Note: The information below is not a comprehensive research study on the relative effectiveness of New Jersey Charter Schools. Rather, it is a quick summary of average proficiency rates for charters compared to other New Jersey schools by socio-economic strata. Unfortunately, New Jersey Charter schools were not part of two major recent multi-state analyses of charter school effectiveness, which can be found here, along with reviews & critiques of those studies. http://www.epicpolicy.org/think-tank/reviews These studies also found mixed results, with charters in some states slightly outperforming their public school counterparts, in other states performing comparably and in others performing less well. I have put together this post merely to stimulate conversation on how NJ charter schools are doing and perhaps encourage additional more thorough research.

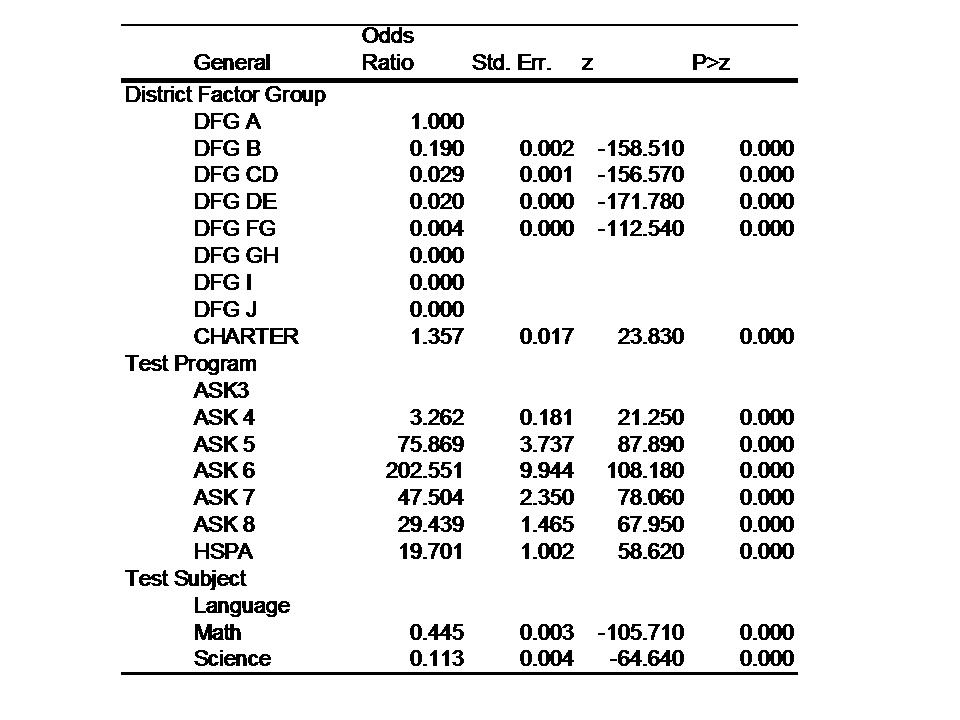

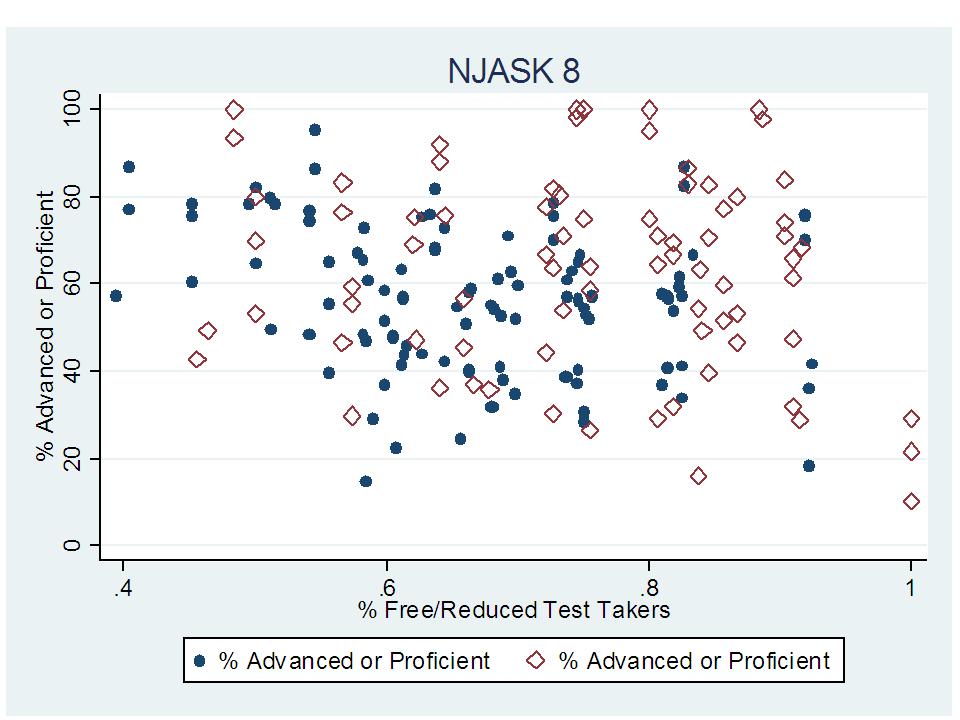

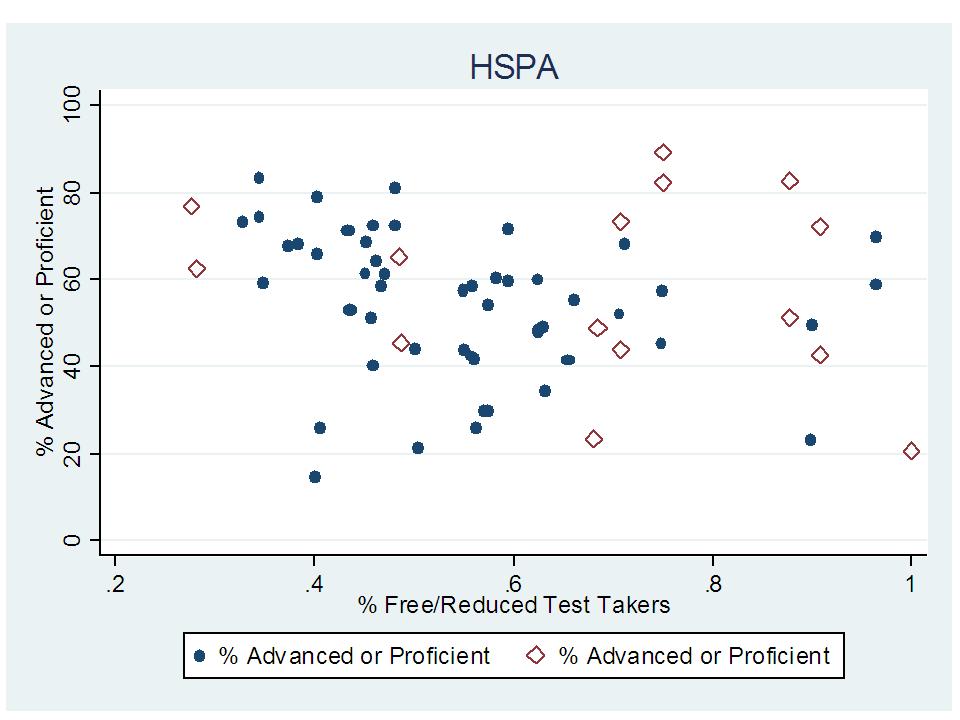

In my original post on NJ Charter School performance, Charter schools appeared to be performing somewhere between performance levels of DFG A and DFG B traditional publics. Here’s one of the graphs to that effect.

Note that the charter line – R – falls between the DFG A (poorest traditional publics) and DFG B lines. But, this analysis includes all tested students. While I expected that children with disabilties were underrepresented in Charter schools, I had no idea just how under represented until I took a look, here: https://schoolfinance101.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/charter-special-ed.jpg

For example, Robert Treat Academy has 3.8% and North Star Academy 7.8% children with disabilities in a district that has 18.1% in 2007. These are higher than many, which actually serve 0%.

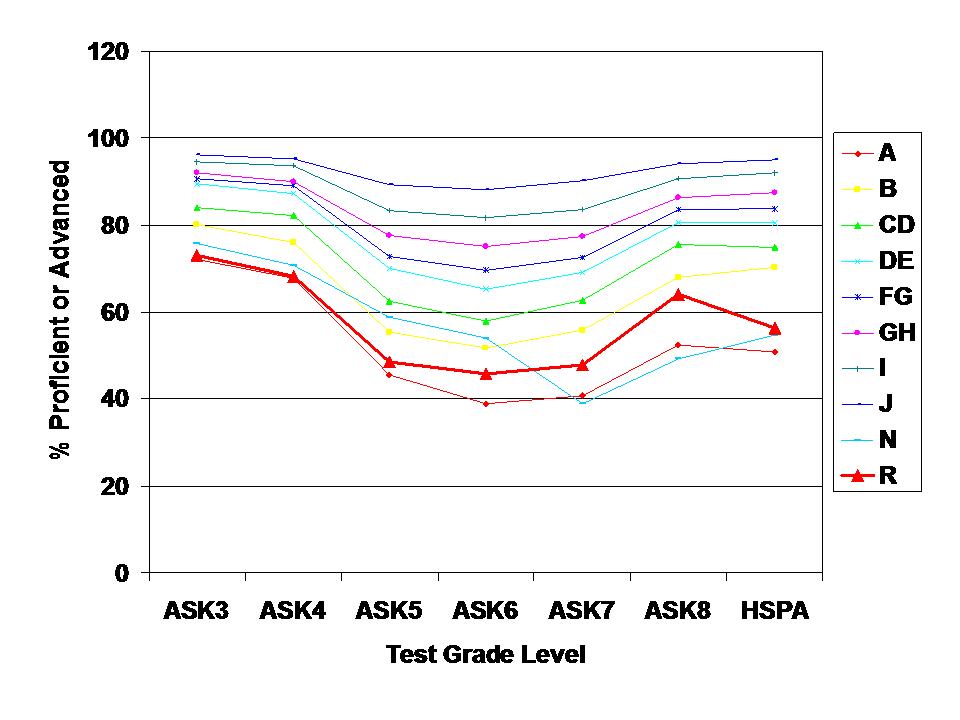

So, correcting for this problem by looking only at General Education students, the graph above becomes the graph below:

In this graph, the Charter line maps almost precisely with that of the DFG A line. That is, the slightly higher performance in the first graph is almost entirely a function of the fact that NJ Charters simply don’t serve children with disabilities and don’t have them in their test taking pool. My apologies for this apparently glaring omission.

The biggest change to my analysis however is in the relative probability that a student attends a tested grade level where less than 40% of students are proficient or higher. Making the above correction, leads to the finding that a child in a charter school is 35% more likely than a student in a DFG A traditional school to be in a tested grade level where fewer than 40% of general education students scored proficient or higher.

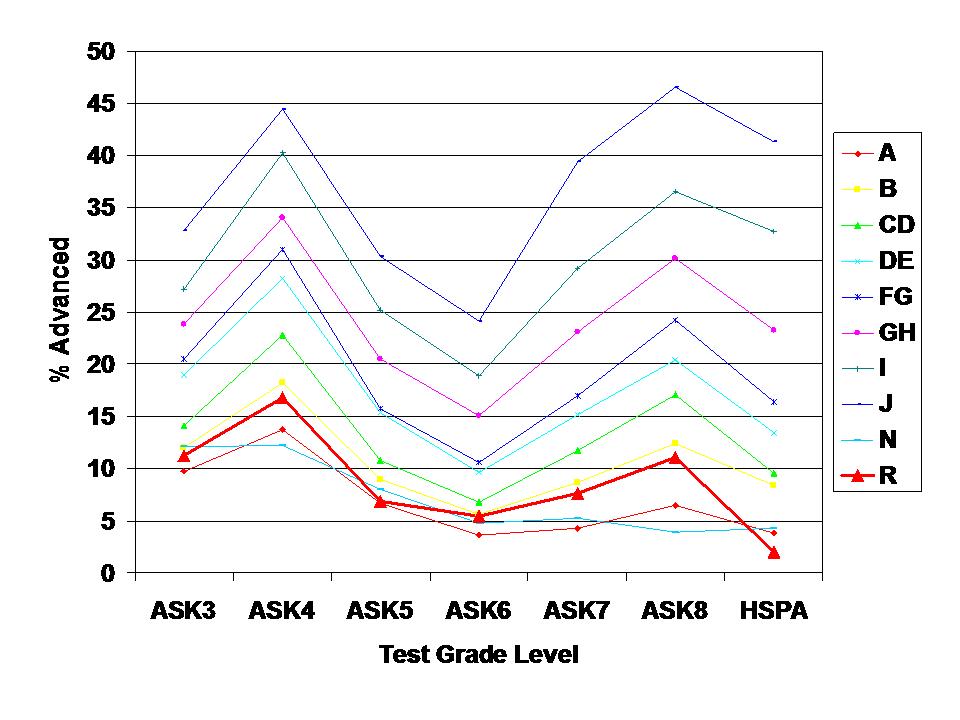

Here’s the logistic regression, weighted for number of test takers in grade level and on test (general education only), based on the 2008 report card data:

DFG A is the baseline comparison group. An odds ratio of greater than 1.0 indicates a greater likelihood of being in a grade level with fewer than 40% proficient or advanced than in a traditional DFG A school. Only charters have a greater likelihood – and much greater – 36% greater. Likelihoods vary dramatically for the different tests and subject areas. Apparently, 6th grade tests have cut scores aligned such that many more students do poorly on them. I don’t think that it’s just that 6th graders get dumb for a year. Newer tests take some tweaking. Note the dip in previous graphs. Note also that in affluent communities (GH through J), there is statistically no chance of being in a low performing grade level.

Here’s a link to the School Reports 2008 Data:

http://education.state.nj.us/rc/rc08/database/nj_rc08.xls

Please – take your own stab at this. I’ve been running these quickly. My Stata data are here.

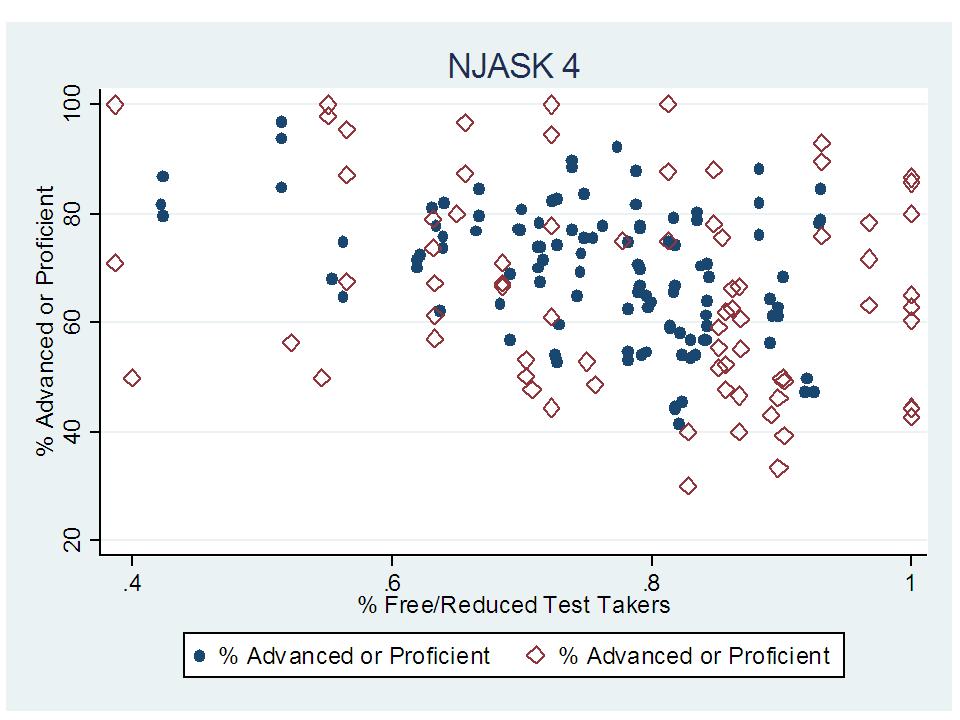

New Update: Here’s my last shot at it for now. I’ve got the odds for charters down to about 25% greater chance than DFG A schools of being in a grade level where fewer than 40% were proficient or higher. Unfortunately, poverty rates among test takers were only calculable at the district level (and for charters) not school and charters with these data (must use the enrollment data for whole school for that). Also, NJDOE continues the habit of not identifying specific locations of charters in their coding system by county. I have a bridge file somewhere, constructed by zip code, but for charters through 2006. May revisit. Anyway, here’s the logistic regression:

Ah the perils of goofing around with data too quickly/on the fly. Fun though.