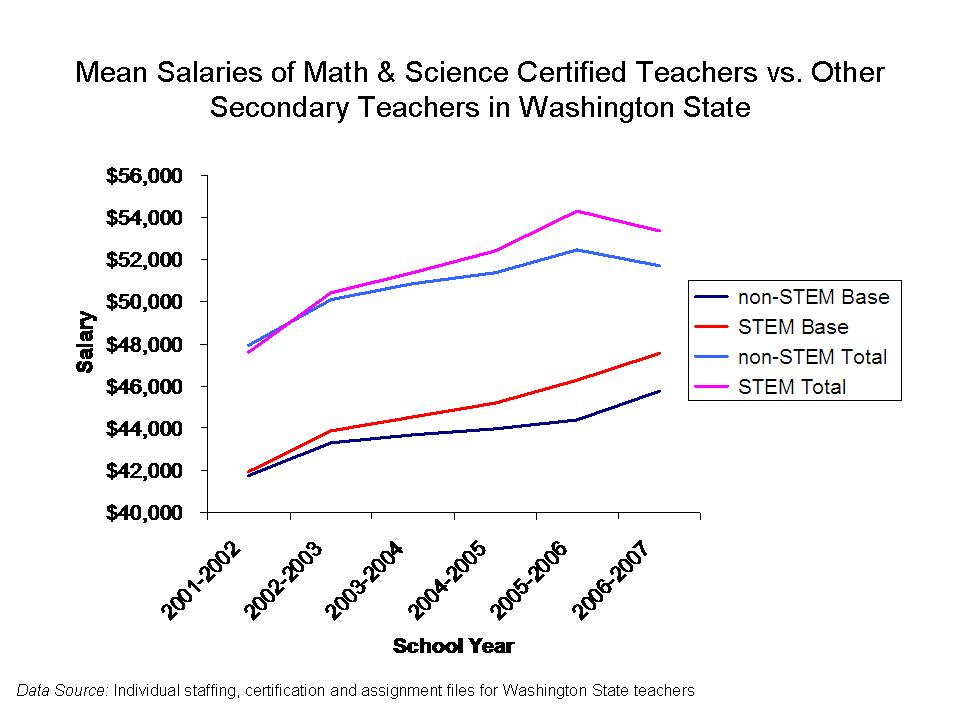

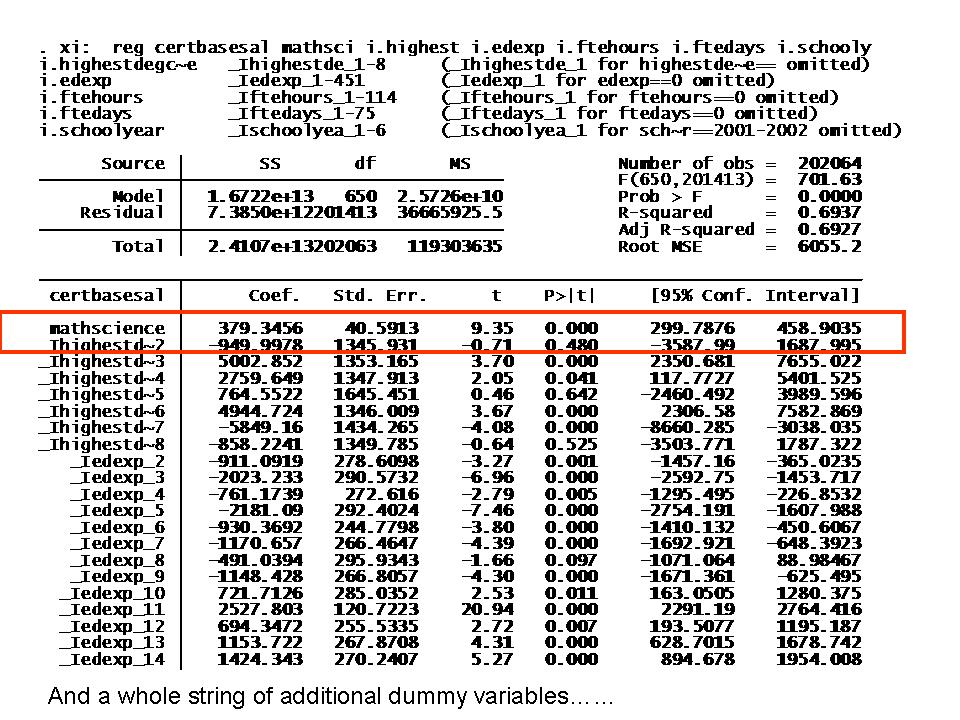

The best work on this topic (and I’ve worked on the same topic with Washington data) is by Lori Taylor of Texas A&M who shows that the Washington single salary schedule leads to non-competitive wages for teachers in metro areas, and also leads to non-competitive wages for teachers in math and science relative to other career opportunities in metro areas. The statewide salary schedule in Washington is arguably too rigid. Here’s a link to Taylor’s study:

But this does not mean, by any stretch of the imagination, that removing this requirement would save money, or “stretch” the education dollar. It might allow bargaining units in metro areas in Washington to scale up salaries over time as the economy improves. And it might lead to some creative differentiation across negotiated agreements, with districts trying to leverage different competitive advantages over one another for teacher recruitment.

But, these competitive behaviors among districts may also lead to ratcheting of teacher salaries across neighboring bargaining units, and may lead to increased salary expense with small marginal returns (as clusters of districts compete to pay more for an unchanging labor pool). For an analysis of this effect, see Mike Slagle’s work on spatial relationships in teacher salaries in Missouri. In short, Slagle finds that changes to neighboring district salary schedules are among the strongest predictors of an individual district’s salary schedule. Ratcheting upward of salaries in neighboring districts is likely to lead to adjustment by each neighboring district (to the extent resources are available). Ratcheting downward does not tend to occur (not reported in this article).

Slagle, M. (2010) A Comparison of Spatial Statistical Methods in a School Finance Policy Context. Journal of Education Finance 35 (3)

[note: this article is a shortened version of Mike’s dissertation. The article addresses only the ratcheting of per pupil spending, but the full dissertation also addresses teacher salaries]

In any case, we certainly have no evidence that removing state level requirements for mandatory salary schedules would save money while holding outcomes harmless – hence improving efficiency. Like I said, I’m not a big fan of such restrictions either, but I have no delusion that removing them will save any district a ton of money – or any for that matter.

This recommendation seems to also be tied up in the notion that we shouldn’t be paying teachers for experience or degree levels anyway. Therefore, mandating as much would clearly be foolish. I’ve addressed this idea previously in The Research Question that Wasn’t Asked.

In addition, this recommendation seems to adopt the absurd assumption that we could immediately just pay every teacher in the current system the bachelor’s degree base salary (Okay, the salary of a teacher with 3 years and a bachelor’s degree, where marginal test-score returns to experience fade). We could immediately recapture all of that salary money dumped into differentiation by experience or differentiation by degree, and that we could have massive savings with absolutely no harm to the quality of schooling – or quality of teacher labor force in the short-run or in the long-term. Again, that’s the research question that was never asked. Previous estimates of all of the money wasted on the master’s degree salary “bump” are actually this crude.

For similarly absurd analysis by Marguerite Roza regarding teacher pay, see my previous post on “inventing research findings.”

Move toward Weighted Student Funding

Petrilli and Roza also advocate moving to Weighted Student Funding. They seem to argue that the “big” savings here will come from the ability of states and school districts to immediately take back funding as student enrollments decline. That is, a district in a state, or school in a district gets a certain amount per kid. If they lose the kid, they lose the money. This keeps us from wasting a whole lot of money on kids who aren’t there anymore.

Okay… Now… most state aid is allocated on a per pupil basis to begin with. And, in general, as enrollments fluctuate, state aid fluctuates. Lose a kid. Lose the state aid that is driven by that kid. Some states have recognized that the costs of providing education don’t actually decline linearly (or increase linearly) with changes in enrollment and have included safety valves to slow the rate of aid loss as enrollments decline. Such policies are reasonable.

Petrilli and Roza seem to be belligerently and ignorantly declaring that there is simply never a legitimate reason for a funding formula to include small school district or declining enrollment provisions. I have testified in court as an expert against such provisions when those provisions are completely “out of whack”, but would never say they are entirely unwarranted. That’s just foolish, and ignorant.

Local revenues in many states (and in many districts within states) still make up a large share of public school funding, and local revenues are typically derived from property taxes applied to the total taxable property wealth of the school district. As kids come and go, local revenues do not come and go. If a tax levy of X% on the district’s assessed property values raises $8,000 per pupil – and if enrollment declines, but the total assessed value stays constant, the same tax raises more per pupil, perhaps $8,100. The district would lose state funding because it has fewer pupils (and perhaps also because it can generate larger local share per pupil). But that’s really nothing new.

There’s really no new “huge” savings to be had here.

UNLESS:

a) we are talking about kids moving to charter schools from the traditional public schools, and for each kid who moves to a charter school, we either require the district to pass along the local property tax share of funding associated with that child (Many states), or reduce state aid by the equivalent amount (Missouri).

b) there exists a property tax revenue limit tied specifically to the number of pupils served in the district (as in Wisconsin and other states) which then means that the district would have to reduce its local property taxes to generate only the per pupil revenue allowed. That’s not savings. It’s a state enforced local tax cut.

So then, why do Petrilli and Roza care about Weighted Student Funding as an option? The above two “Unless” scenarios are possible suspects. Blind reformy punditry regardless of logic is equally possible (WSF is cool… reformy… who cares what it does?).

It’s not really about “saving” money at all. Rather, it’s about creating mechanisms to enable local property tax revenues to be diverted in support of charter schools (even if the local taxpayers did not approve the charter), or to have local budgets forcibly reduced/capped when students opt-in to voucher programs (Milwaukee).

And this isn’t really a “weighted student funding” issue at all. In many states, it already works this way (WSF or not). Big savings? Perhaps an opportunity to reduce the state subsidy to charter schools by requiring greater local pass through – in those states where this doesn’t already occur. But these provisions face significant legal battles in some states. If a state is not already doing this, this policy change would also likely lead to significant up front legal expenses.

In fact, I can’t imagine a circumstance where adopting weighted student funding can be expected to either save money or improve outcomes for the same money. There’s simply no proof to this effect. Sadly, while it would seem at the very least, that adopting weighted funding might improve transparency and equity of funding across schools or districts, that’s not necessarily the case either.

My own research finds that districts adopting weighted funding formulas have not necessarily done any better than districts using other budgeting methods when it comes to targeting financial resources on the basis of student needs. See: http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/index.php/epaa/article/view/5

Petrilli and Roza’s Weighted Funding recommendation for “stretching” the dollar is strange at best. As a recommendation to state policymakers, adoption of weighted funding provides few options for “stretching” the dollar, but may provide a mechanism for diverting districts’ local revenues to support choice programs (potentially reducing state support for those programs).

As a recommendation to local school district officials, adoption of weighted funding really provides no options for “stretching” the dollar, and may, in fact, increase centralized bureaucracy required to develop and manage the complex system of decentralized budgeting that accompanies WSF (see: http://epx.sagepub.com/content/23/1/66.short)

So,

No savings?

No improvements to equity?

No evidence of improved efficiency?

What then, does WSF have to do with “stretching” the school dollar?

Baker, B.D., Elmer, D.R. (2009) The Politics of Off‐the‐Shelf School Finance Reform. Educational Policy 23 (1) 66‐105

Baker, B.D. (2009) Evaluating Marginal Costs with School Level Data: Implications for the Design of Weighted Student Allocation Formulas. Education Policy Analysis Archives 17 (3)

Savings from Small Districts and Schools

I am one who believes in creating savings through consolidation of unnecessarily small schools and school districts. And, at the school or district level, some sizeable savings can be achieved by reorganizing schools into more optimal size configurations (elementary schools of 300 to 500 students and high schools of 600 to 900 for example, See Andrews, Duncombe and Yinger)

For other research on the extent to which consolidation can help cut costs, see Does School District Consolidation Cut Costs, also by Bill Duncombe and John Yinger (the leading experts on this stuff).

Now, Petrilli and Roza, however, seem to imply that the savings from these consolidations or simply from starving the small schools and districts can perhaps help states to sustain the big districts – STRETCHING that small school dollar. Note that Petrilli and Roza ignore entirely the possibility that some of these small schools and districts (in states like Wyoming, western Kansas, Nebraska) might actually have no legitimate consolidation options. Kill them all! Get rid of those useless small schools and districts, I say!

Here’s the thing about de-funding small schools and districts to save big ones. The total amount of money often is not much… BECAUSE THEY ARE SMALL SCHOOLS!!!!! I learned this while working in Kansas, a state which arguably substantially oversubsidizes small rural school districts, creating significant inequities between those districts and some of the states large towns and cities with high concentrations of needy students. While the inequity can (and should) be reduced, the savings don’t go very far.

So, let’s say we have 6 school districts serving 100 kids each, and spending $16,000 per pupil to do so. Let’s say we can lump them all together and make them produce equal outcomes for only $10,000 per pupil. A bold, bold assumption. We just saved $6,000 per pupil (really unlikely), across 600 pupils. That’s not chump change… it’s $3,600,000 (okay… in most state budgets that is chump change).

So, now let’s take this savings, and give it to the rest of the kids in the state – oh – about 400,000. Well, we just got ourselves about $9 per pupil. Even if we try to save the mid-sized city district of 50,000 students down the road, it’s about $72 per pupil. That is something. And if we can achieve that, then fine. But slashing small districts and schools to save big, or even average ones, usually doesn’t get us very far. BECAUSE THEY ARE SMALL! GET IT! SMALL DISTRICTS WITH SMALL BUDGETS!

Similar issues apply to elimination of very small schools in large urban districts. It’s appropriate strategy – balancing and optimizing enrollment (reorganizing those too-small high schools created as a previous Gates-funded reform?). It should be done. But unless a district is a complete mess of tiny, poorly organized schools, the savings aren’t likely to go that far.

Let’s also remember that major reconfiguration of school level enrollments will require significant up front capital expense! Yep, here we are again with a significant increased expense in the short-term. Duncombe and Yinger discuss this in their work. Strangely, this slips right past Petrilli and Roza.

Use Census Based Funding for Special Education

So, what Petrilli and Roza are arguing here is that states could somehow save money by allocating their special education funding to school districts on an assumption that every school district has a constant share of its enrollment that qualifies for special education programs. Those districts that presently have more? Well, they’ve just been classifying every kid they can find so they can get that special education money. This flat-funding policy will bring them into line… and somehow “stretch” that dollar.

Let’s say we assume that every district has 16% (Pennsylvania) or 14.69% (New Jersey) children qualifying for special education. Let’s say we pick some number, like these, that is about the current average special education population. Our goal is really to reduce the money flowing to those districts that have higher than average rates. Of course, if we pick the average, we’ll be reducing money to the districts with higher rates and increasing money to the districts with lower rates and you know what – WE’LL SPEND ABOUT THE SAME IN SPECIAL EDUCATION AID? “Stretching?” how?

And will we have accomplished anything close to logical? Let’s see, we will have slammed those districts that have been supposedly over-identifying kids for decades just to get more special ed aid. That, of course, must be good.

BUT, we will also be providing aid for 14.69% of kids to districts that have only 7% or 8% children with disabilities. Funding on a census basis or flat basis requires that we provide excess special education aid to many districts – unless we fund all districts as if they have the same proportion of special education kids as the district with the fewest special education kids. That is, simply cut special education aid to all districts except the one that currently receives the least.

How is that smart “stretching?”

The only way to “save” money with this recommendation is simply to “cut funding” and “cut services.” And, unless cut to the bare minimum, the “flat allocation” strategy requires choosing to “overfund” some districts while “underfunding” others. One might try to argue that this policy change would at least reduce further growth in special ed populations. But the article below suggests that this is not likely the case either. The resulting inequities significantly offset any potential benefits.

There exist a multitude of problems with flat, or census-based special education funding, which have led to declining numbers of states moving in this direction in recent years, New Jersey being an exception. I discuss this with co-authors Matt Ramsey and Preston Green in our forthcoming chapter on special education finance in the Handbook on Special Education Policy Research.

Of course, there also exists the demographic reality that children with disabilities are simply not distributed evenly across cities, towns and rural areas within states, leading to significant inequities when using Census Based funding. CB Funding is, in fact, the antithesis of Weighted Student Funding. How does one reconcile that?

For a recent article on the problems with the underlying assumptions of Census Based special education funding, see:

Baker, B.D., Ramsey, M.J. (2010) What we don’t know can’t hurt us? Evaluating the equity consequences of the assumption of uniform distribution of needs in Census Based special education funding. Journal of Education Finance 35 (3) 245‐275

Here’s a draft copy of our forthcoming book chapter on special education finance: SEF.Baker.Green.Ramsey.Final

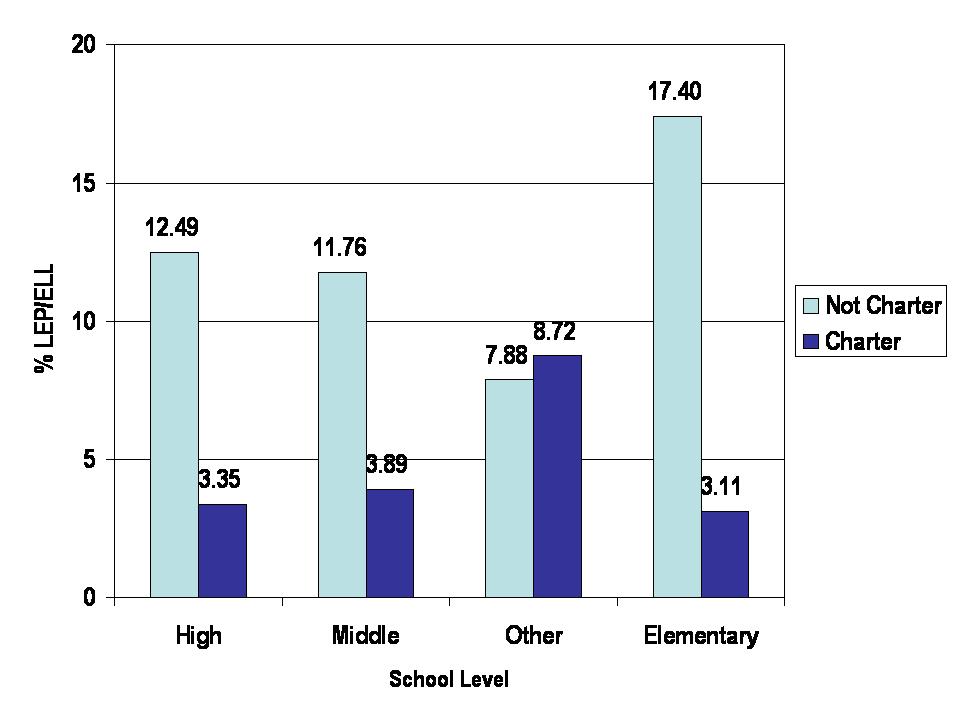

Limit Time for ELL/LEP

This one is both absurd and obnoxious. Essentially, Petrilli and Roza argue that kids should be given a time limit to become English proficient and should not be provided supplemental programs or services – or at least the money for them – beyond that time frame. For example, a child might be funded for supplemental services for 2 years, and 2 years only. Some states have done this. Again, there is no clear basis for such cutoffs, nor is it clear how one would even establish the “right” time limit, or whether that time limit would somehow vary based on the level of language proficiency at the starting time.

Yes, this approach, like cutting special education funding can be used to cut spending and cut and reduce the quality of services. But that’s all it is. It’s not “stretching” any dollar.

Other Stuff

Now, the brief does list other state policy options as well as other district practices. Some of these are rather mundane, typical ideas for “cost saving.” But, of course, no evidence or citation of actual cost effectiveness, cost benefit or cut utility analysis is presented. Petrilli and Roza toss around ideas like a) pooling health care costs, b) redesigning sick leave policies or c) shifting health care costs to employees. These are the kind of things that are often on the table anyway.

I fail to see how this new policy brief provides any useful insights in this regard. Some actual cost-benefit analysis would be the way to go. As a guide for such analyses, I recommend Henry Levin and Patrick McEwan’s book on Cost Effectiveness Analysis in Education.

There are a handful of articles available on the topic of incentives associated with varied sick leave policies, including THIS ONE, School District Leave Policies, Teacher Absenteeism, and Student Achievement, by Ron Ehrenberg of Cornell (back in 1991).

One category I might have included above is that at least two of the recommendations embedded in the report argue for stretching the school dollar, so-to-speak, by effectively taxing school employees. That is, setting up a pension system that requires greater contribution from teacher salaries, and doing the same for health care costs. This is a tax – revenue generating (or at least a give back). This is not stretching an existing dollar. This is requiring the public employees, rather than the broader pool of taxpayers (state and/or local), to pay the additional share. One could also classify it as a salary cut. But Petrilli and Roza have already proposed salary cuts in half of the other recommendations. Just say it. Hey… why not just take the “master’s bump” money and use that to pay for pensions and health care? No-one will notice it’s even gone? We all know it was wasted and un-noticed to begin with.

I was particularly intrigued by the entirely reasonable point that school districts should NOT make the harmful cuts by narrowing their curriculum. I was intrigued by this point because this is precisely what Marguerite Roza has been arguing that poor districts MUST do in order to achieve minimum standards within their existing budgets. I wrote about this issue previously HERE. It is an interesting, but welcome about-face to see Roza no-longer arguing that poor, resource constrained school districts should dump all but the basics (while other districts, with more advantaged student populations and more adequate resources need not do the same).

Utter lack of sources/evidence for any/all of this junk

Finally, I encourage you to explore the utter lack of support (or analysis) that the policy brief provides for any/all of its recommendations. It won’t take much time or effort. Read the footnotes. They are downright embarrassing, and in some cases infuriating. At the very least, they border on THINK TANKY MALPRACTICE.

There is a reference to the paper by Dan Goldhaber simulating seniority based layoffs, but that paper provides no analysis of cost/benefit, the central premise of the dollar stretching brief. The Petrilli/Roza (not Goldhaber) assumption is simply that the results will be good, and because we are firing more expensive teachers, it will cost less to get those good results.

The policy brief makes a reference to “typical teacher contracts” (FN2) regarding sick leave, with no citation… no supporting evidence, and phrased rather offensively (18 weeks a year off? For all teachers? Everywhere! OMG???)

FN2: Typical U.S. teacher contracts are for 36.5 weeks per year and include 2.5 weeks sick and personal days for a total work year of 34 weeks, or 18 weeks time off.

The brief refers to work by NCTQ (not the strongest “research” organization) for how to restructure teacher pay.

The report self-cites The Promise of Cafeteria Style Pay (by Roza, non-peer reviewed… schlock), and makes a bizarre generalized attack in footnote 5 that school districts uniformly defend the use of non-teaching staff as substitutes (no evidence/source provided).

FN5: Districts requiring non-teaching staff to serve as substitutes argue that it is good practice to have all staff in classrooms at least a few days a year.

The brief cites policy reports (and punditry) on pension gaps (including the Pew Center report), and those reports refer to alternative plans for closing gaps over time. These are important issues, but the question of how this “stretches” the school dollar is noticeably absent.

And that’s it. That’s the entire extent of “research” and “evidence” used to support this policy brief.