For a short while yesterday – more than I would have liked to – I followed the circus of testimony and tweets about proposed education reform legislation in Connecticut. The reform legislation – SB 24 – includes the usual reformy elements of teacher tenure reform, ending seniority preferences, expanding and promoting charter schooling, etc. etc. etc. And the reformy circus had twitpics of of eager undergrads (SFER) & charter school students (as young as Kindergarten?) shipped in and carrying signs saying CHARTER=PUBLIC (despite a body of case law to the contrary, and repeated arguments, some lost in state courts [oh], by charter operators that they need not comply with open records/meetings laws or disclose employee contracts), and tweeting reformy platitudes and links to stuff they called research supporting the reformy platform (Much of it tweeted as “fact checking” by the ever-so-credible ConnCAN).

Ignored in all of this theatre-of-the-absurd was any actual substantive, knowledgeable conversation about the state of public education in Connecticut, the nature of the CT achievement gap and the more likely causes of it, and other problems/failures of Connecticut education policy.

First, that achievement gap:

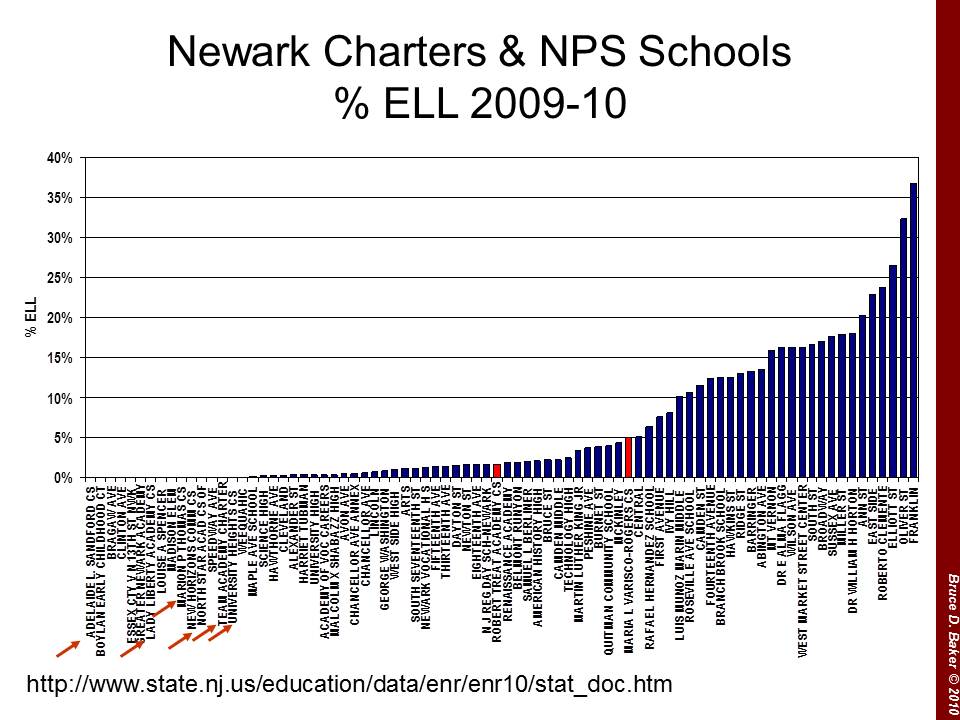

Yes, Connecticut has a large achievement gap… among the largest. But, I encourage you to read my previous post in which I explain that poverty achievement gaps in states tend to be mostly a function of income disparity in states. The bigger the income difference between rich and poor, the bigger the achievement gaps between them. But, even then, the CT achievement gap is a problem. CT’s income gaps between poor and non-poor are most similar to those of MA and NJ, but both MA and NJ do better than CT on achievement gap measures. Here’s a graph relating income gap and achievement gap:

Connecticut has a higher than otherwise expected gap and MA, NJ and RI have lower.

Connecticut has a higher than otherwise expected gap and MA, NJ and RI have lower.

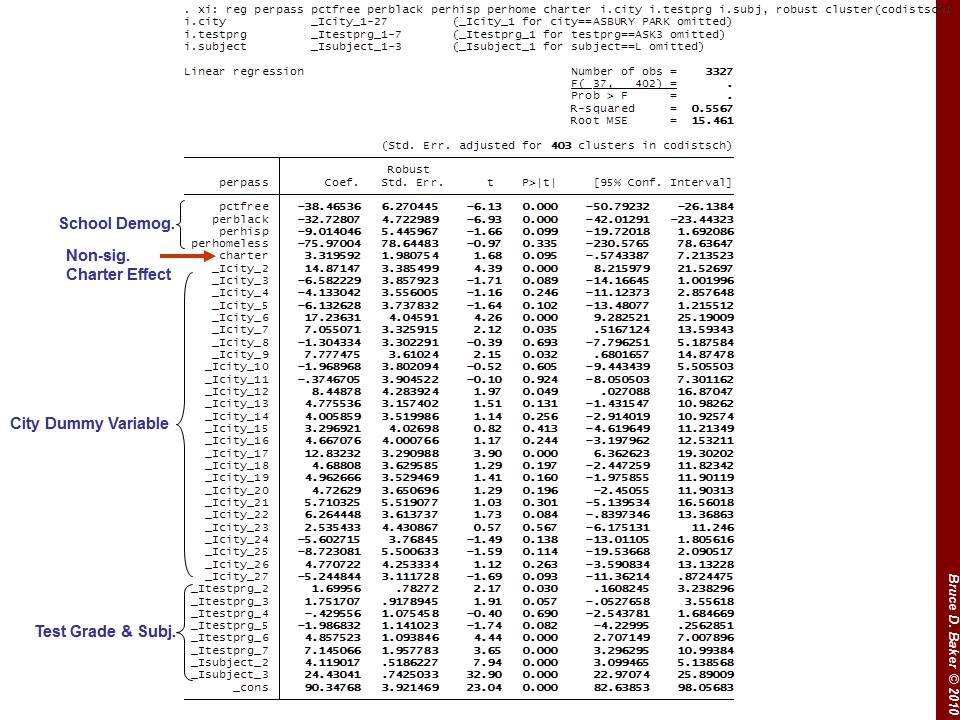

But, is this because of teacher tenure? Is it because teachers aren’t regularly fired because of bad student test scores? Is it because there aren’t enough charter or magnet schools in CT? That’s highly unlikely for several reasons.

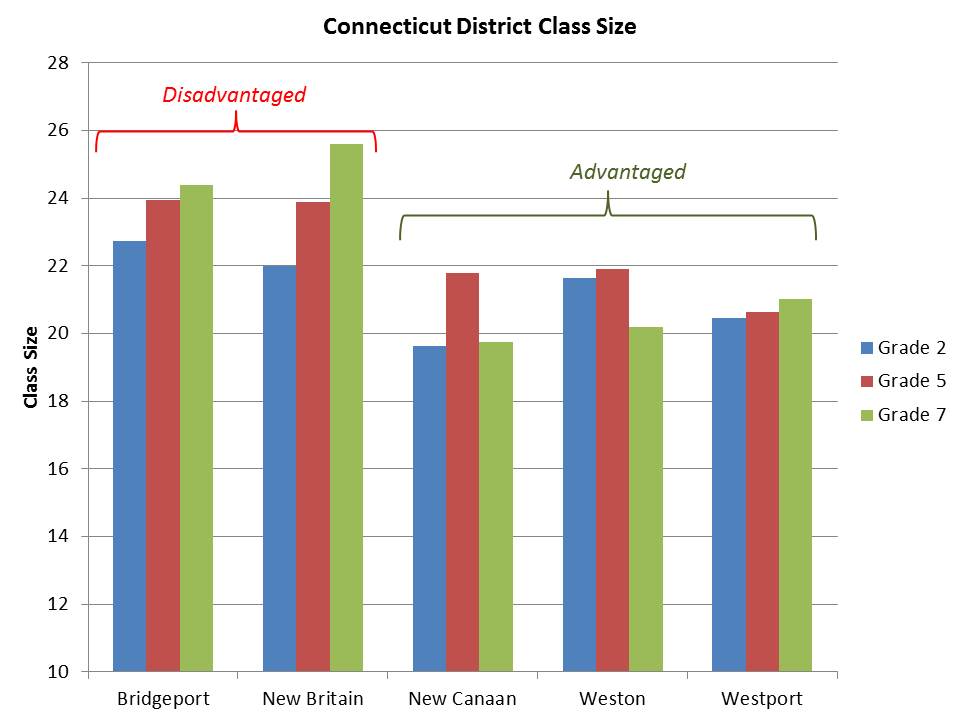

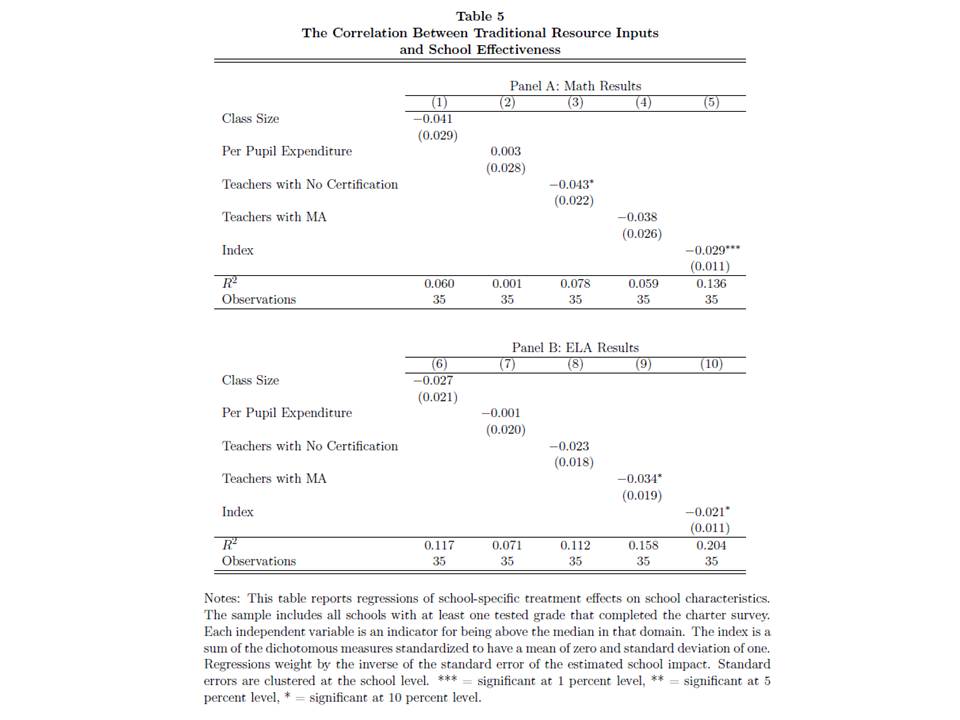

First, teachers have tenure status in both higher and lower performing, higher and lower income districts in CT. As I show below, teacher salaries are lower and class sizes larger in disadvantaged districts. SB24 does NOTHING to fix that.

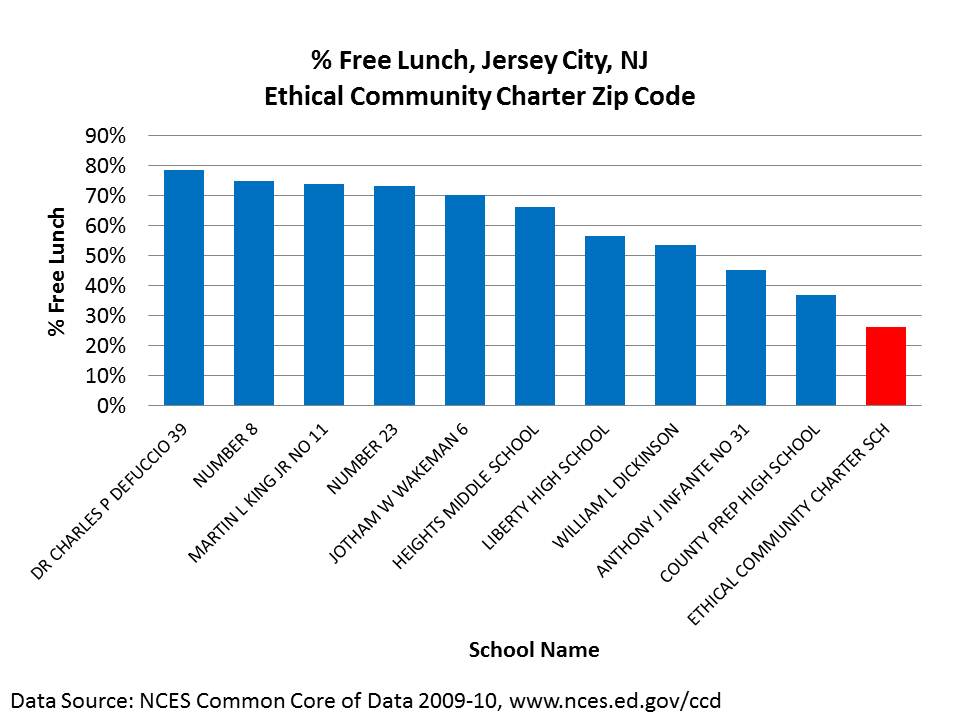

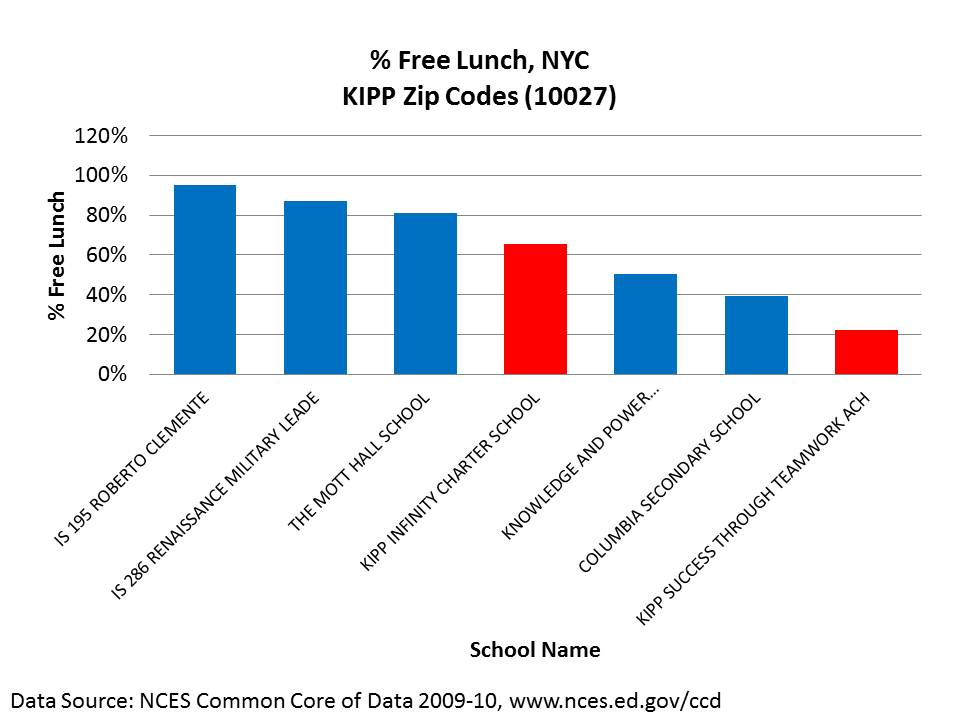

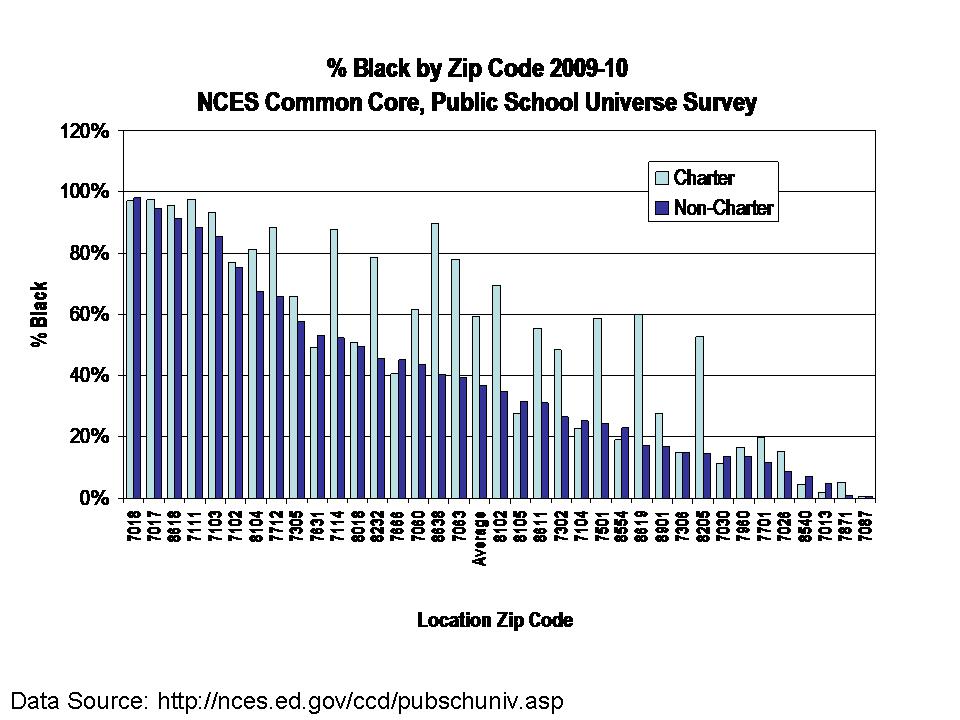

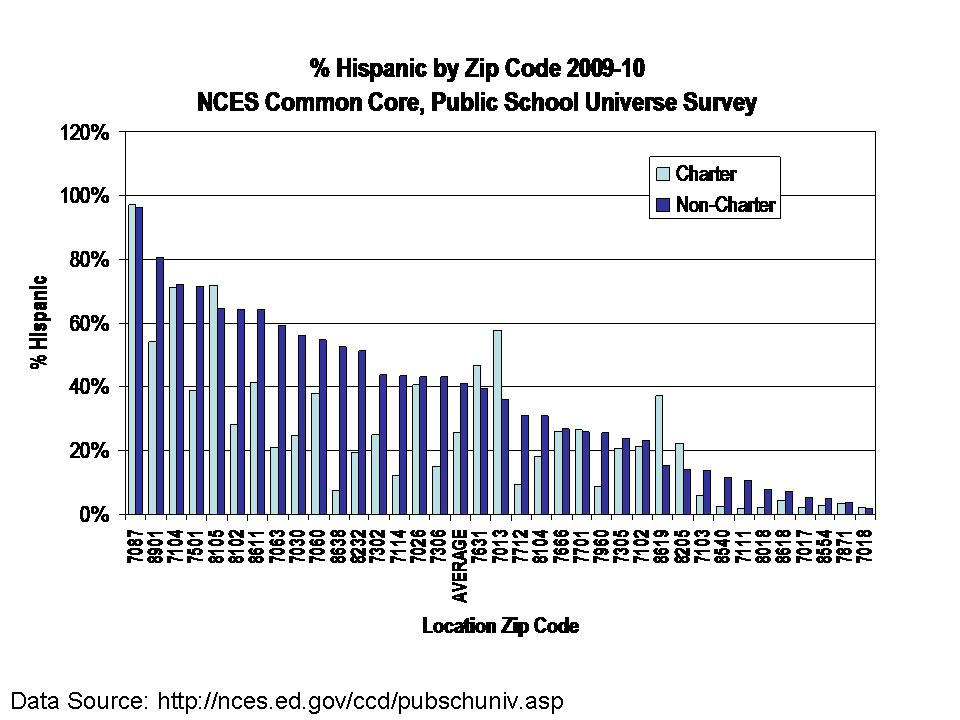

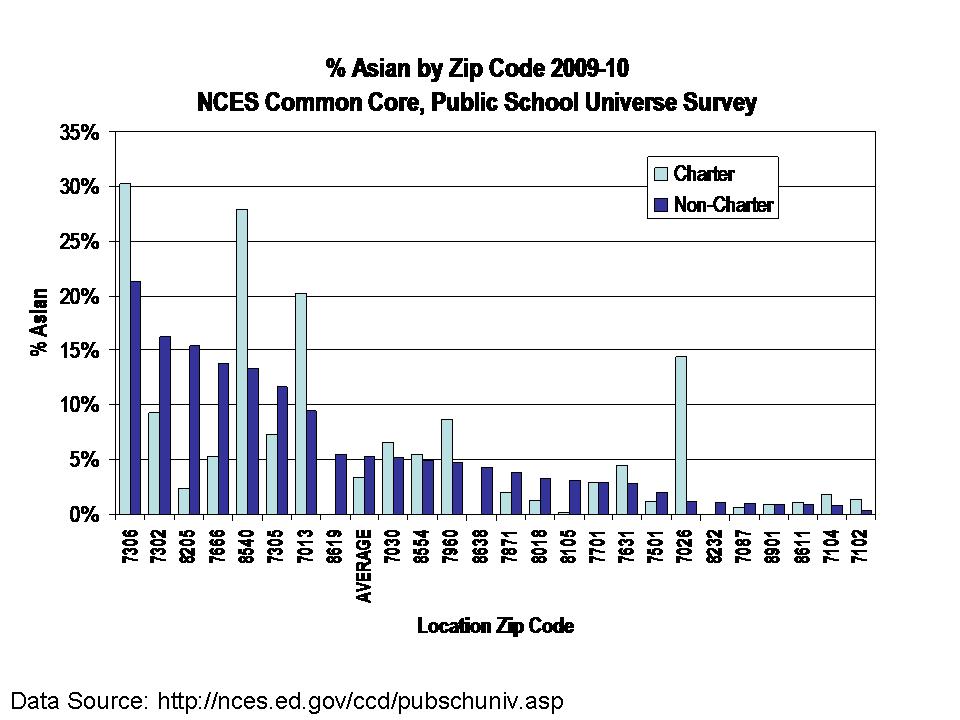

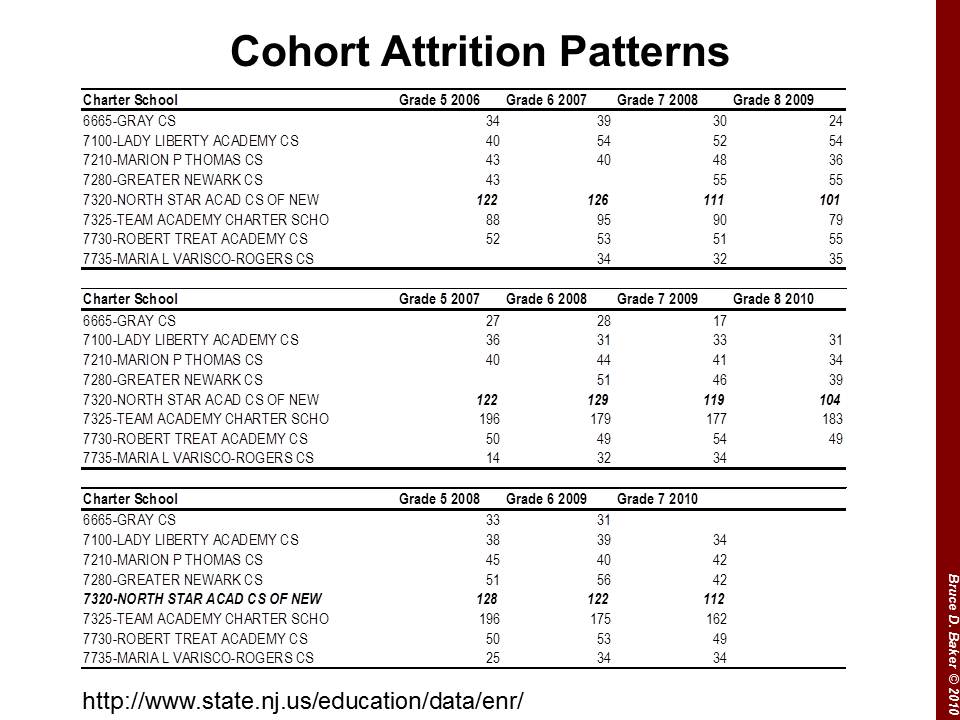

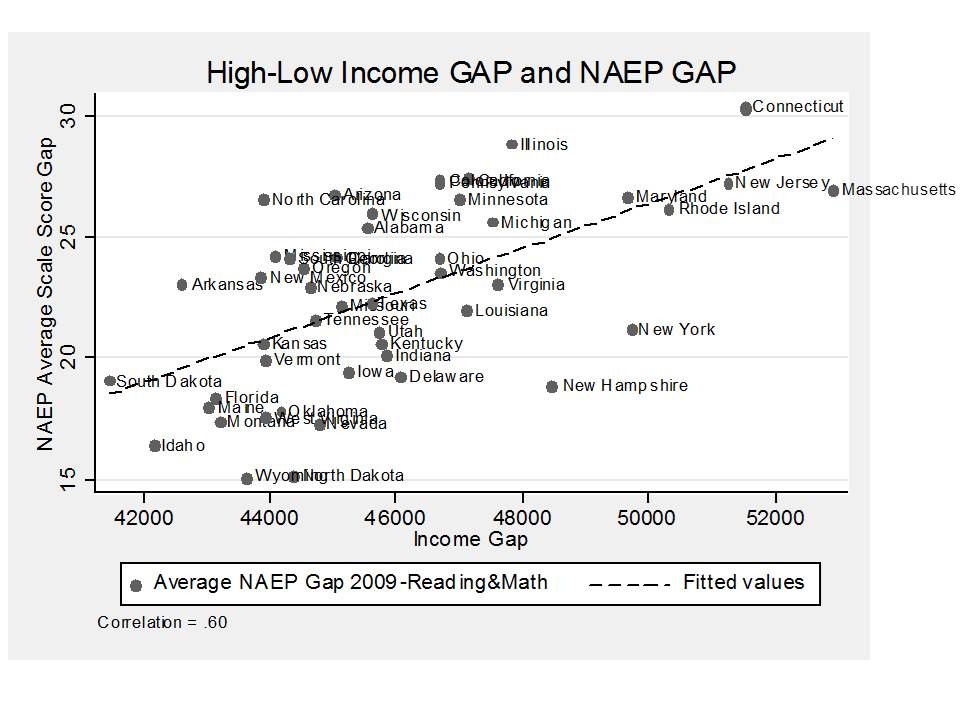

As for highly recognized charter and magnet schools in CT, these schools are actually serving far fewer of the lower income kids within the lower income neighborhoods. So, while they might be doing okay, on average, for the kids they are serving, it is equally likely that they are contributing to the achievement gap as much if not more than helping it. That’s not to say they aren’t helping the students they are serving. But rather that the segregated nature of their services is capitalizing on a peer effect of concentrating more advantaged children. Either way, these schools are unlikely to serve as a broad based solution for CT education quality in general or for resolving achievement gaps.

During this same time period, teachers in NJ and MA also had similar tenure protections and weren’t being tenured or fired based on student test scores. Still somehow, those states had smaller gaps. Further, while both other states do have charter schools, New Jersey which has a much smaller achievement gap than CT has thus far maintained a relatively small charter sector. What Massachusetts and New Jersey have done is to more thoroughly and systematically address school funding disparities.

The Real Disparities:

In a previous series of posts, I discussed what I called Inexcusable Inequalities. I actually used CT as the main example, not because CT is among the worst states on funding inequality, but because I happened to have good data on CT. CT is not among the worst. That special space is reserved for NY, IL, PA and a few others. But CT has its problems. Let’s do a quick walk through. In my previous analysis

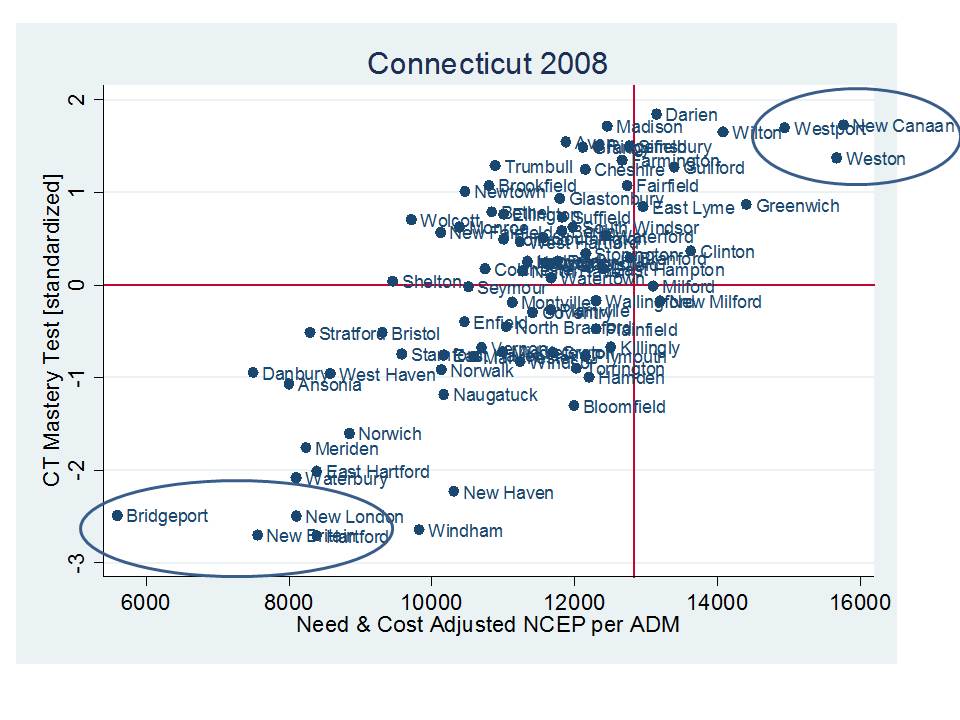

I started my previous post by comparing per pupil spending adjusted for needs and costs across all CT school districts with actual outcomes of those districts in order to categorize CT districts into more and less advantaged groups. The differences, starting with the figure below were pretty darn striking. Districts like New Canaan, Westport and Weston have rather high need and cost adjusted spending, certainly by comparison with Bridgeport, New London or New Britain.

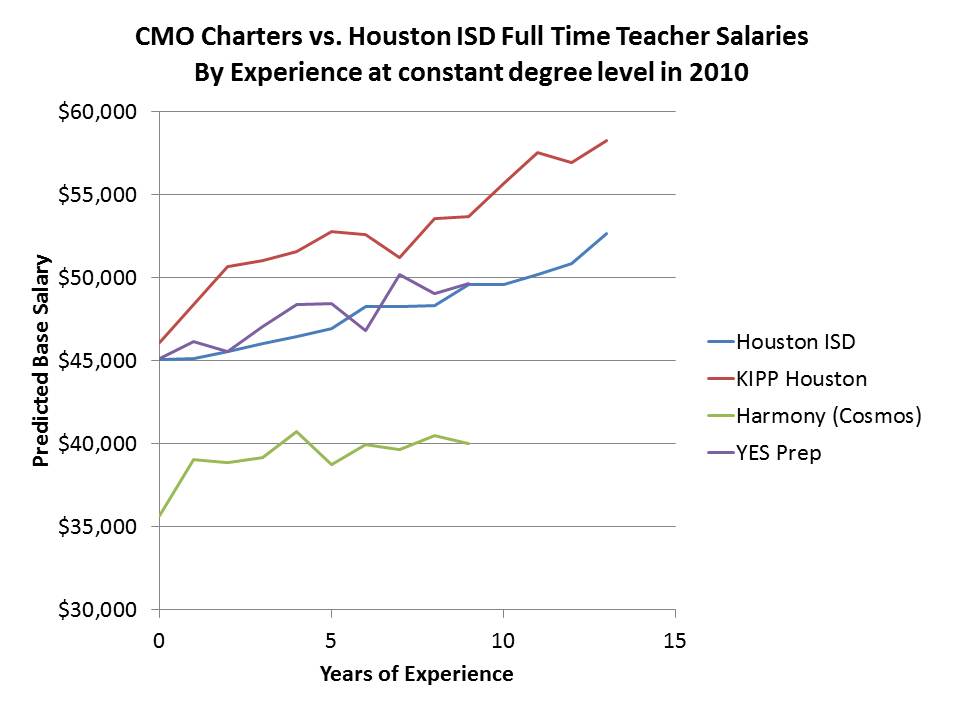

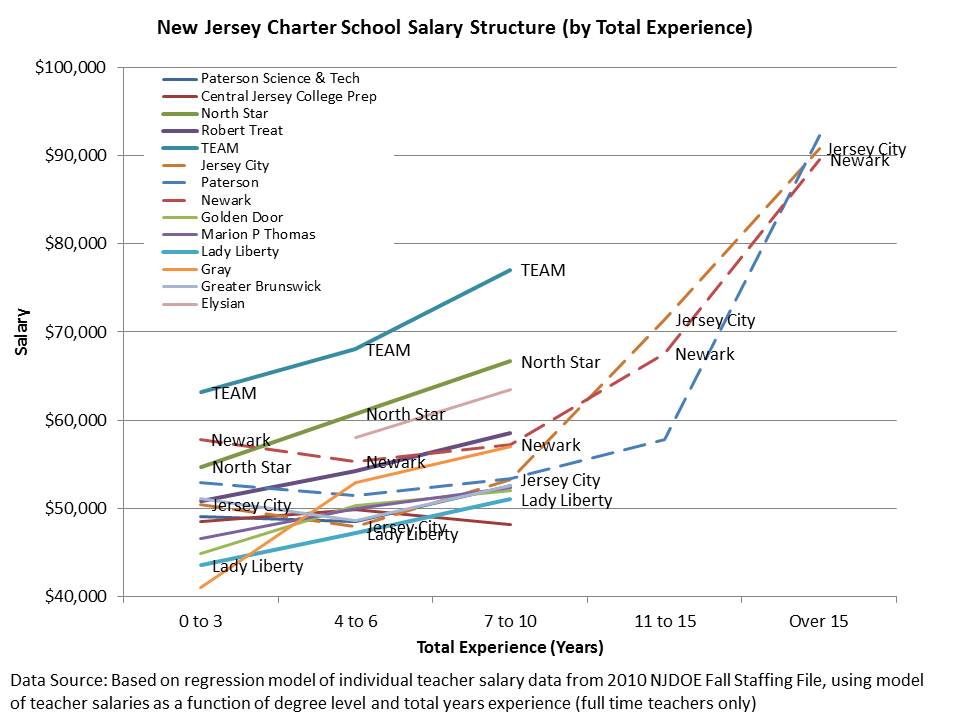

For Illustrative purposes, I then picked a few of the most disadvantaged CT districts and compared them to the most advantaged on a handful of measures – shown below. In this table, I report their nominal spending per pupil – not adjusted for the various needs and additional costs. Even without those adjustments, districts like Bridgeport and New Britain start well behind their more advantaged peers. And among other differences, they pay their teachers less a) on average and b) at any given level of experience or education. Pretty darn hard to recruit and retain quality teachers into these settings given the combination of working conditions and lower pay.

For Illustrative purposes, I then picked a few of the most disadvantaged CT districts and compared them to the most advantaged on a handful of measures – shown below. In this table, I report their nominal spending per pupil – not adjusted for the various needs and additional costs. Even without those adjustments, districts like Bridgeport and New Britain start well behind their more advantaged peers. And among other differences, they pay their teachers less a) on average and b) at any given level of experience or education. Pretty darn hard to recruit and retain quality teachers into these settings given the combination of working conditions and lower pay.

AND MAKING TENURE CONTINGENT ON STUDENT TEST SCORES, OR FIRING TEACHERS BASED ON STUDENT TEST SCORES WON’T FIX THAT! IT WILL FAR MORE LIKELY MAKE IT MUCH, MUCH WORSE!

Salary disparity patterns hold when comparing a) all districts in the upper right of the first figure with b) all districts in the lower left, and c) districts furthers in the lower left (severe disparity):

Salary disparity patterns hold when comparing a) all districts in the upper right of the first figure with b) all districts in the lower left, and c) districts furthers in the lower left (severe disparity):

On top of that, class sizes are also larger in the higher need districts, despite the need for smaller class sizes to aid in closing the achievement gaps for these children (more here).

Further, as I showed in my previous post, the funding disparities have significant consequences for the depth and breadth of curricular offerings available to high students in these districts:

For this analysis, I used individual teacher level data on individual course assignments to determine the distribution of teacher assignments per child, thus characterizing each district’s and group of districts’ offerings (for related research, see: https://schoolfinance101.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/b-baker-mo_il-resourcealloc-aera2011.pdf)

Disadvantaged districts have far fewer total positions per child, and if we click and blow up the graph, we can see some striking discrepancies! Those high need districts have far more special education and bilingual education teachers (squeezing out other options, from their smaller pot!). Those high need districts have only about half the access to teachers in physical education assignments or art, much less access to Band (little or none to Orchestra), and significantly less access to math teachers!

IN REALLY SIMPLE TERMS, UNDER CT POLICIES, HIGH NEED DISTRICTS SUCH AS BRIDGEPORT AND NEW BRITAIN HAVE FAR FEWER RESOURCES AND FAR GREATER NEEDS. THEIR TEACHERS HAVE LOWER SALARIES AND, ON AVERAGE, LARGER CLASSES.

Messing with teacher evaluation, especially in ways as likely to do harm as to do good, is an unfortunate distraction at best. Doing so on the basis that those are the policy changes needed to close Connecticut’s achievement gap reflects an astounding degree of utter obliviousness!

What about those amazing CT charter and magnet schools? Aren’t they the ultimate scalable solution?

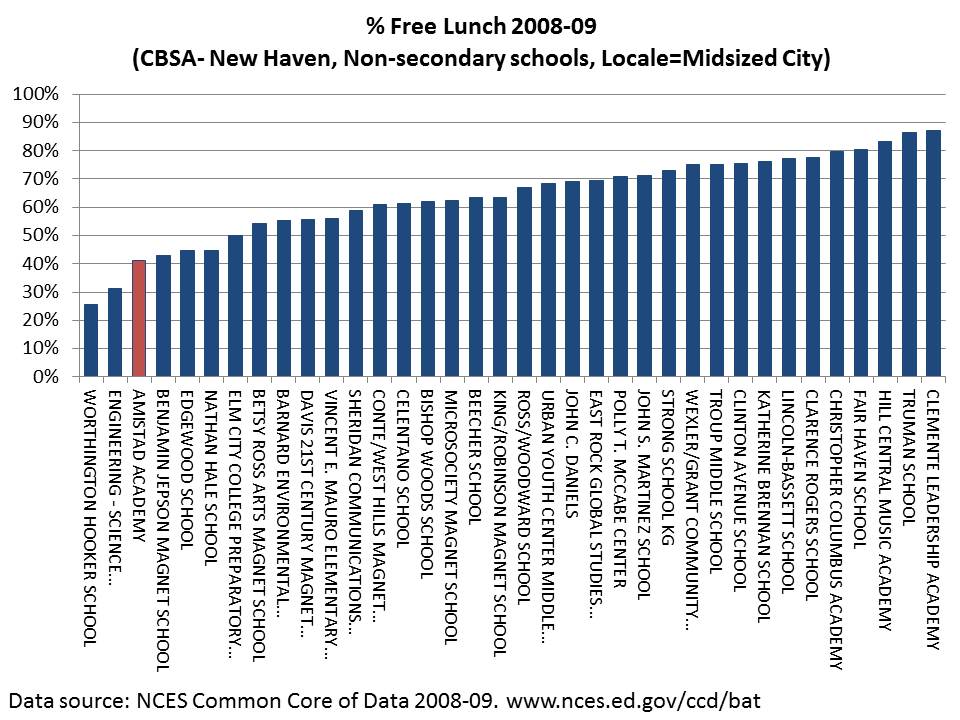

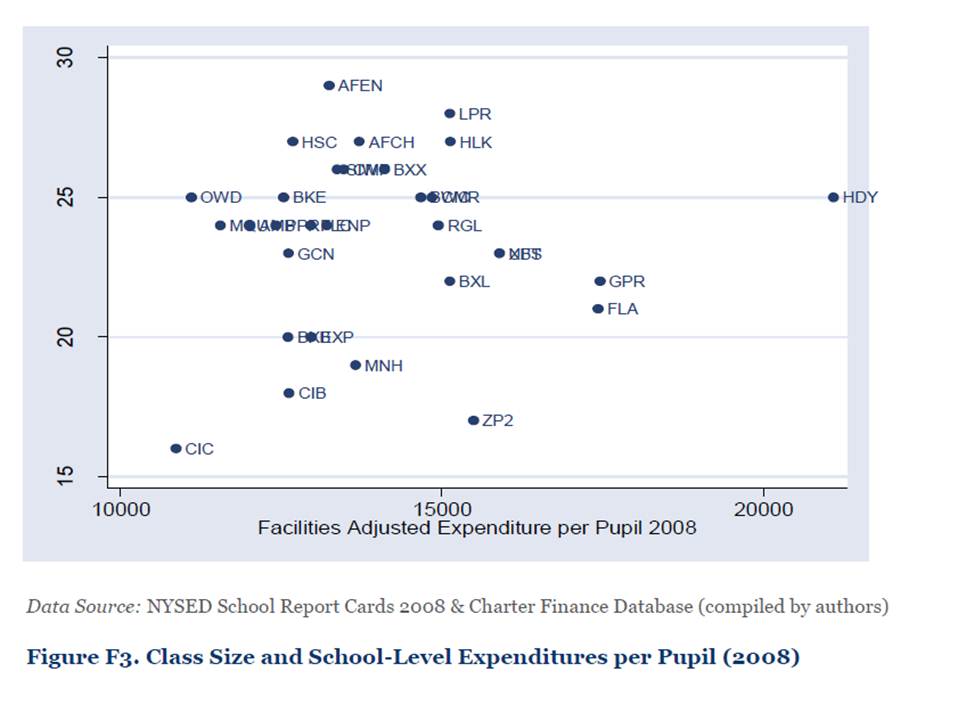

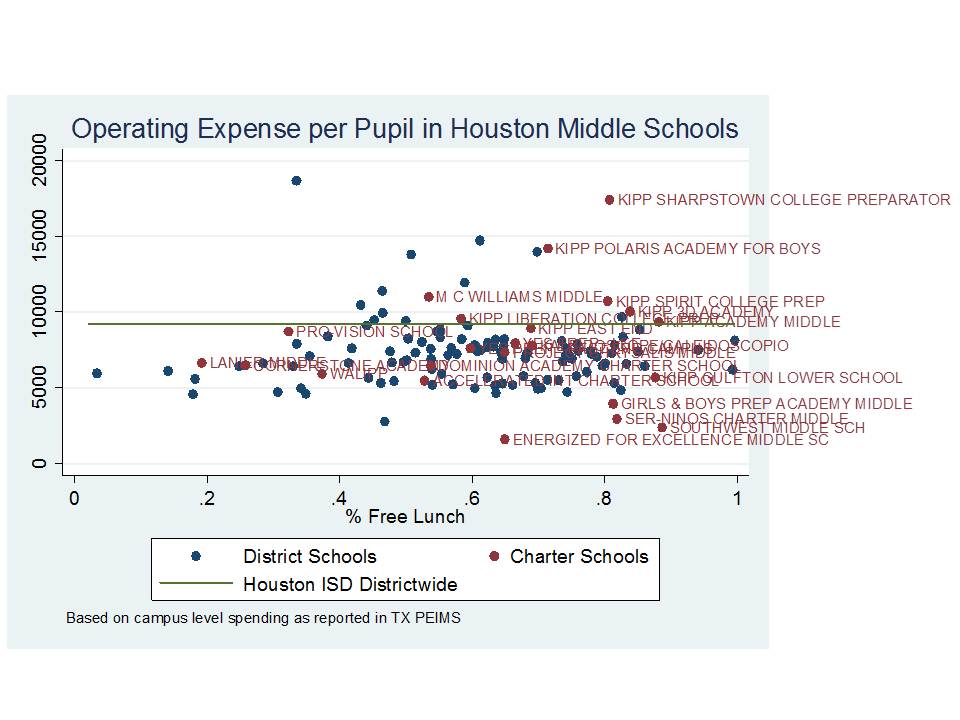

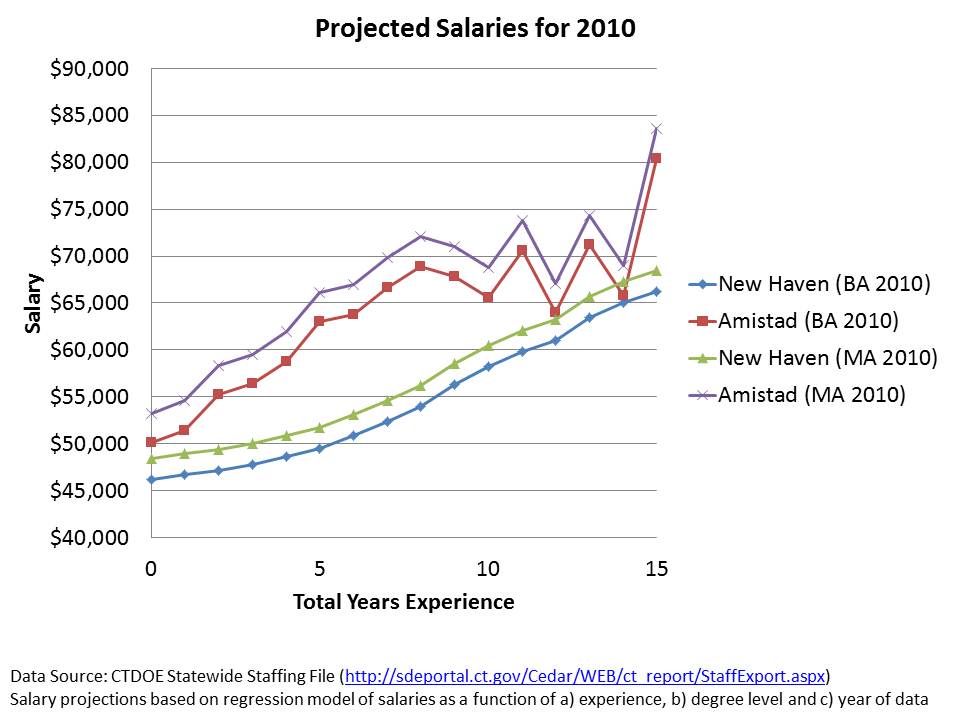

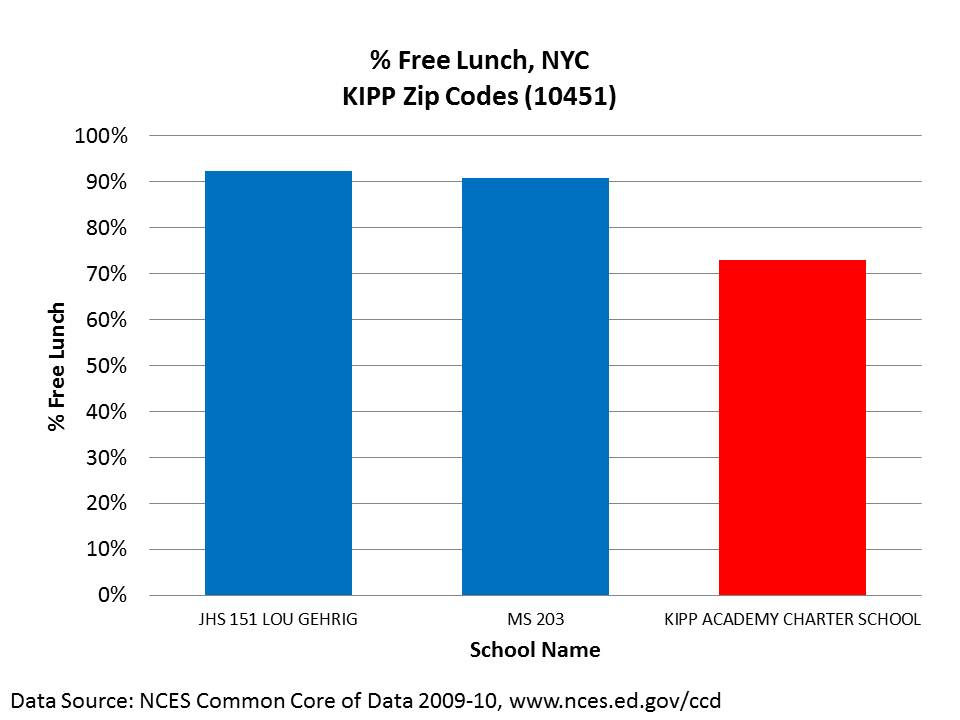

I’ve written much more detail here, about the issue of whether renowned CT charter schools actually “do more, with less while serving the same students.” Here are a few quick graphs. First, Amistad Academy of New Haven in context, by % free lunch:

Next, Capital Prep in Hartford in context. Now, I typically wouldn’t (shouldn’t) have to point out that a small selective magnet program drawing students across district lines is simply NOT REPRESENTATIVE and not likely a scalable solution for all kids. It’s a potentially good option for those with access, and much of the benefit of the option likely rests in selective peer group effect (as noted above). I feel compelled, however, to point out how Capital Prep is (obviously) not a typical school only because the head of the school seems to be trying to argue that it is a model scalable reform Really? Really? I mean…. REALLY?):

But what about Governor Malloy’s funding plan? That’ll fix it! Won’t it?

Amidst all of the reformy platitudes, misguided and fact-challenged placards and the like, there were occasional references to Governor Malloy’s changes to the state school finance formula – seemingly implying that the Governor has taken major steps toward making the (supposedly already overfunded) system fairer. There was certainly no outrage expressed at the types of disparities I note above, and all the warm fuzzy feeling anyone could possibly conjure that any finance package tied to the vast batch of reformyness on steriods would be sufficient to get the job done.

After all, new aid would be progressively distributed. Those poor districts would get, on average, about… oh… a whopping new $250 per pupil while richer districts would get only about $50 per pupil. And with this astounding outlay of fiscal effort, the most important thing is to make sure it doesn’t just go straight into the pockets of those union-lacky-lazy-self-interested-teachers, of course – or at least certainly not the “ineffective” ones.

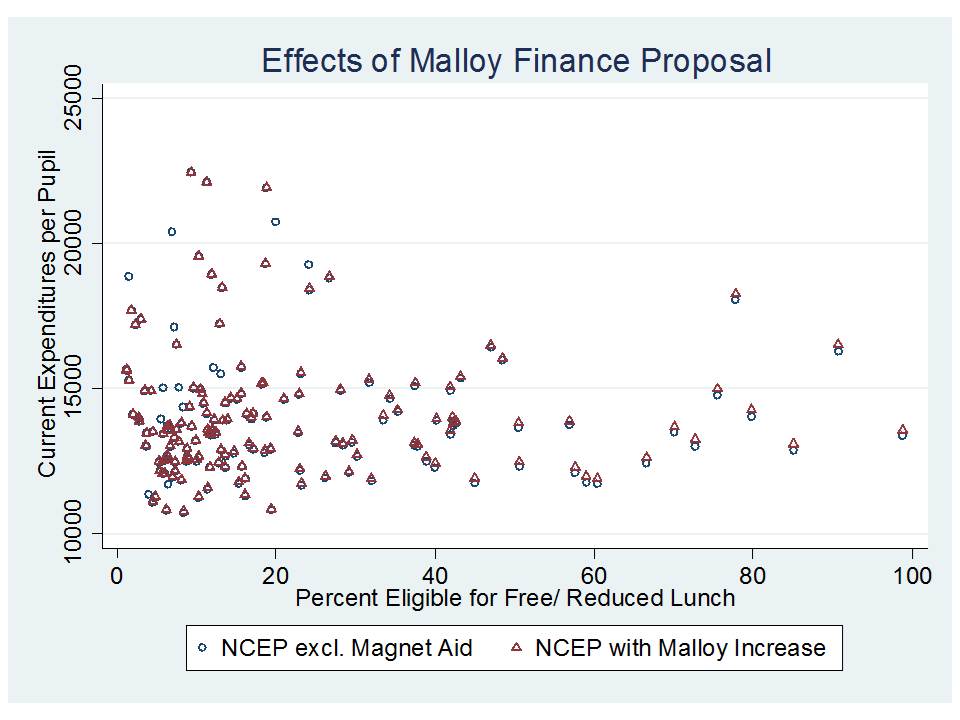

Here are the effects of the Malloy funding increases, on a per pupil basis, if added on to Net Current Expenditures per Pupil (pulling out magnet school aid which creates a distorted representation for New Haven and Hartford):

What we have in this picture is each district as a dot (circle or triangle). Districts are sorted from low to high percent free/reduced lunch along the horizontal axis. Net Current Expenditures are on the vertical axis. Blue Circles represent current (okay, last year) levels of current expenditures per pupil. RED TRIANGLES REPRESENT THE ADDITION OF MALLOY AID. Wow… that’s one heck of a difference. That should certainly fix the disparities I laid out above! NOT!

What we have in this picture is each district as a dot (circle or triangle). Districts are sorted from low to high percent free/reduced lunch along the horizontal axis. Net Current Expenditures are on the vertical axis. Blue Circles represent current (okay, last year) levels of current expenditures per pupil. RED TRIANGLES REPRESENT THE ADDITION OF MALLOY AID. Wow… that’s one heck of a difference. That should certainly fix the disparities I laid out above! NOT!

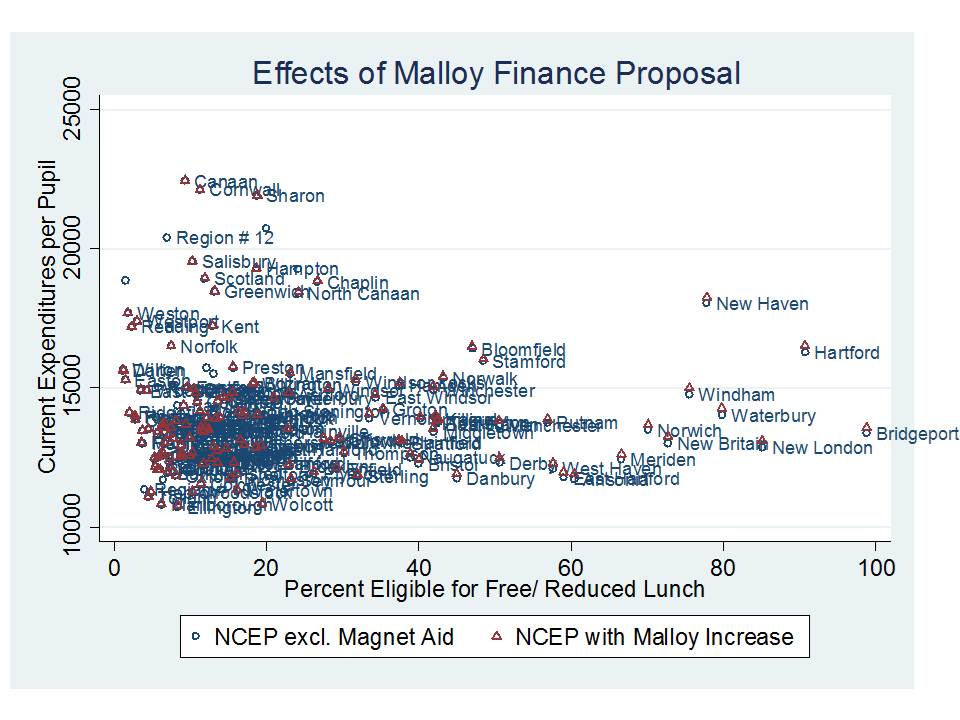

Here it is with district names added, so you can see where some of our more disadvantaged districts start and end up:

Not that helpful for Bridgeport or New Britain, is it?

Not that helpful for Bridgeport or New Britain, is it?

To summarize:

The fact is that EQUITABLE AND ADEQUATE FUNDING IS THE NECESSARY UNDERLYING CONDITION FOR IMPROVING EDUCATION QUALITY IN CONNECTICUT AND REDUCING ACHIEVEMENT GAPS!!!!!! (related research: http://www.tcrecord.org/library/content.asp?contentid=16106)

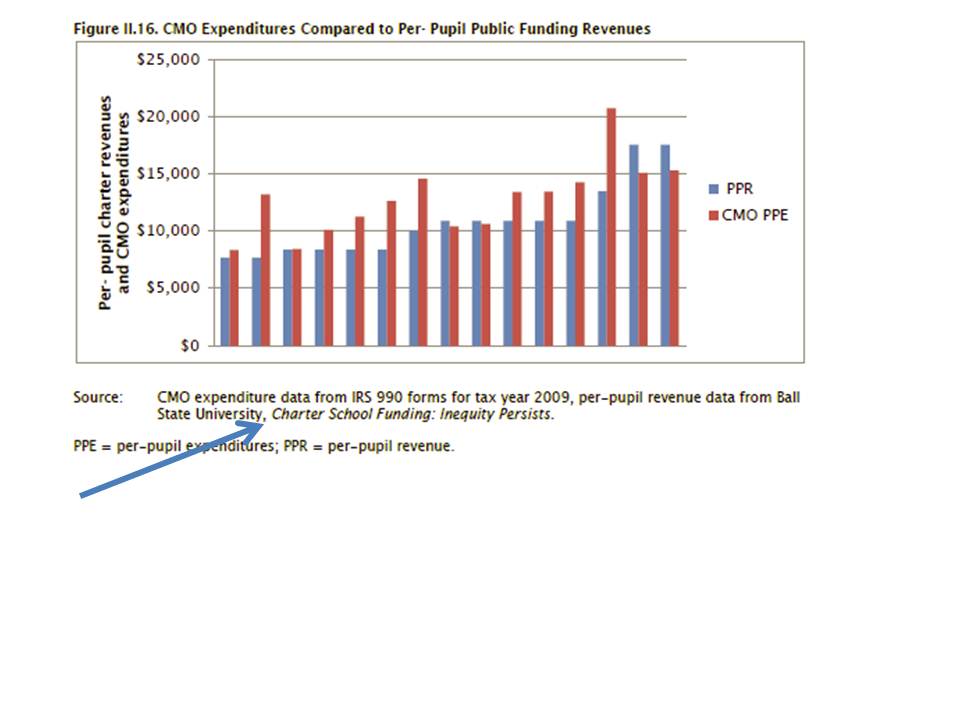

Equitable and adequate funding is a necessary underlying condition for running any quality school, be it a traditional public school, charter school or private school. Money matters and it matters regardless of the type of school we’re talking about.

Equitable and adequate funding is required for recruiting and retaining teachers in Connecticut’s high need, currently under-resourced schools (something charter operators realize). Recruiting and retaining teachers to work in these communities will take more, not less money.

Reformy platitudes (and fact-challenged placards) about tenure reform won’t change that. And altering the job security landscape to move toward ill-conceived evaluation frameworks and flawed metrics will likely hurt far more than it will help.

It’s time to pack up the reformy circus, load up the buses and shred the placards and have some real, substantive conversations about improving the quality and equality of public schooling in Connecticut.