In light of recent controversy over the role of state appointed “emergency” managers in Michigan, I’ve been pondering the state of taxpayer rights under the current education policy agenda(s) in New Jersey. For example:

- The state of New Jersey seems determined to maintain its control over Newark Public Schools, which, in effect, at least partially (if not almost entirely) negates the voice of local taxpayers in decisions over the operations of their schools. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/12/education/newark-school-district-in-debate-over-state-control.html

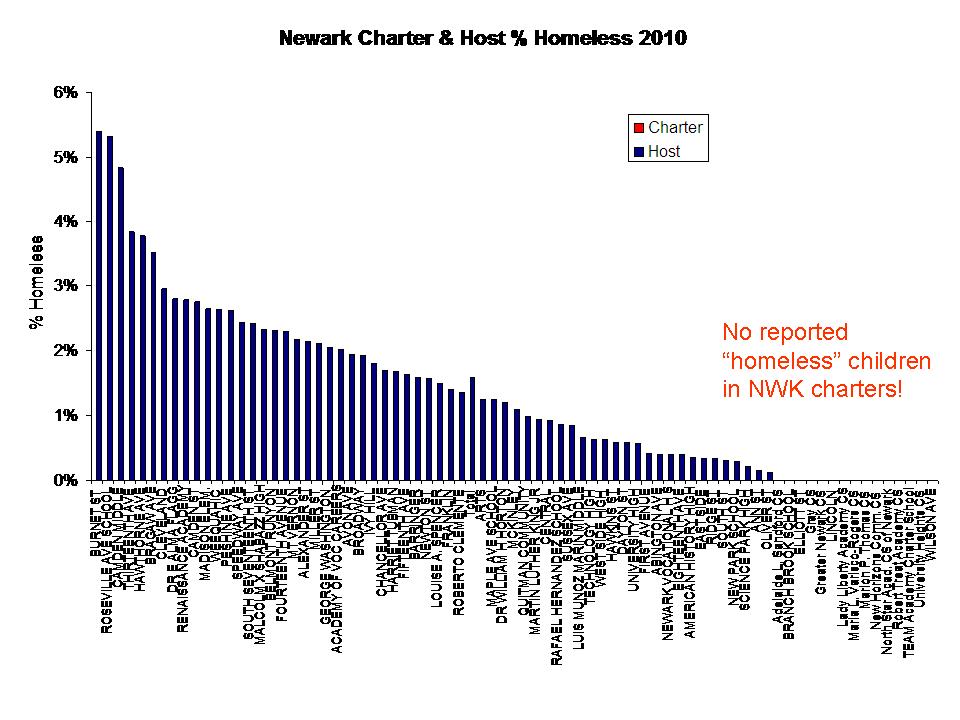

- The State of New Jersey continues to maintain a charter authorization law which permits the state department of education to grant a charter to a school to operate in any district, and draw resources from that district, including those resources derived from local property taxes. But, local taxpayers have no authority in the distribution of local tax dollars to charter schools, authorized by the state.

By contrast, in Georgia, the state constitution grants authority to establish and maintain public schools within their limits exclusively to county and area boards of education (http://www.sos.ga.gov/elections/GAConstitution.pdf, page 60). So, when the Georgia legislature approved a charter law granting authority to a state entity to approve charters (and draw on local resources), county boards of education challenged that provision in court and won.

One reasonable summary can be found here: http://www.accessnorthga.com/detail.php?n=238715, see also: http://www.earlycountynews.com/news/2011-05-18/Front_Page/Court_ruling_leaves_charter_schools_in_limbo.html

- The legislature continues to debate the adoption of a Tuition Tax Credit act, known as the Opportunity Scholarship Act. Tuition Tax Credits (or quasi-vouchers) create an indirect tax subsidy of private schooling, primarily religious private schooling in practice and in likelihood in New Jersey, by providing full tax credits to corporations to gift money to a state approved entity (voucher governing body). Thus, a hole of “X” is created in the state budget. That hole is paid for by the fact that the state no-longer has to allocate state aid (>or= X) to local public districts where students accept the scholarship to attend private schools instead. Here’s the taxpayer twist. If the state was to adopt a direct subsidy program (voucher), providing state tax dollars to religious institutions, citizen taxpayers might be able to bring a legal challenge to the use of their tax dollars on religious institutions. They might lose that challenge, as in the Cleveland voucher model which the US Supreme Court determined to be religion neutral because vouchers were provided to parents who were then able to choose religious or non-religious options, as well as to choose to take a voucher or not. So, even though nearly all private school alternatives in Cleveland were religious, the system, by its design was determined neutral. NJ taxpayers might, for example, challenge the legislative choice to include an exclusively religious community among the locations for eligibility was not religion neutral (different from Cleveland). BUT THE KICKER WITH A TUITION TAX CREDIT PROGRAM – even if it would pass constitutional muster regarding the establishment clause – IS THAT TAXPAYERS DON’T EVEN HAVE STANDING TO CHALLENGE THE CONSTITUTIONALITY IN COURT. NO TAXPAYER RIGHT AT ALL! (and we’ve been yet to figure out a party that would have standing to challenge such a model) That’s right, under this indirect subsidy approach NJ taxpayers likely would not have the right – the legal standing – to challenge NJOSA even if the legislature decided to operate the program exclusively for Lakewood? (we’d have to see how that would play out).

Do we see a theme emerging here?

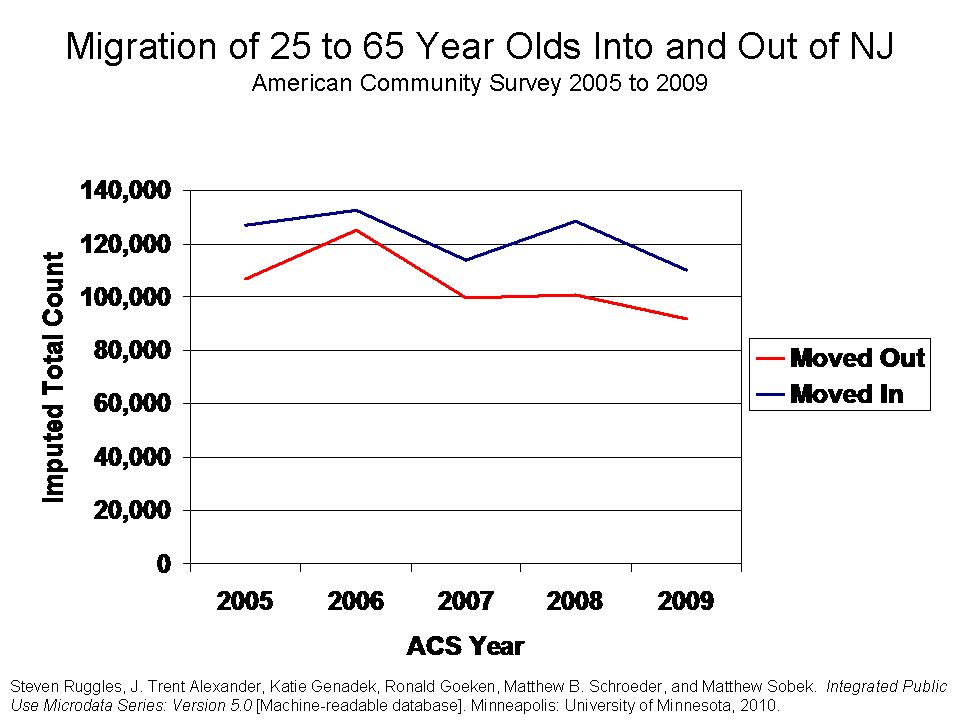

I tend to be somewhat ambivalent about deference to local control arguments. The more local we allow our education systems to be operated and financed, the greater the likelihood of substantial inequities, especially given the economically and racially segregated structure of housing stock & neighborhoods (which did not occur by chance!). Clearly, there’s a time and place for state intervention, including state intervention in local tax policy. After all, as I’ve explained previously on this blog, local tax authority often only exists as a function of state policy (often in state constitutions). Unfortunately, what I’ve realized over the years is that state governments have refined their own art of taking policies intended to improve equity (greater state financing) and have often used those policies to reinforce inequities as great as those which might exist without state intervention.

In fact, in our school funding fairness report we found absolutely no relationship between the share of revenues coming from state as opposed to local sources, and increased equity (figure 15). This is somewhat disheartening, and has me really questioning the optimal governance for achieving the appropriate balance between liberty and equity (to concepts often in tension with one another in policy design).

For now, I’m stumped, but stick by my basic assumption that an equitable distribution of sufficient levels of financial resources are necessary underlying conditions for achieving an education system that is both equitable and excellent (regardless of the balance of public-charter-private schooling in the mix). Further, I still believe that state courts (elected or appointed) have (and should use where necessary) the authority interpret equity and adequacy requirements of state constitutions pertaining specifically to education (and financing of schools), but I struggle with the best methods for managing the aftermath of those decisions. Either representative majority rule, or direct tyranny of the majority can, and does lead to policies that can only be rectified by a (quasi)independent judiciary. But I digress.

I am, at the very least, concerned at the apparent disregard for citizen/voter/taxpayer interests that seems to be emerging under New Jersey education policy.