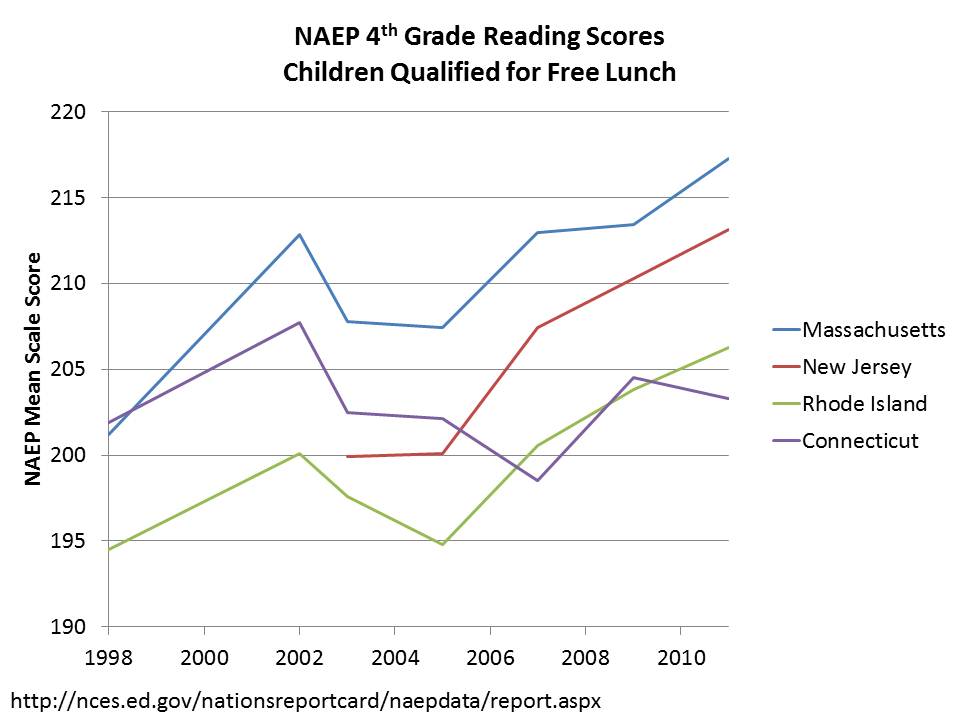

This is a brief follow up on the NJ CREDO study, which I wrote about last week when it was released. The major issues with that study were addressed in my previous post, but here, I raise an additional non-trivial issue that plagues much of our education policy research. The problems I raise today not only plague the CREDO study (largely through no real fault of their own…but they need to recognize the problem), but also plague many/most state and/or city level models of teacher and school effectiveness.

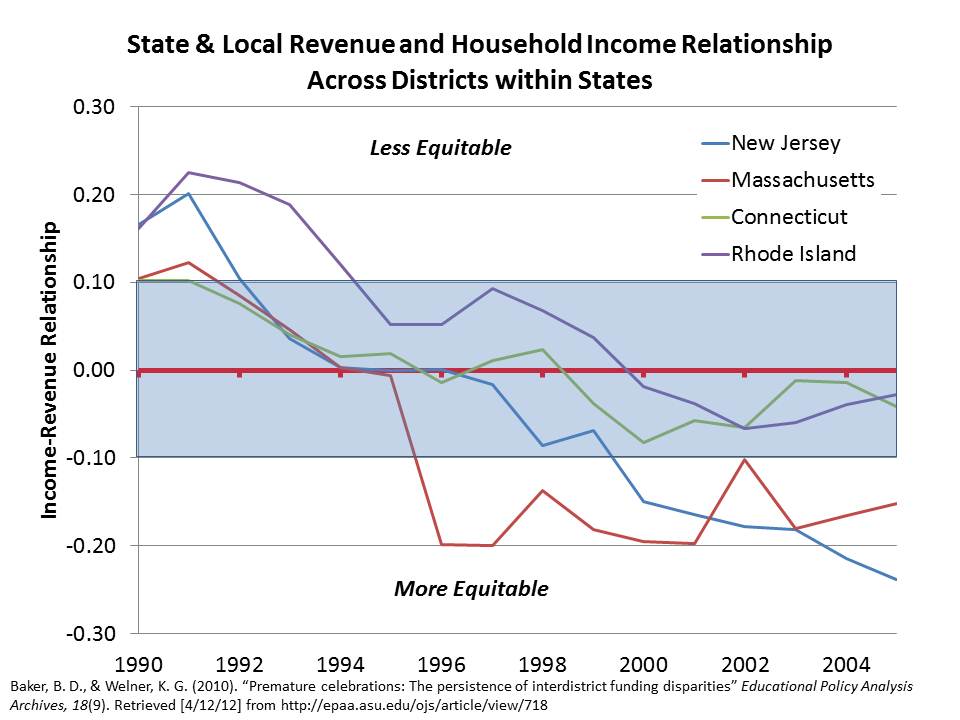

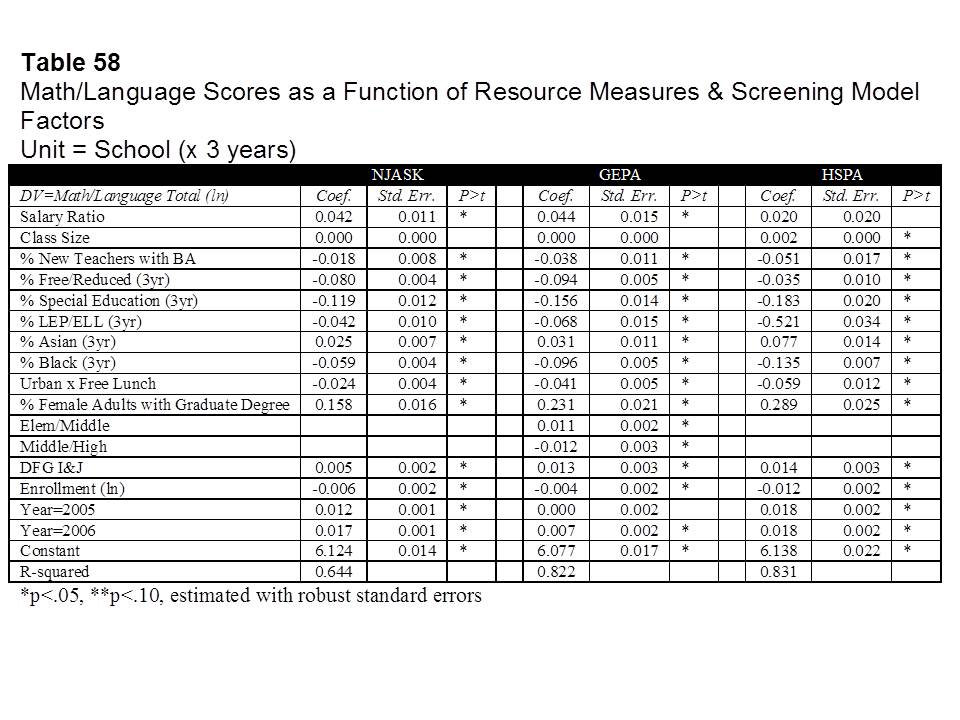

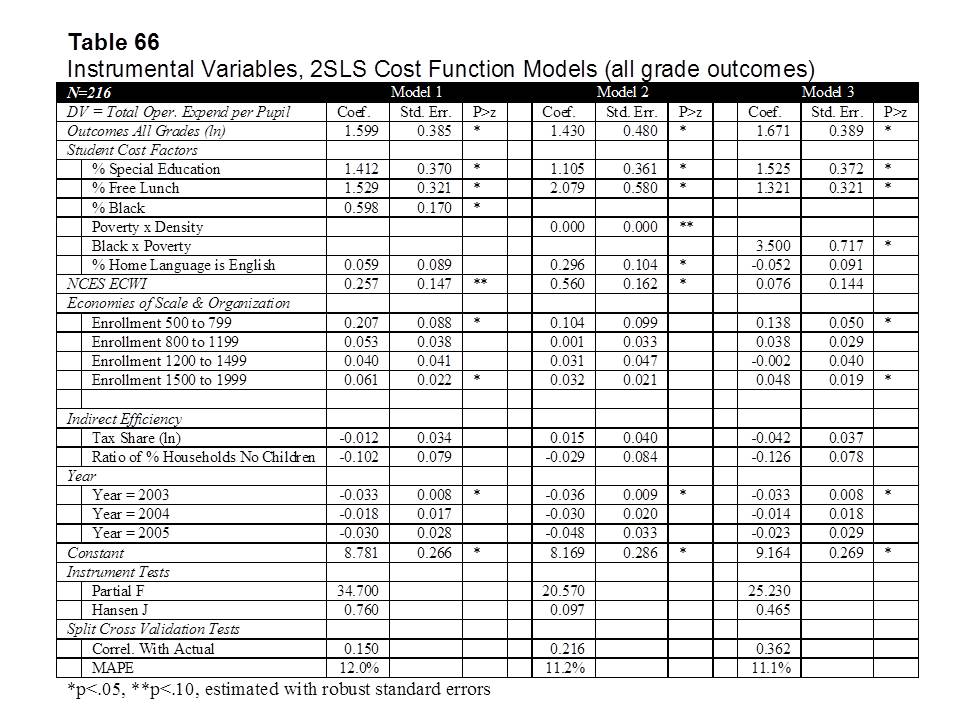

We’re all likely guilty at some point in time or another – guilty of using dummy variables that just aren’t precise enough to capture what is that we are really trying to measure. We use these variables because, well, they are available, and often, greater precision is not. But the stakes can be high if using these variables leads to misclassification/misidentification of schools for closure, teachers to be dismissed, or misidentification of supposed policy solutions deserving greater investment/expansion.

So… what is a dummy variable? Well, a dummy variable is when we classify students as Poor or Non-poor by using a simple, single income cut-off and assigning, for example, the non-poor a value 0f “0” and poor a value of “1.” Clearly, we’re losing much information when we take the entire range of income variation and lump it into two categories. And this can be consequential as I’ve discussed on numerous previous occasions. For example, we might be estimating a teacher effectiveness model and comparing teachers who each have a class loaded with 1s and few 0s. But, there’s likely a whole lot of variation across those classes full of 1s – variation between classrooms with large numbers of very low income, single parent & homeless families versus the classroom where those 1s are marginally below the income threshold.

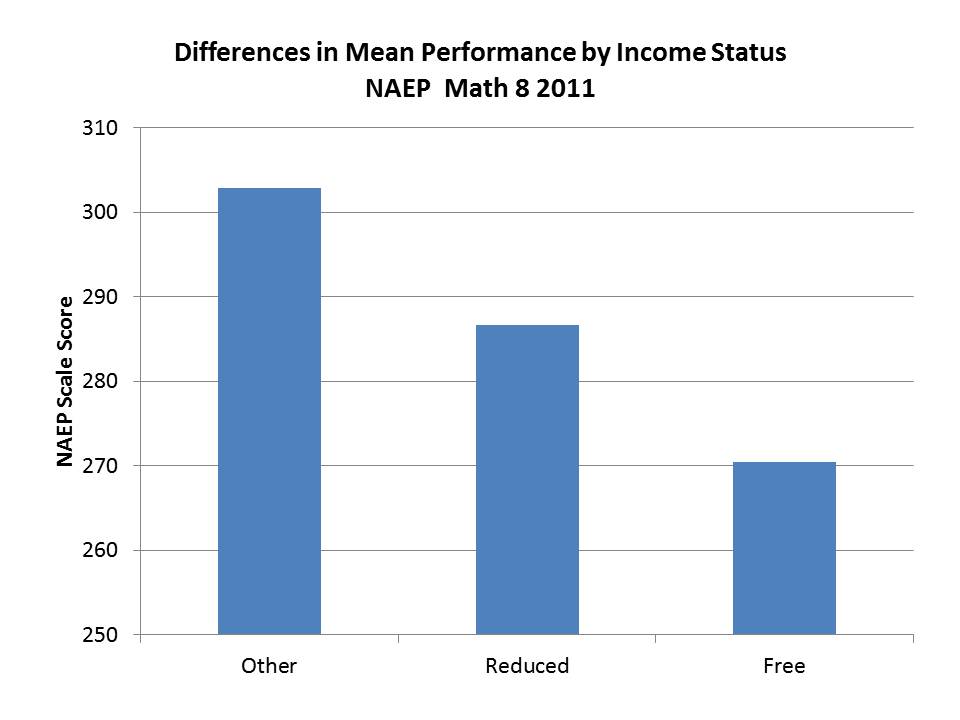

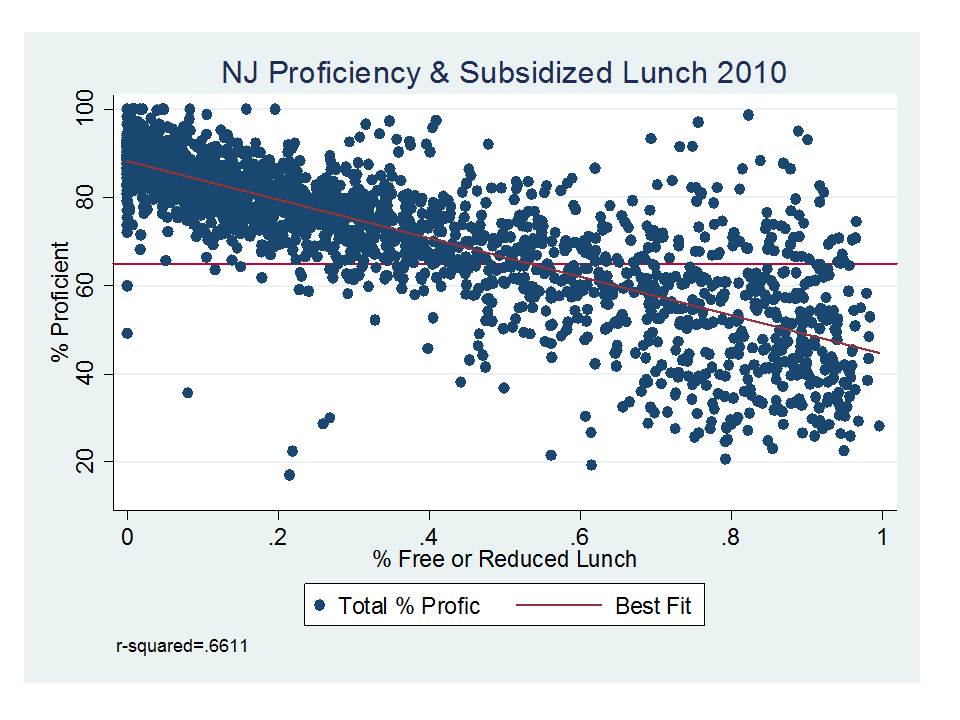

For those who’ve not really pondered this, consider that for 2011 NAEP 8th grade math performance in New Jersey, the gap between non-low income and reduced lunch kids (185% income threshold for poverty) is about the same as the gap between free (130% income level) & reduced!

The NJ CREDO charter school comparison study is just one example. CREDO’s method involves identifying matched students who attend charter schools and districts schools based on a set of dummy variables. In their NJ study, the indicators included an indicator for special education status and an indicator for children qualified for free or reduced priced lunch (as far as one can tell from the rather sketchy explanation provided). If their dummy variable matches, they are considered to be matched – empirically THE SAME. Or, as stated in the CREDO study:

…all candidates are identical to the individual charter school student on all observable characteristics, including prior academic achievement.

Technically correct – Identical on the measures used – but identical? Not likley!

The study also matched on prior test score, which does help substantially in providing additional differentiation within these ill-defined categories. But, it is important to understand that annual learning gains – as well as initial scores/starting point – are affected by a child’s family income status. Lower income, among low income, is associated with increased mobility (induced by housing instability). Quality of life during all those hours kids spend outside of school (including nutrition/health/sleep, etc.) affect childrens’ ability to fully engage in their homework and also likely affect summer learning/learning loss (access to summer opportunities varies by income/parental involvement, etc.). So – NO – it’s not enough to only control for prior scores. Continued deprivation influences continued performance and performance growth. As such, this statement in the CREDO report is quite a stretch (but is typical, boilerplate language for such a study):

The use of prior academic achievement as a match factor encompasses all the unobservable characteristics of the student, such as true socioeconomic status, family background, motivation, and prior schooling.

Prior scores DO NOT capture persistent differences in unobservables that affect the ongoing conditions under which children live, which clearly affect their learning growth!

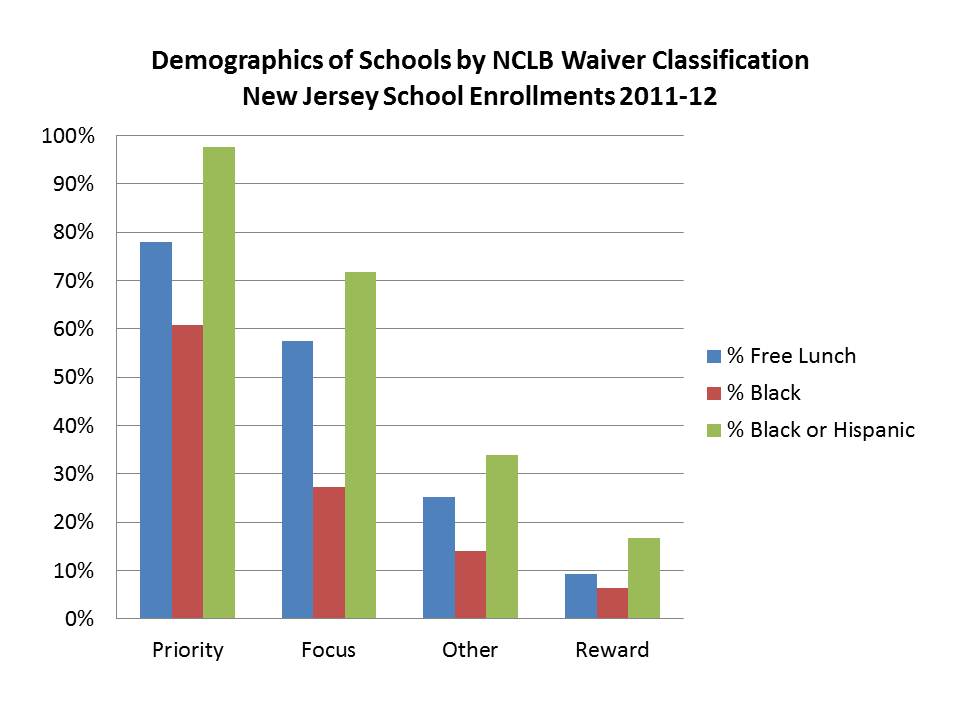

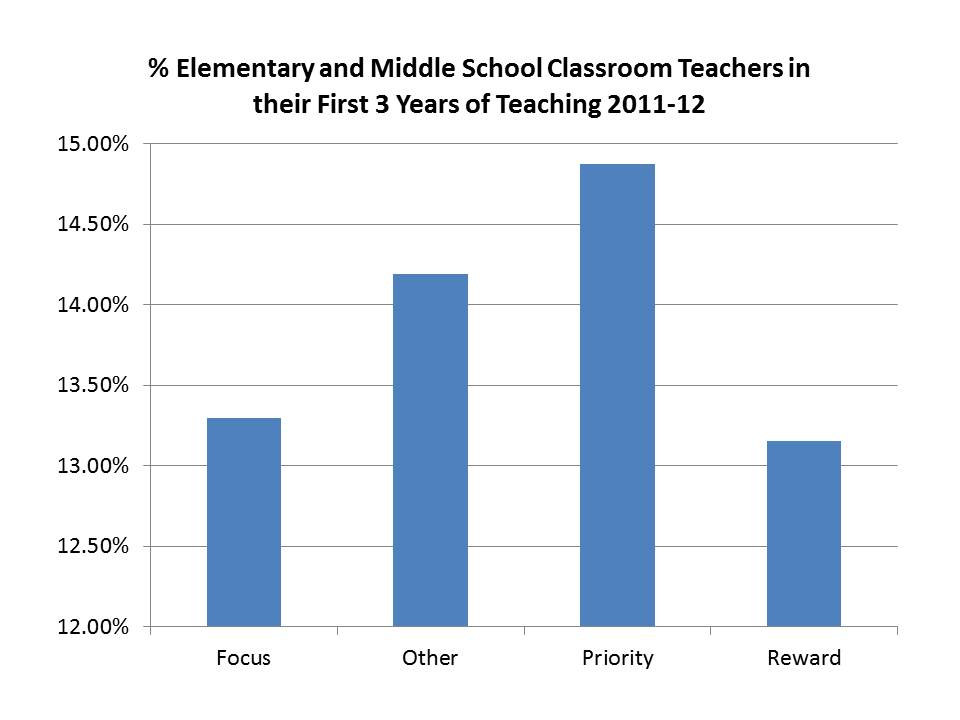

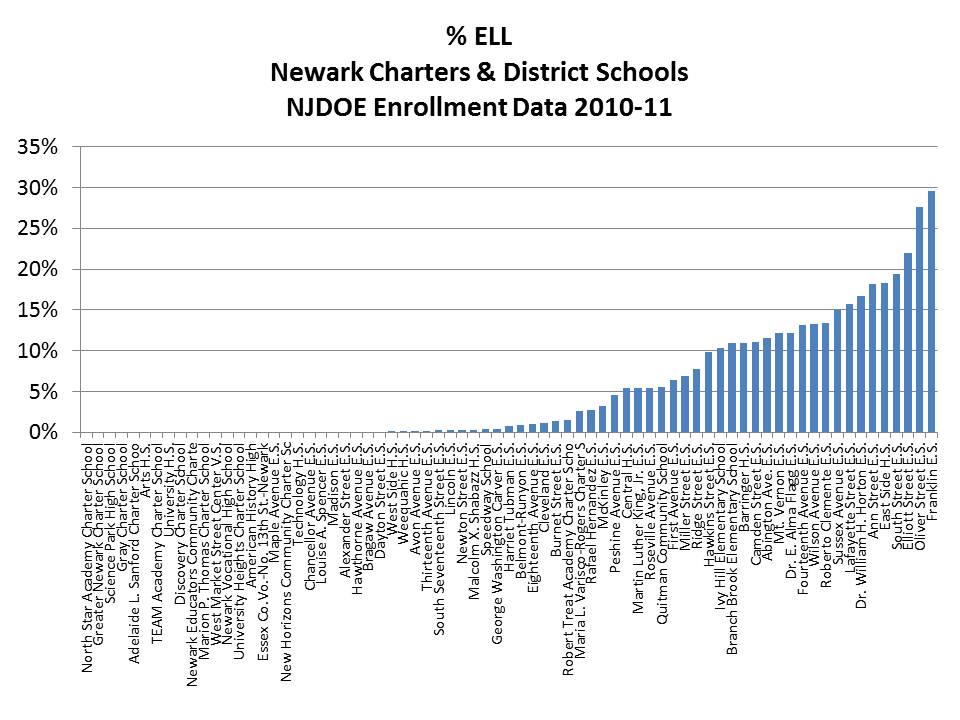

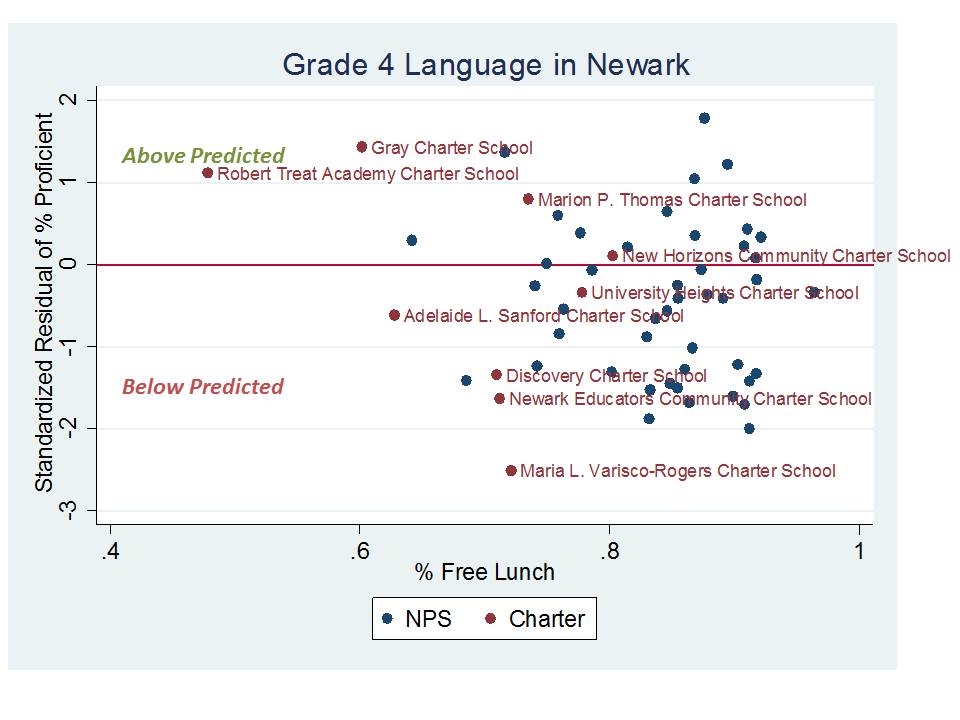

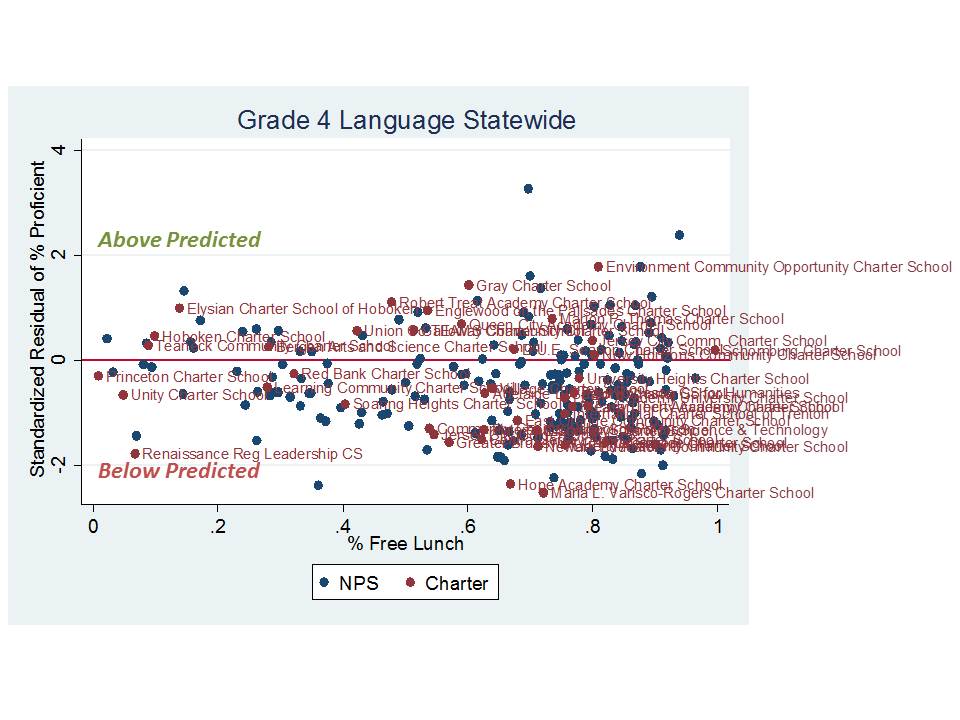

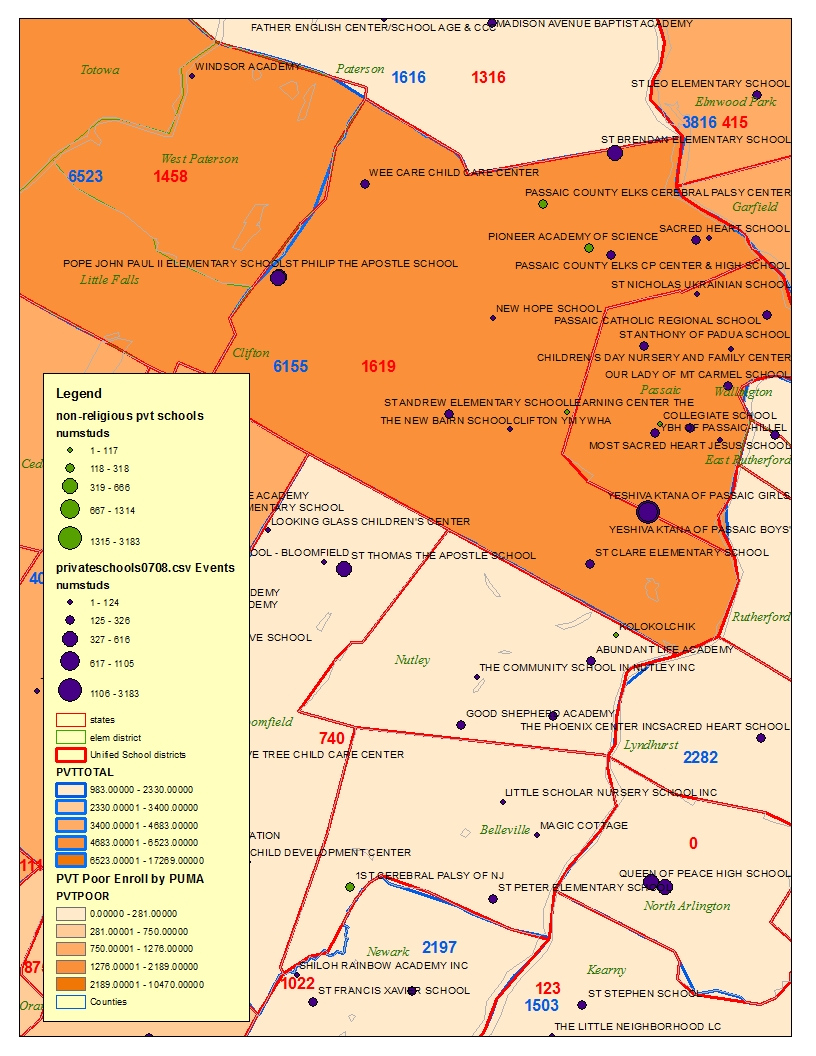

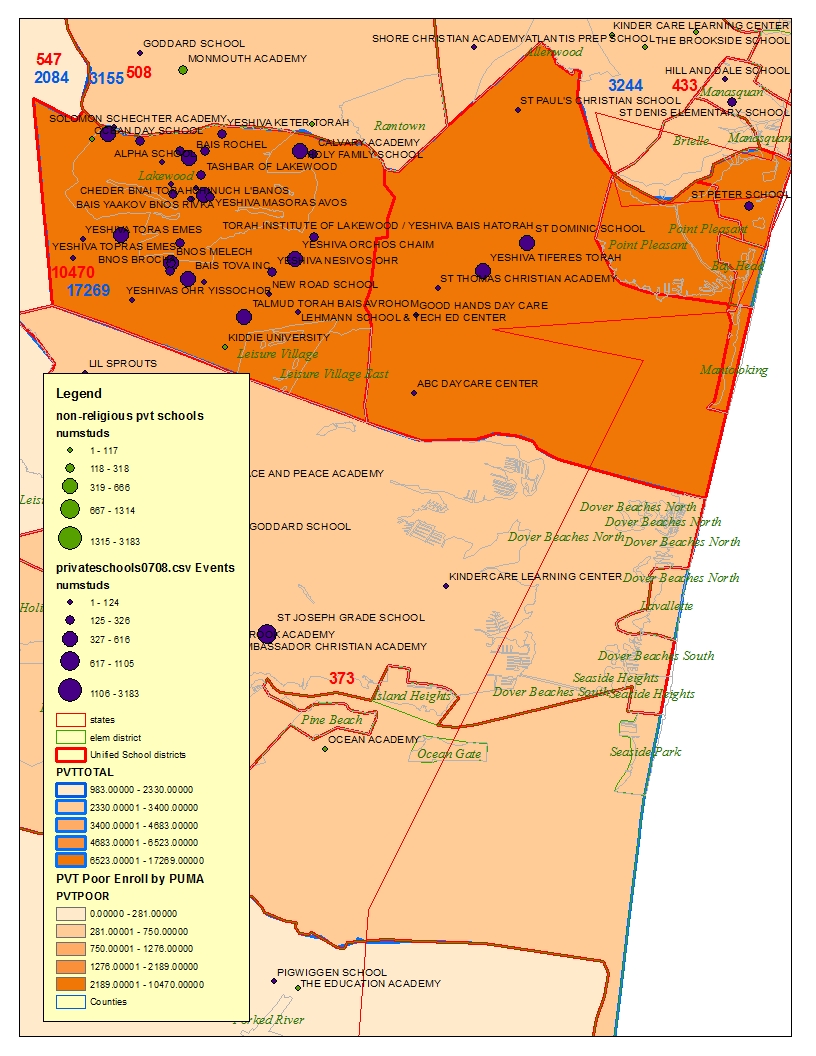

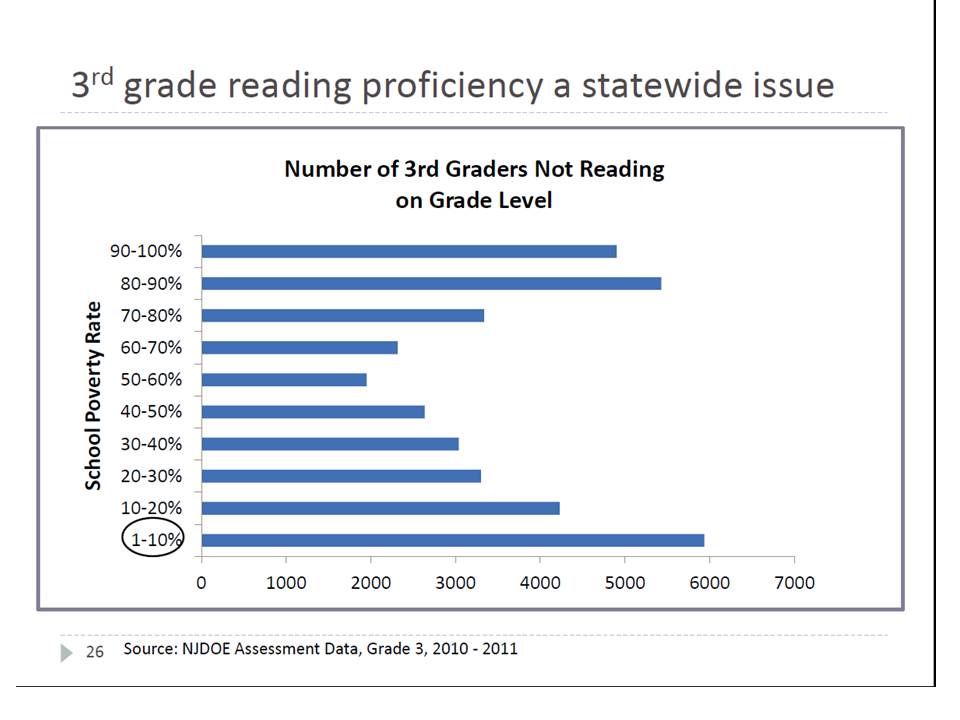

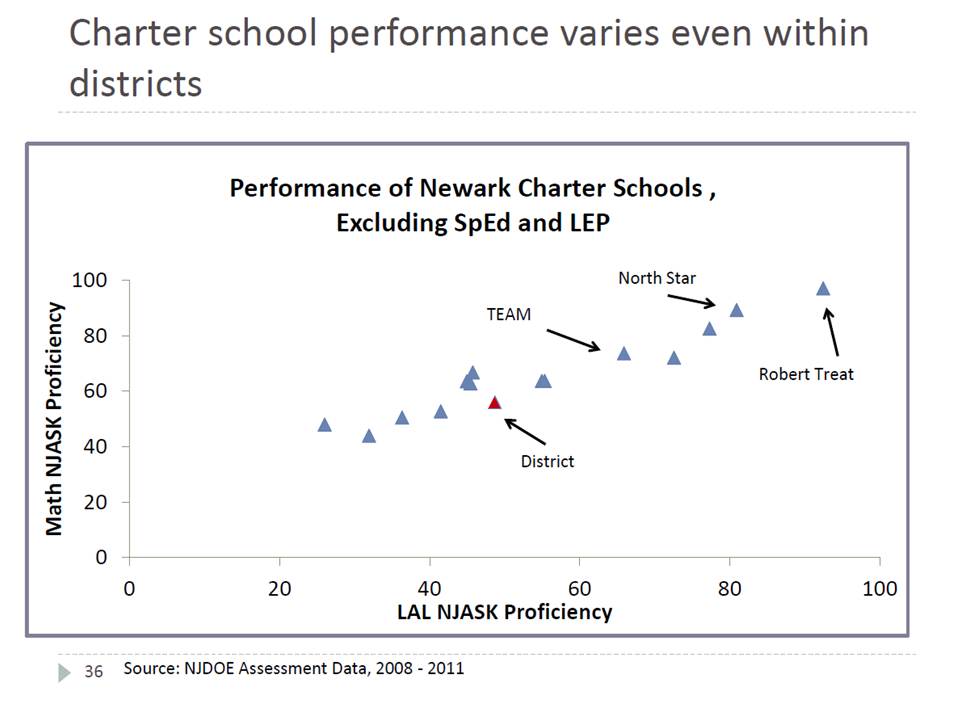

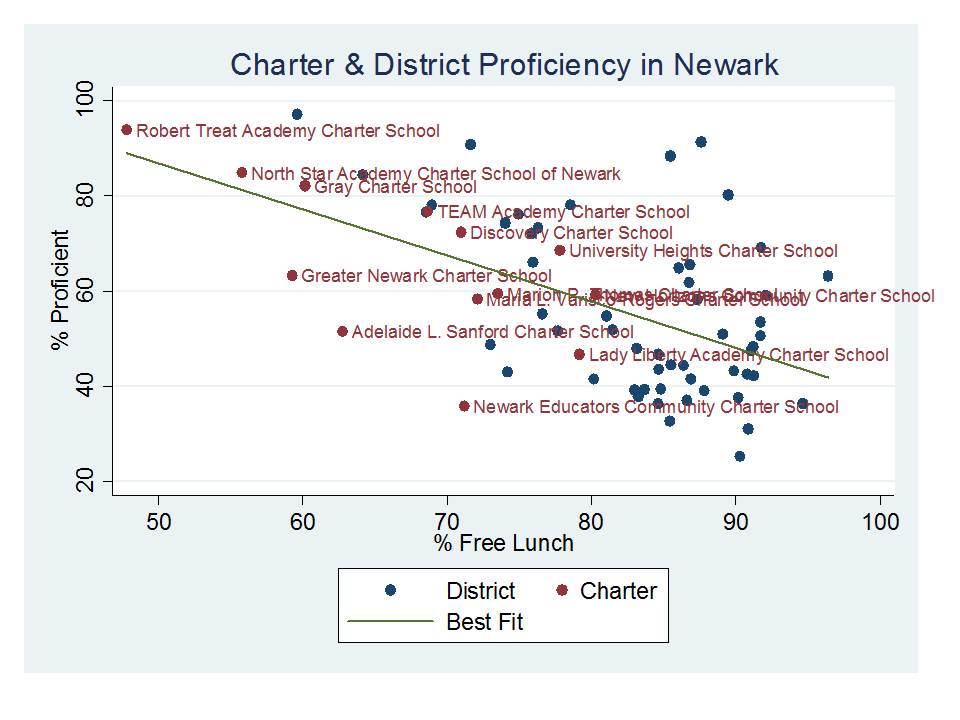

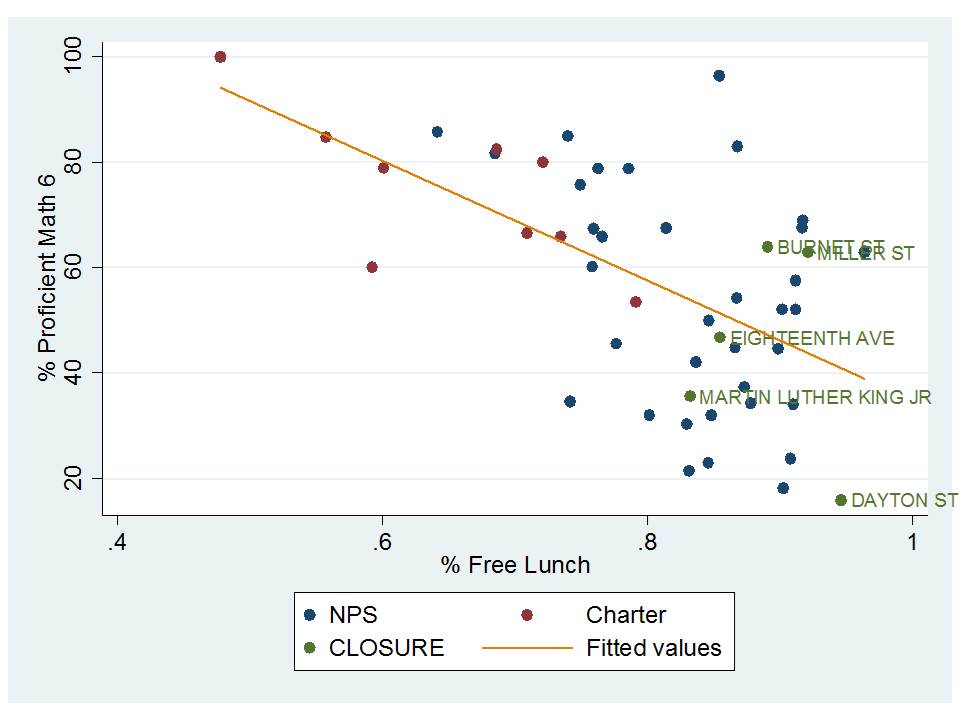

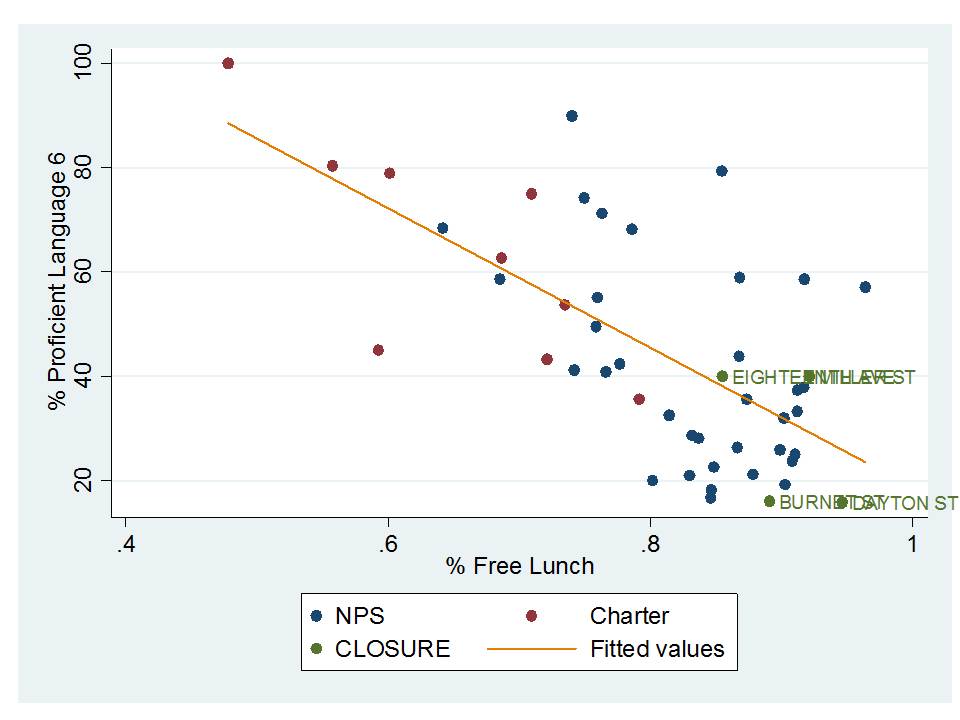

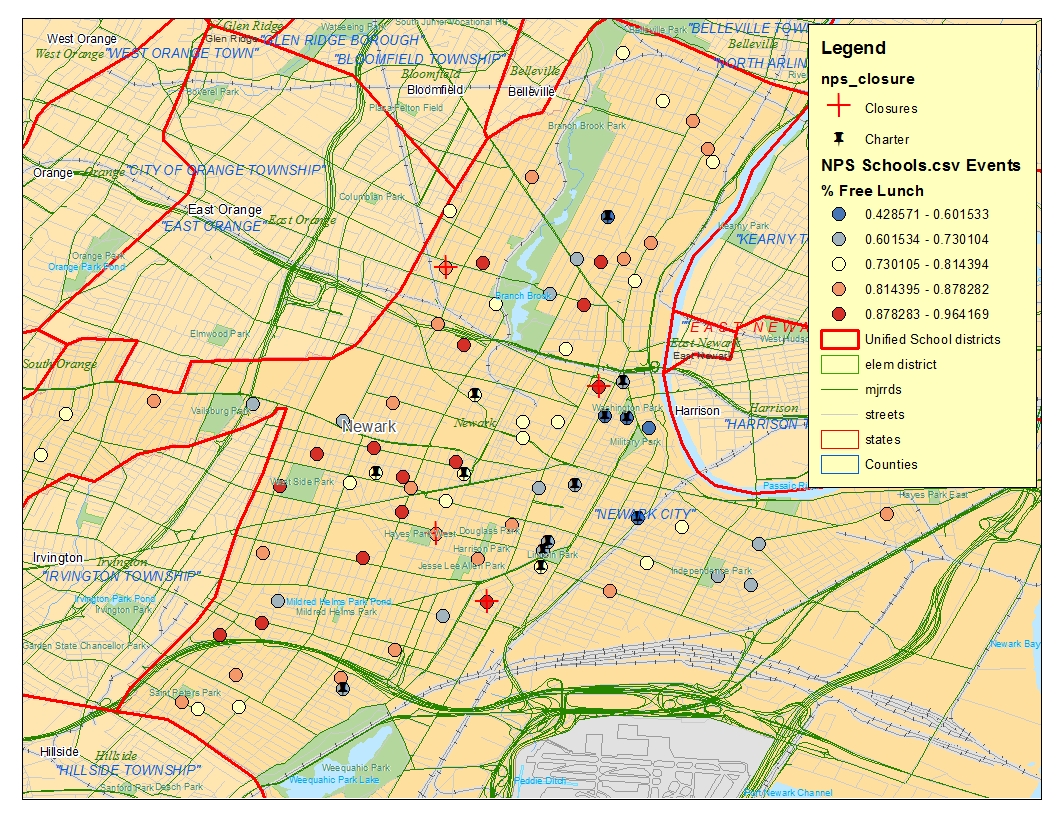

Now, one problem with the CREDO study is that we really don’t know which schools are involved in the study, so I’m unable here to compare the demographics of the schools actually included among charters with district schools. But, for illustrative purposes, here are a few figures that raise significant questions about the usefulness of matching charter students and district students on the basis of “special education” as a single indicator, and “free AND reduced” lunch qualification as a single indicator.

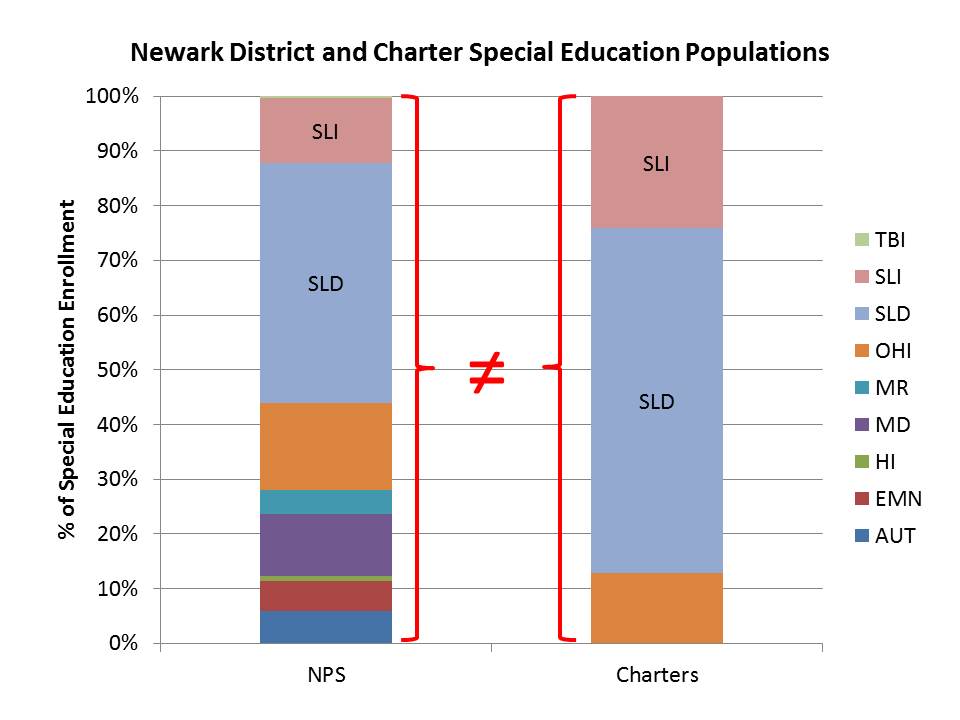

First, here are the characteristics of special education populations in Newark district and charter schools.

As I noted in my previous post, nearly all special education students in Newark Charter schools have mild specific learning disabilities and the bulk of the rest have speech impairment. Yet, students in districts schools who may have received the same dummy variable coding are far more likely to have multiple disabilities, mental retardation, emotional disturbance, etc. It seems rather insufficient to code these groups with a single dummy variable… even if the classifications of the test-taker population were more similar than those of the total enrolled population (assuming many of the most severely disabled children were not in that test-taker sample?).

As I noted in my previous post, nearly all special education students in Newark Charter schools have mild specific learning disabilities and the bulk of the rest have speech impairment. Yet, students in districts schools who may have received the same dummy variable coding are far more likely to have multiple disabilities, mental retardation, emotional disturbance, etc. It seems rather insufficient to code these groups with a single dummy variable… even if the classifications of the test-taker population were more similar than those of the total enrolled population (assuming many of the most severely disabled children were not in that test-taker sample?).

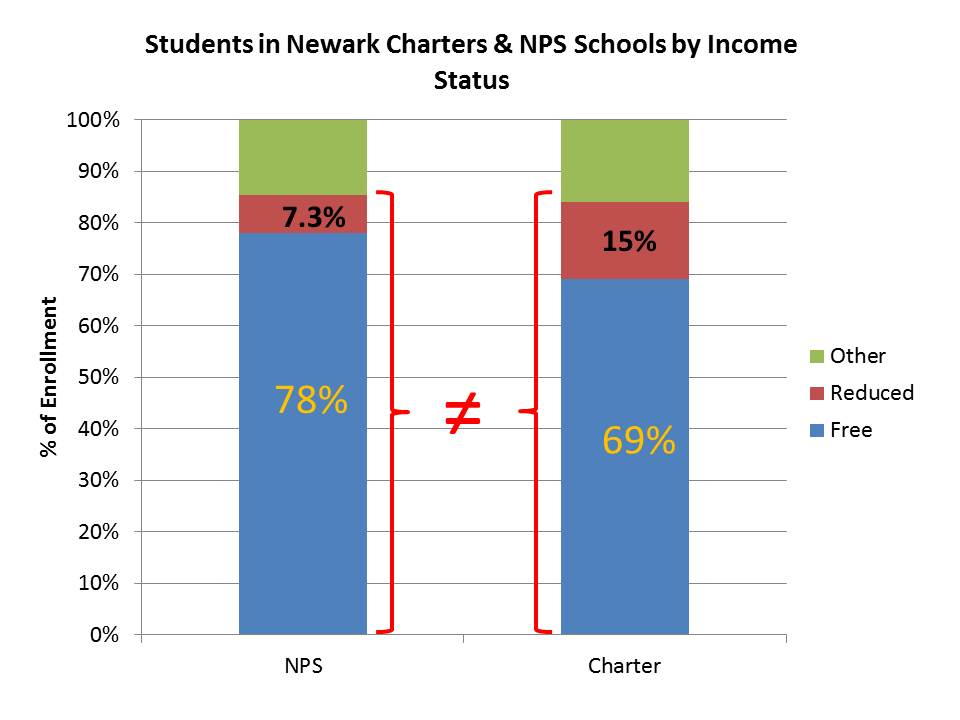

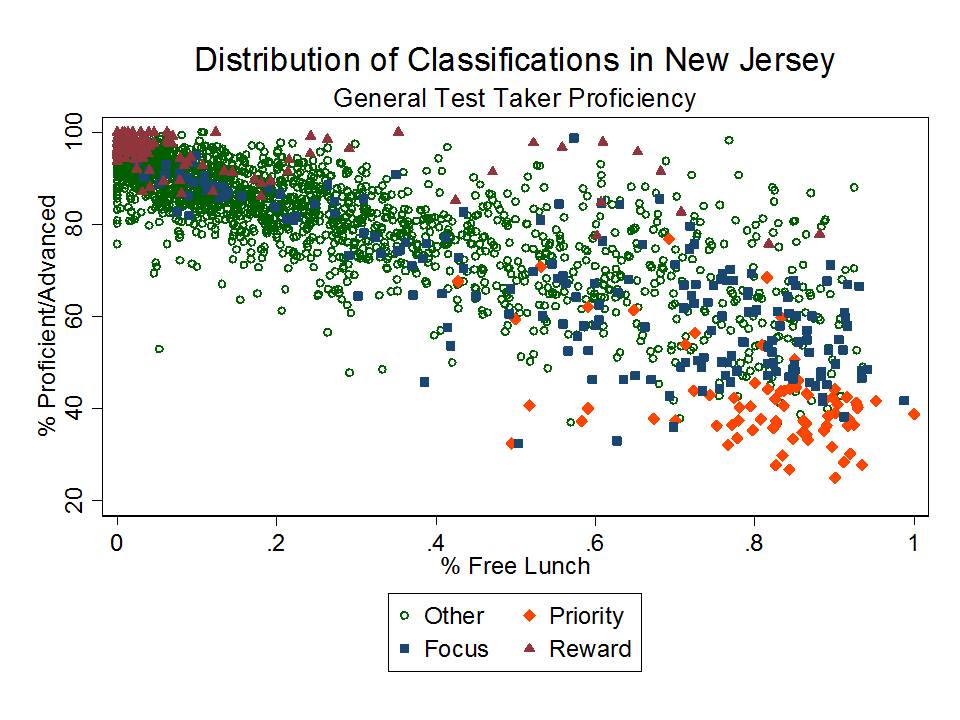

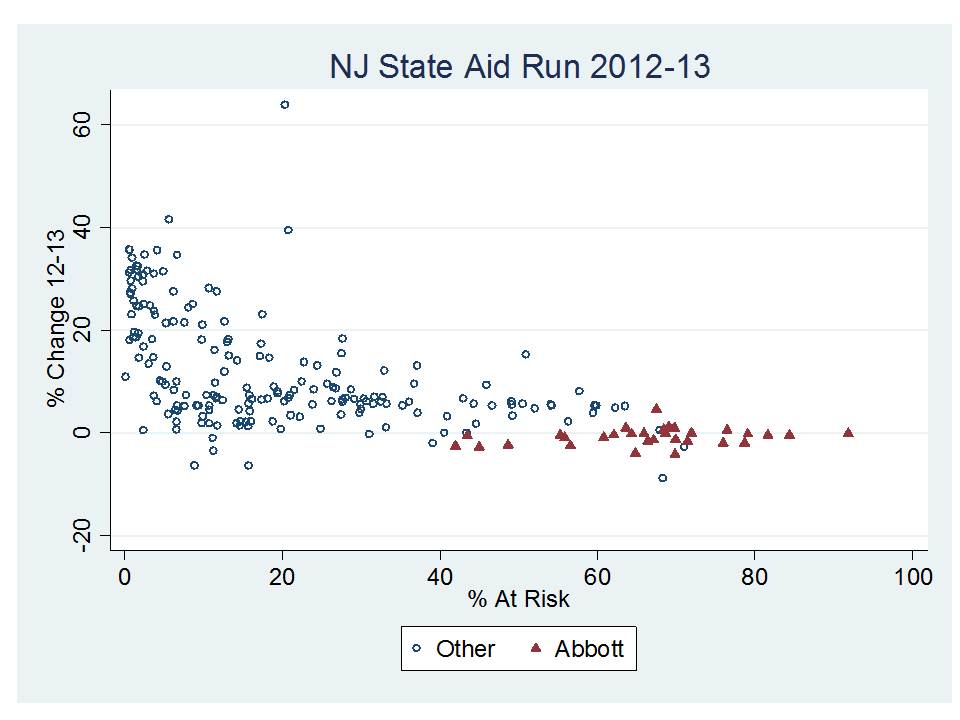

Now, here are the variations by income status – first for district and charter schools in the aggregate:

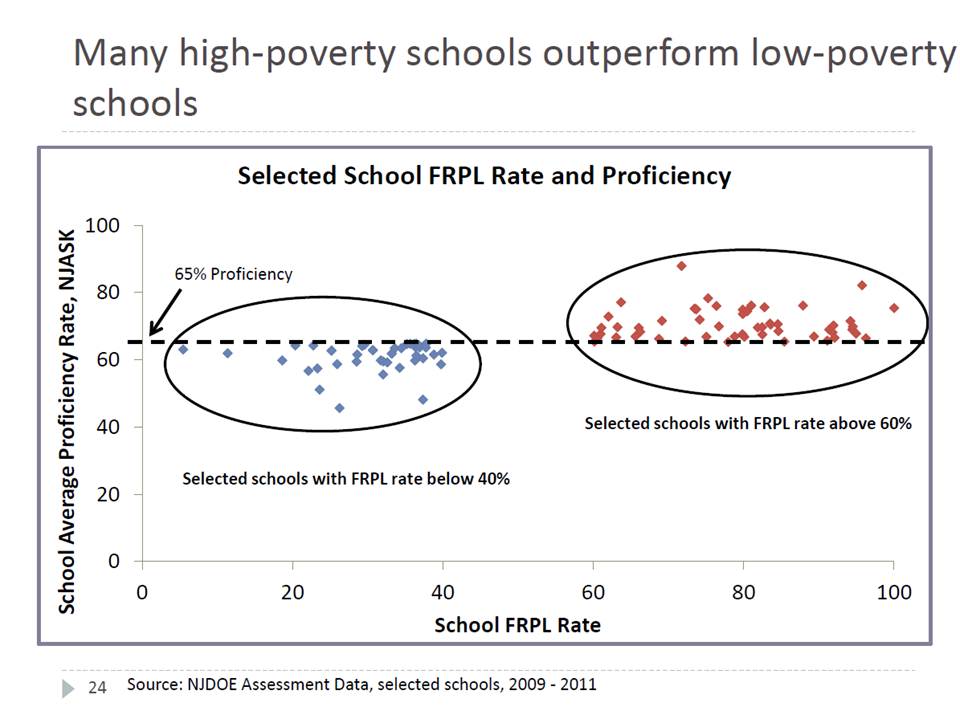

Here, charters in Newark as I’ve noted previously, generally have fewer low income students, but they have far fewer students below the 130% income threshold than they do between the 130% and 185% thresholds. It would be particularly interesting to be able to parse the blue regions even further as I suspect that charters serve an even smaller share of those below the 100% threshold. Using a single dummy variable, any child in either the red or blue region was assigned a 1 and assumed to be the same (excuse me… “IDENTICAL?”). But, as it turns out, there is about twice the likelihood that the child with a 1 in a charter school was in a family between the 130% and 185% income thresholds. And that may matter quite a bit, as would additional differences within the blue region.

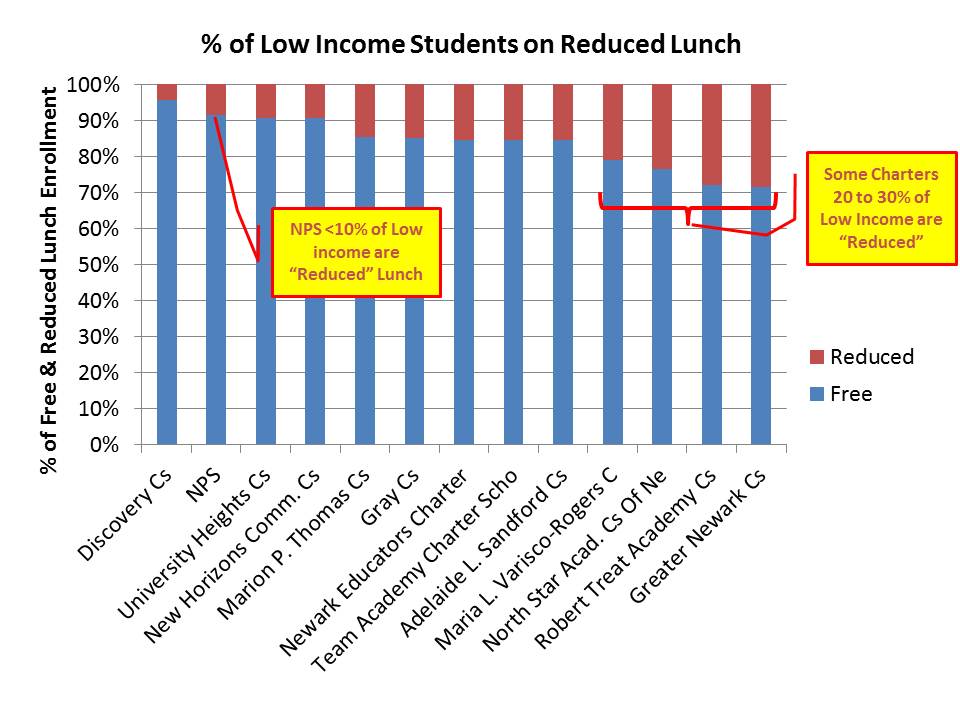

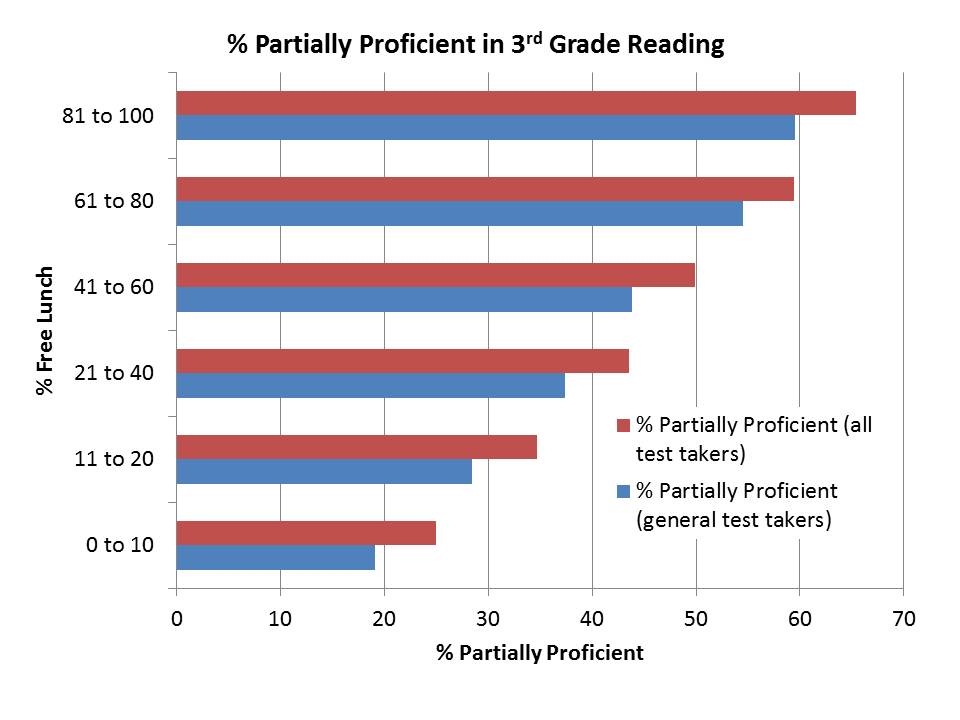

Here’s the distribution of free vs. reduced price lunch across NJ charter schools – among their free/reduced populations.

While less than 10% of the free/reduced population in NPS is in the upper income bracket, a handful of Newark Charter schools – including high flyers like Greater Newark, Robert Treat and North Star, have 20% to 30% of their (relatively small) low income populations in the upper bracket of low income. That is, for the “matched child” who attended Treat, North Star or Greater Newark there was a 2 to 3 times greater chance than for the their “peer” in NPS that they were from the higher (low) income group.

Again… CREDO likely worked with the data they have. However, I do find inexcusable the repeated sloppy use of the term “poverty” to refer to children qualified for free or reduced price lunch, and the failure of the CREDO report to a) address any caveats regarding their use of these measures or b) provide any useful comparisons of the differences in overall demographic context between charter schools and district schools.