My doctoral student Mark Weber and I have just completed our second report evaluating the impact of the proposed One Newark plan on Newark schools, teachers and the students they serve. In this post, I will try to provide a condensed summary of our findings and the connections between the two reports.

In our first report, we evaluated the statistical bases for the placement of Newark district schools into various categories of consequences. Those categories are as follows:

- No Major Change: Neither the staff nor students will experience a major restructuring. While some schools may be resited, there will otherwise be little impact on the school. We have classified many of the schools slated for redesign in this category, as there appears to be no substantial change in the student body, the staff, or the mission of the school in NPS documents; however, we recognize that this may change as One Newark is implemented, and that some of these schools may eventually belong in different categories.

- Renew: As staff will have to reapply for their positions, students may see a large change in personnel. The governance of the school may change in other ways.

- Charter Takeover: While students are given “priority” if they choose to apply to the charter, there appears to be no guarantee they will be accepted.

- Close: We consider a school “closed” when it ceases to function in its current form, its building is being divested or repurposed, and it is not being taken over by a charter operator.

- Unknown: The “One Newark” documents published by NPS are ambiguous about the fate of the school.

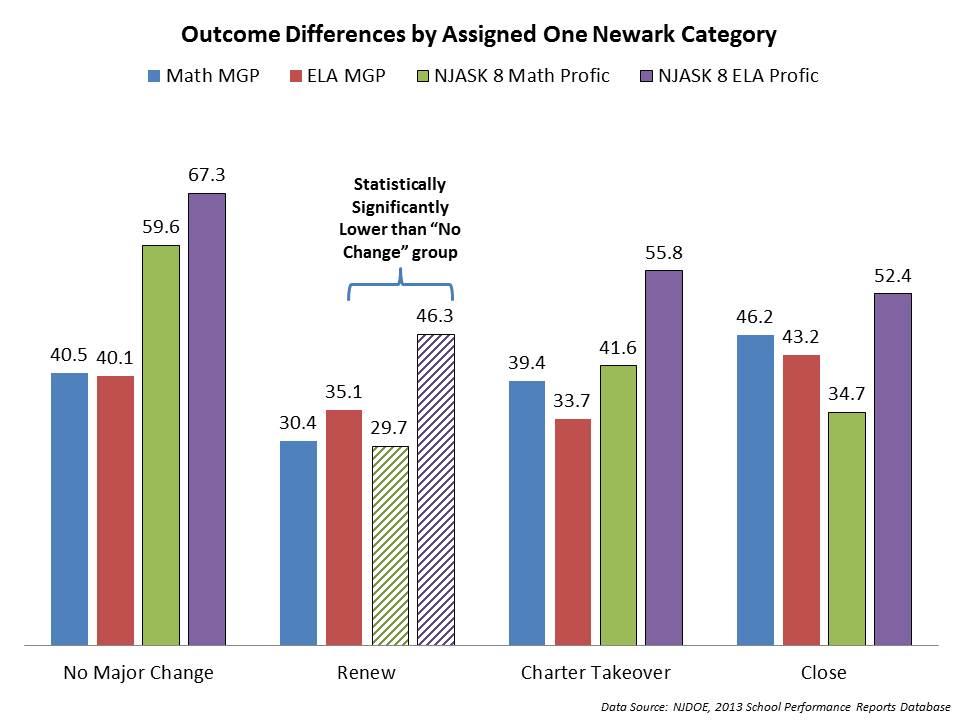

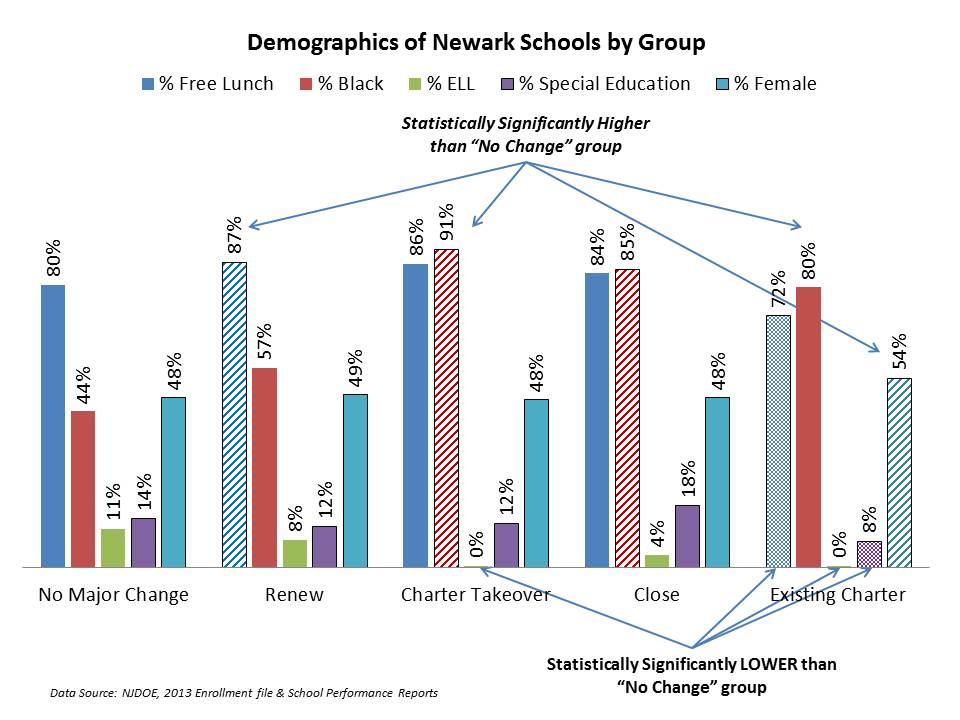

We evaluated the extent to which schools, by these classifications differed in terms of a) performance measures, b) student population characteristics and c) facilities indicators. We also tested whether these factors might be used to predict to which group schools were assigned. What we found was:

- Measures of academic performance are not significant predictors of the classifications assigned to NPS schools by the district, when controlling for student population characteristics.

- Schools assigned the consequential classifications have substantively and statistically significantly greater shares of low income and black students.

- Further, facilities utilization is also not a predictor of assigned classifications, though utilization rates are somewhat lower for those schools slated for charter takeover.

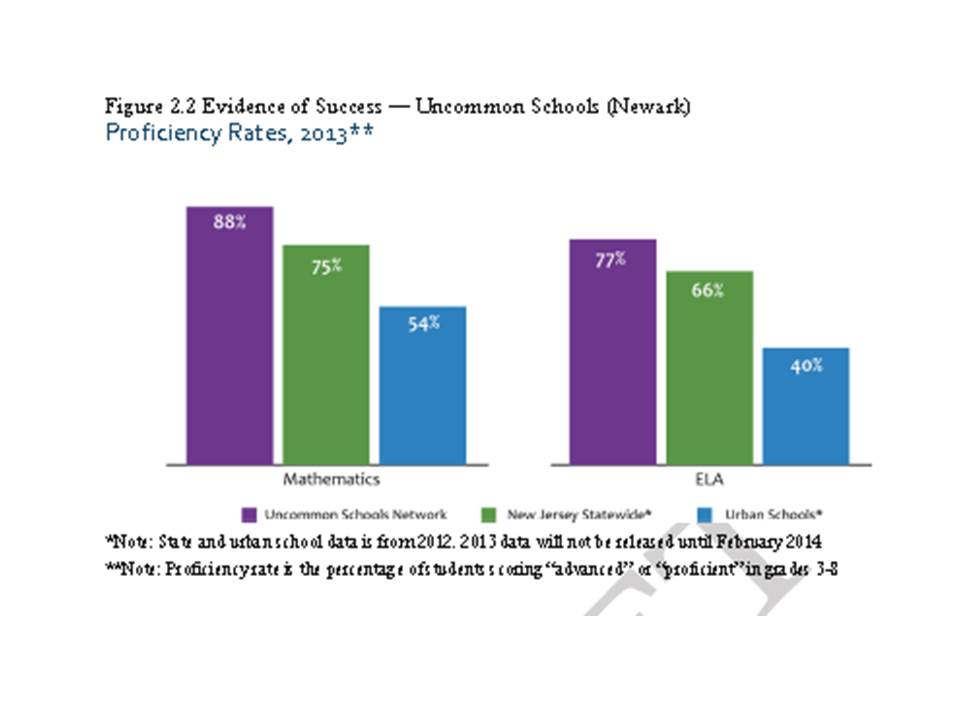

- Proposed charter takeovers cannot be justified on the assumption that charters will yield better outcomes with those same children. This is because the charters in question do not currently serve similar children. Rather they serve less needy children and when adjusting school aggregate performance measures for the children they serve, they achieve no better current outcomes on average than the schools they are slated to take over.

- Schools slated for charter takeover or closure specifically serve higher shares of black children than do schools facing no consequential classification. Schools classified under “renew” status serve higher shares of low-income children.

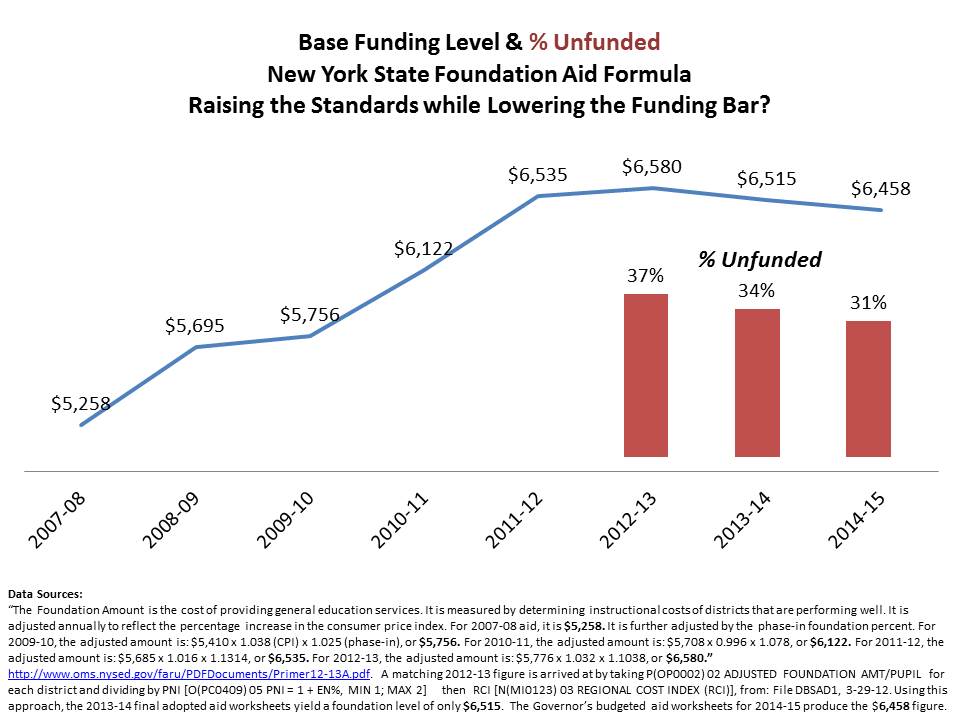

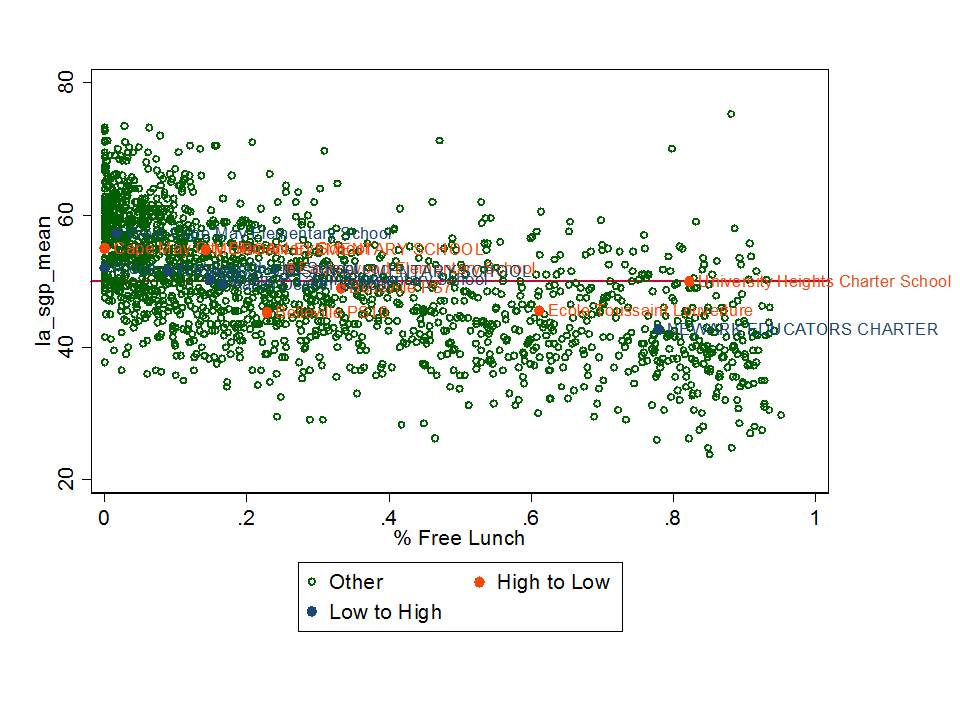

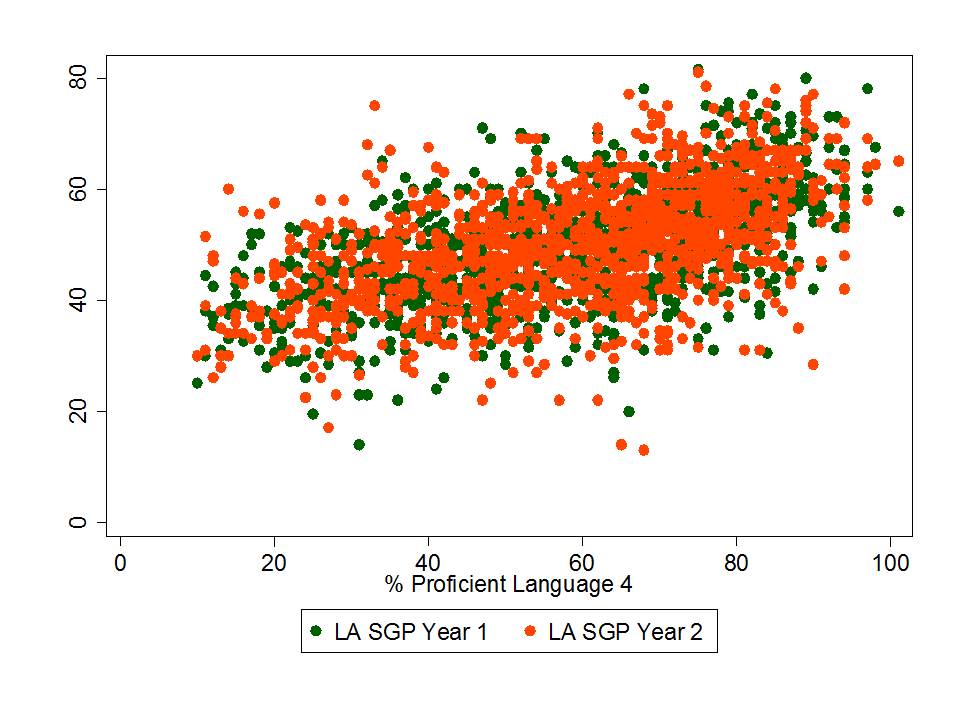

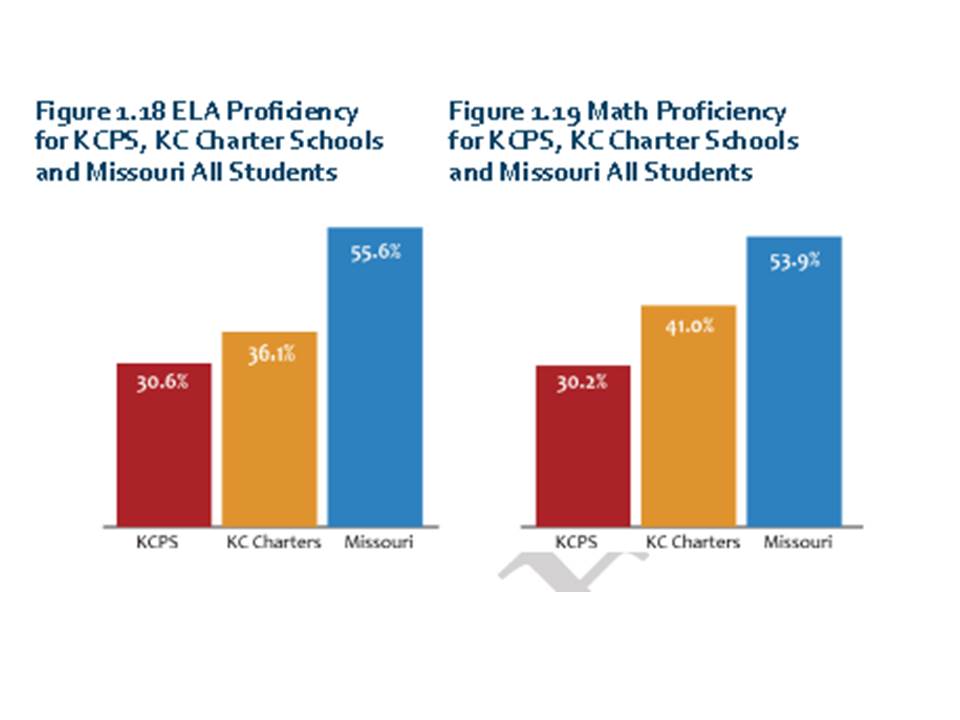

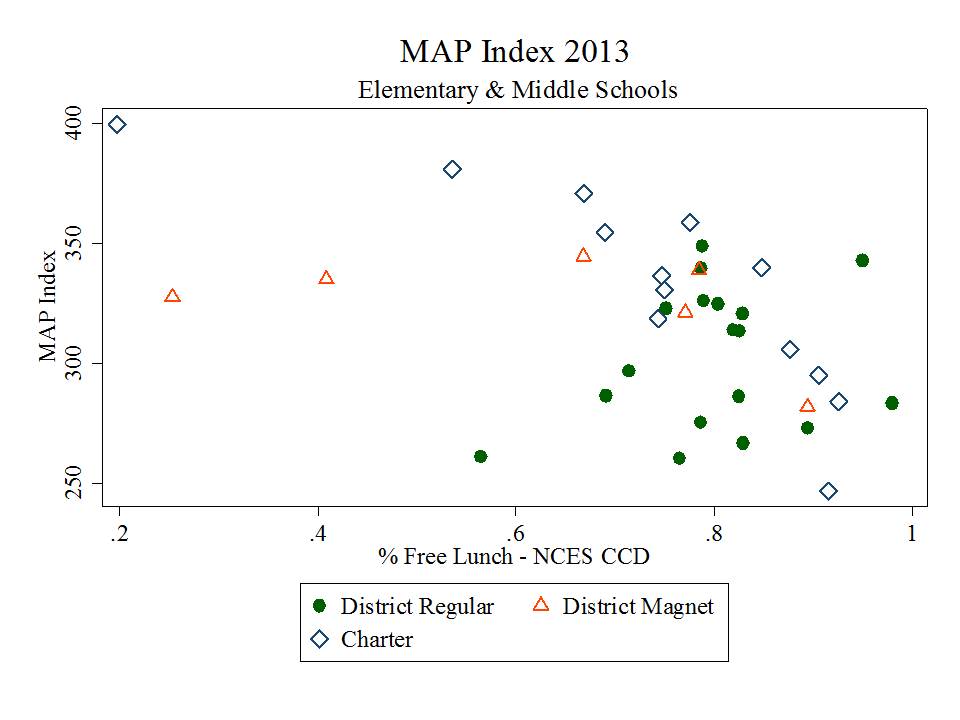

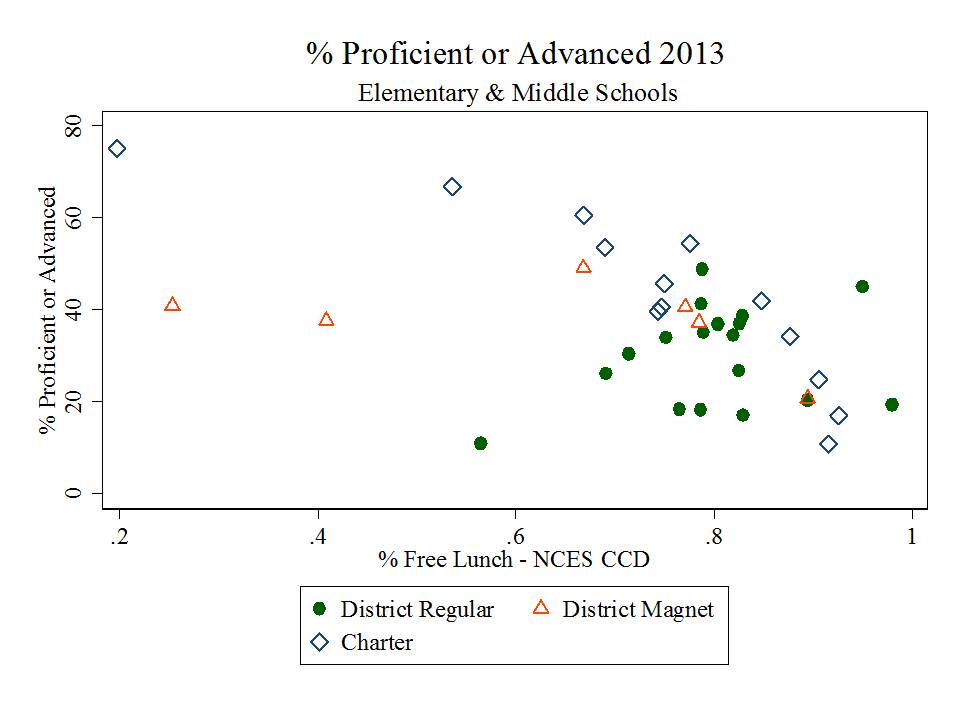

Figure 1

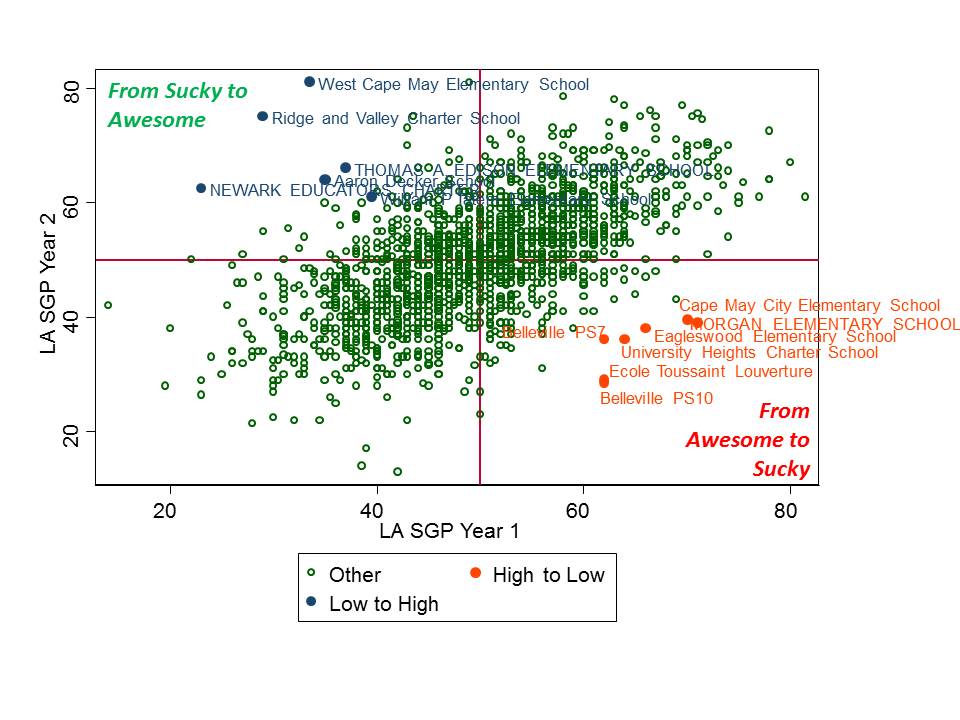

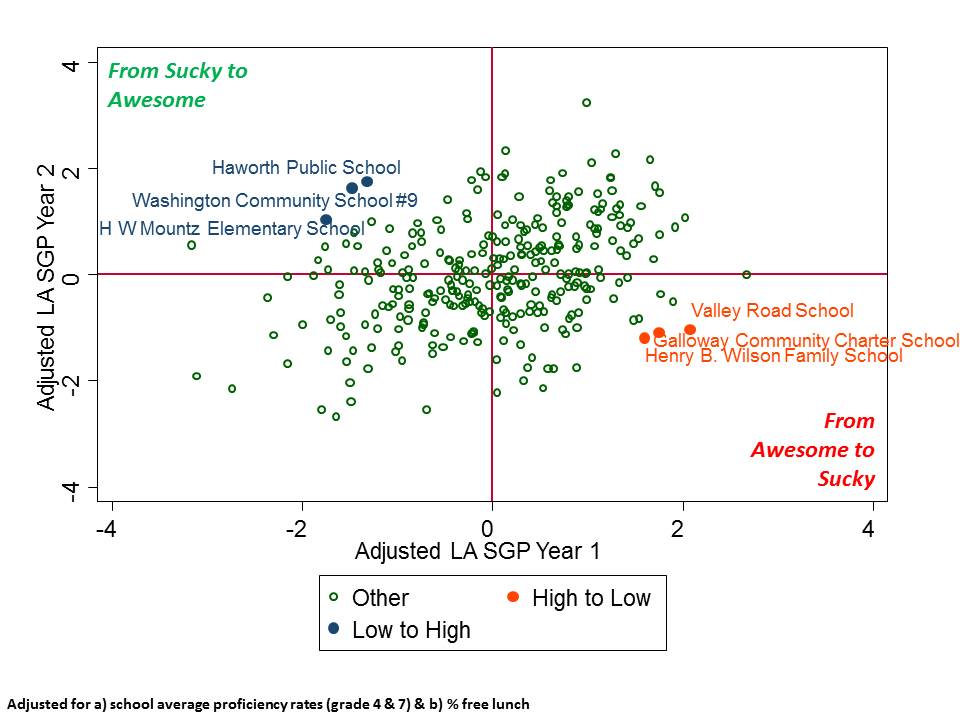

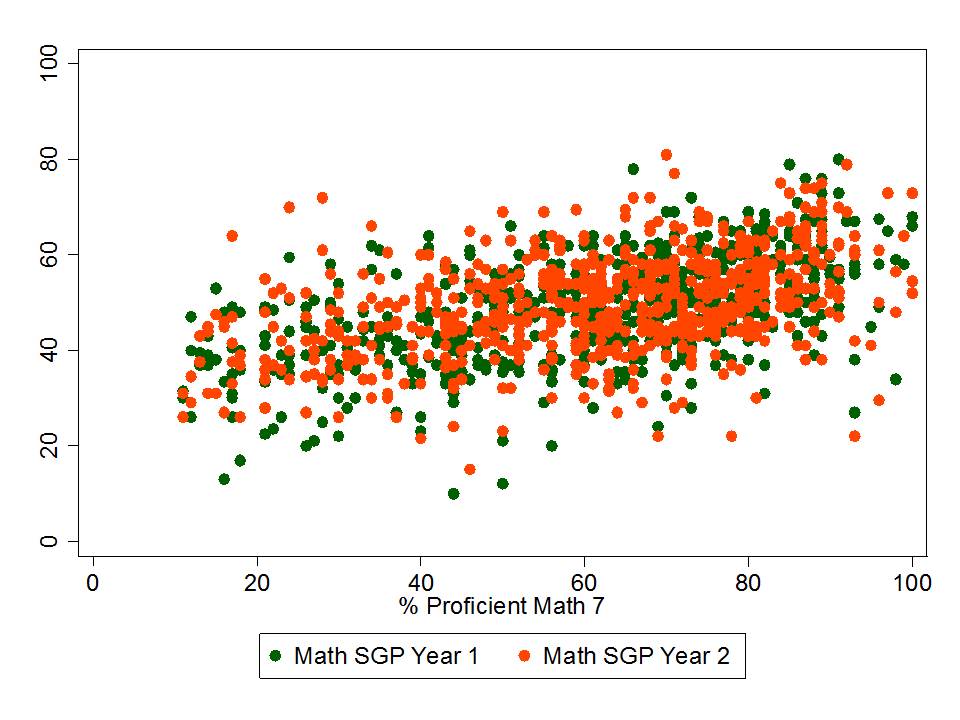

Figure 2

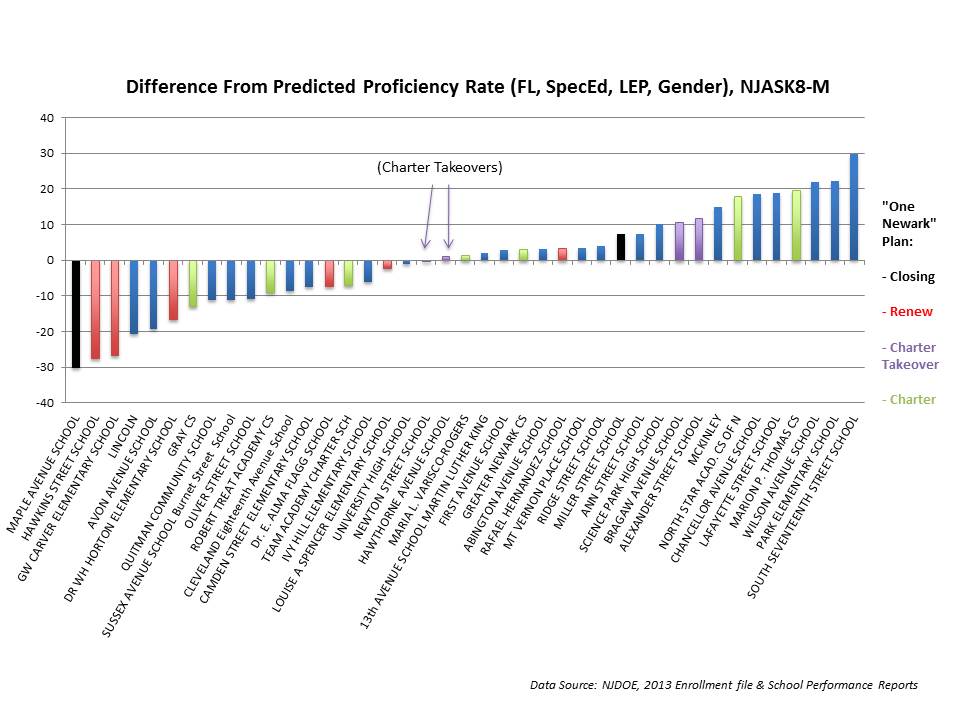

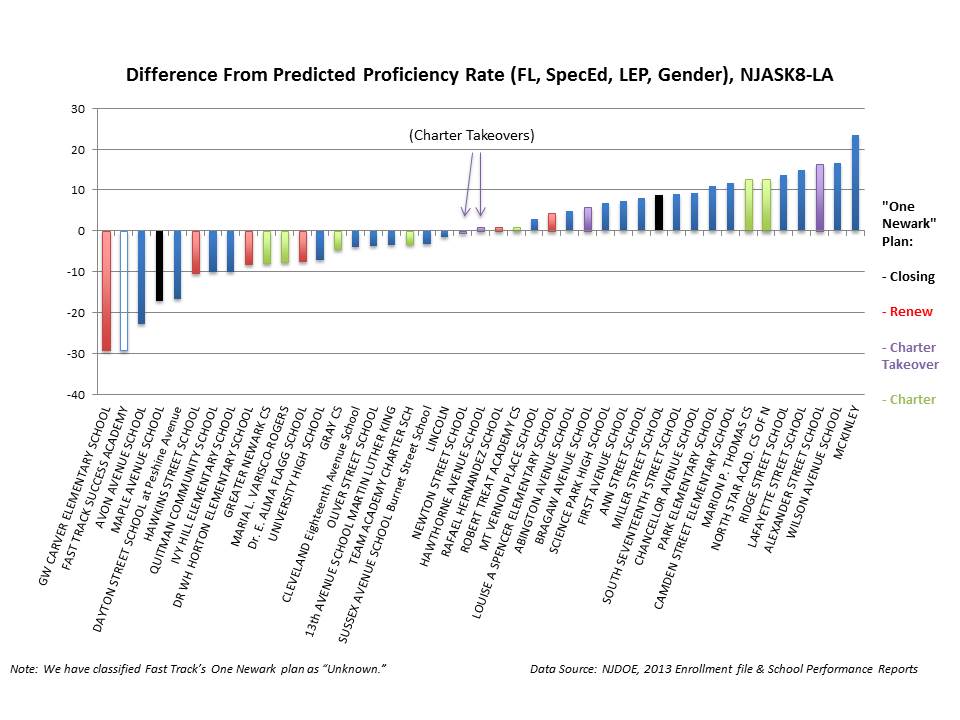

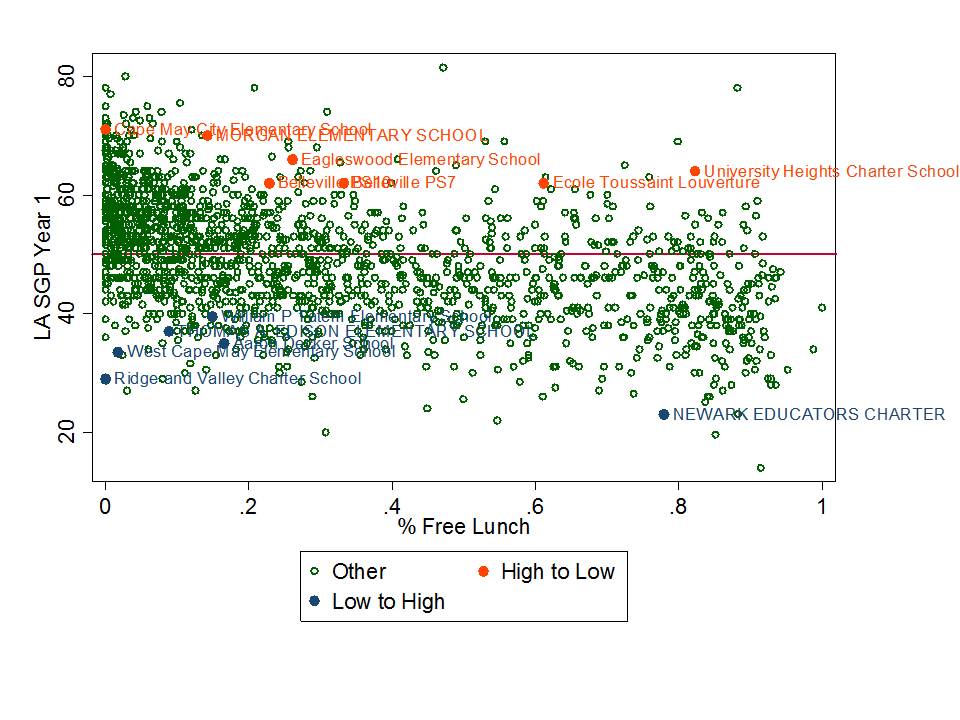

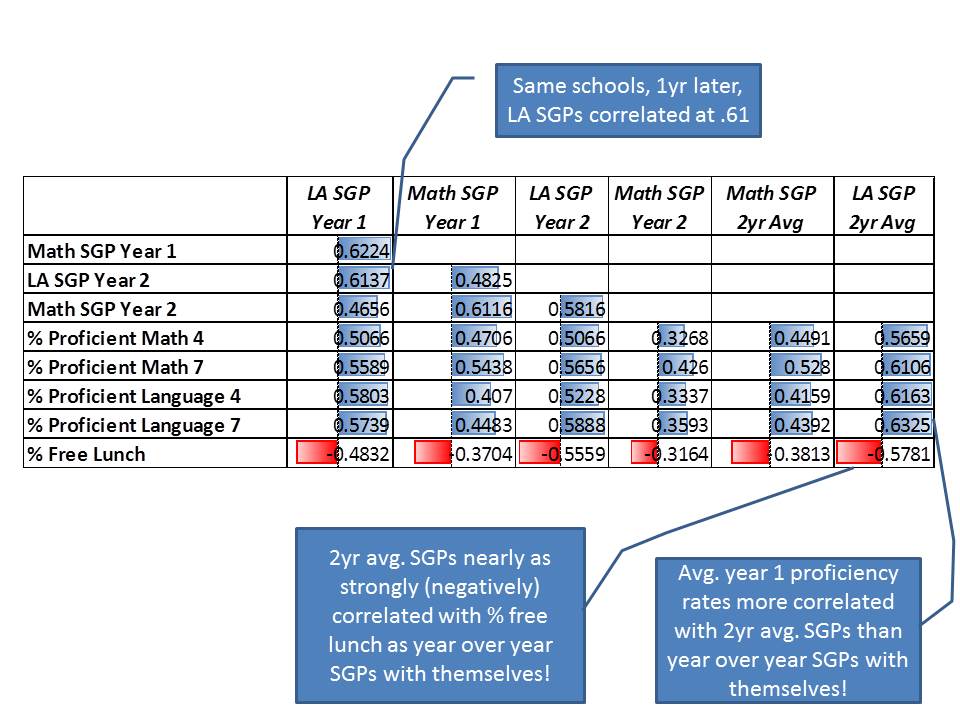

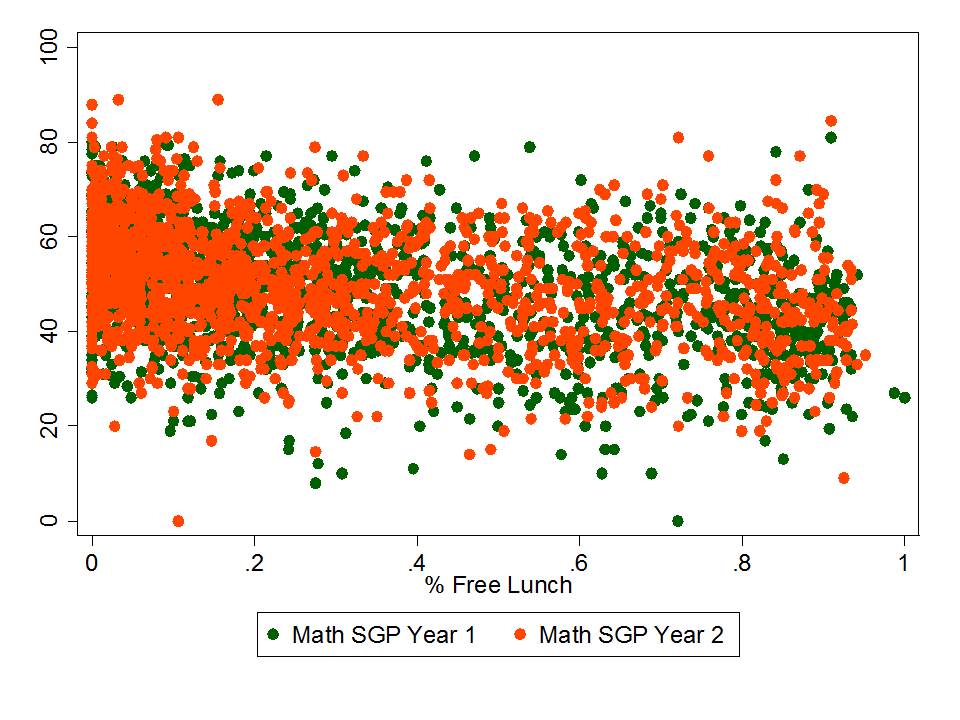

Figure 3

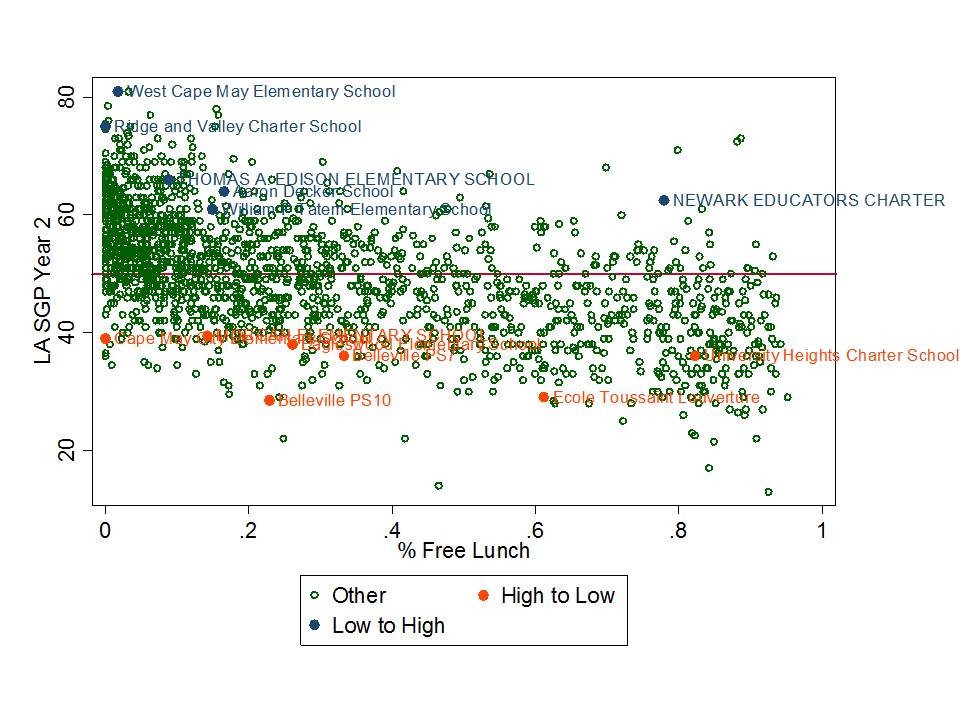

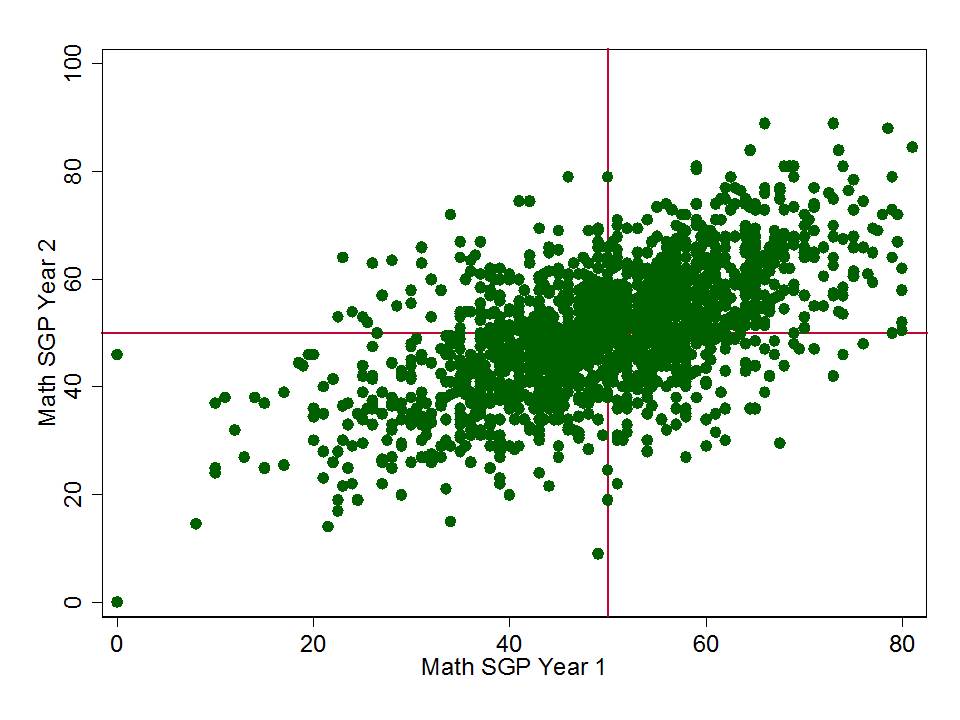

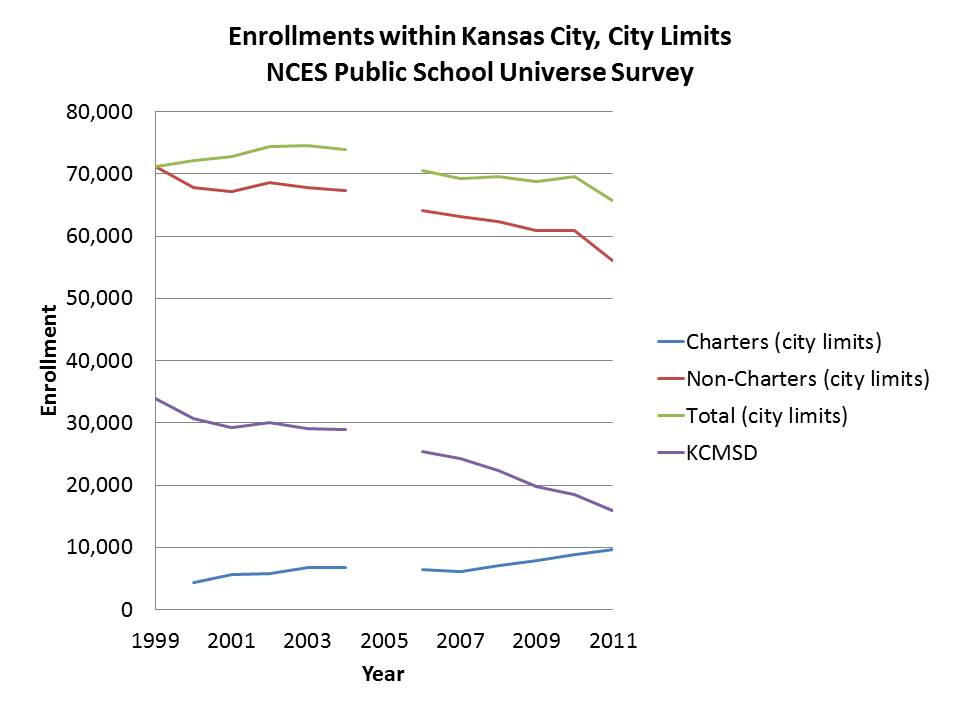

Figure 4

These last two figures are particularly important because what they show is that after we adjust for student population characteristics, schools slated for takeover by charters in some cases actually outperform the charters assigned to take them over. While North Star Academy is a relative high performer, we are unable here to account for the fact that North Star loses about half of their students between grades 5 and 12.

These findings raise serious concerns at two levels. First, these findings raise serious questions about the districts own purported methodology for classifying schools. Our analyses suggest the district’s own classifications are arbitrary and capricious, yielding racially and economically disparate effects. Second, the choice, based on arbitrary and capricious classification, to subject disproportionate shares of low income and minority children to substantial disruption to their schooling, shifting many to schools under private governance, may substantially alter the rights of these children, their parents and local taxpayers.

One Newark is a program that appears to place sanctions on schools – including closure, charter takeover, and “renewal” – on the basis of student test outcomes, without regard for student background. The schools under sanction may have lower proficiency rates, but they also serve more challenging student populations: students in economic disadvantage, students with special educational needs, and students who are Limited English Proficient.

There is a statistically significant difference in the student populations of schools that face One Newark sanctions and those that do not. “Renew” schools serve more free lunch-eligible students, which undoubtedly affects their proficiency rates. Schools slated for charter takeover and closure serve larger proportions of students who are black; those students and their families may have their rights abrogated if they choose to stay at a school that will now be run by a private entity.

There is a clear correlation between student characteristics and proficiency rates on state tests. When we control for student characteristics, we find that many of the schools slated for sanction under One Newark actually have higher proficiency rates than we would predict. Further, the Newark charter schools that may take over those NPS schools perform worse than prediction.

There is, therefore, no empirical justification for assuming that charter takeovers will work, when after adjusting for student populations, schools to be taken over actually outperform the charters assigned to take them over. Further, these charters have no track record actually serving populations like those attending the schools identified for takeover.

Our analysis calls into question NPS’s methodology for classifying schools under One Newark. Without statistical justification that takes into account student characteristics, the school classifications appear to be arbitrary and capricious.

Further, our analyses herein find that the assumption that charter takeover can solve the ills of certain district schools is specious at best. The charters in question, including TEAM academy, have never served populations like those in schools slated for takeover and have produced only comparable current outcome levels relative to the populations they actually serve.

Finally, as with other similar proposals sweeping the nation arguing to shift larger and larger shares of low income and minority children into schools under private and quasi-private governance, we have significant concerns regarding the protections of the rights of these children and taxpayers in these communities.

In our second report, we evaluated the distribution of staffing consequences from the One Newark proposal. For us, the One Newark plan raised immediate concerns of possible racial disparity both for students and their teachers. As such, we decided to evaluate the racially disparate impact of the plan on teachers, in relation to the students they serve and also to explore the parallels between the One Newark proposal and past practices which disadvantaged minority teachers. In our second report, we found:

- There is a historical context of racial discrimination against black teachers in the United States, and “choice” systems of education have previously been found to disproportionately affect the employment of these teachers. One Newark appears to continue this tradition.

- There are significant differences in race, gender, and experience in the characteristics of NPS staff and the staff of Newark’s charter schools.

- NPS’s black teachers are far more likely to teach black students; consequently, these black teachers are more likely to face an employment consequence as black students are more likely to attend schools sanctioned under One Newark.

- Black and Hispanic teachers are more likely to teach at schools targeted by NJDOE for interventions – the “tougher” school assignments.

- The schools NPS’s black and Hispanic teachers are assigned to lag behind white teachers’ schools in proficiency measures on average; however, these schools show more comparable results in “growth,” the state’s preferred measure for school and teacher accountability.

- Because the demographics of teachers in Newark’s charter sector differ from NPS teacher demographics, turning over schools to charter management operators may result in an overall Newark teacher corps that is more white and less experienced.

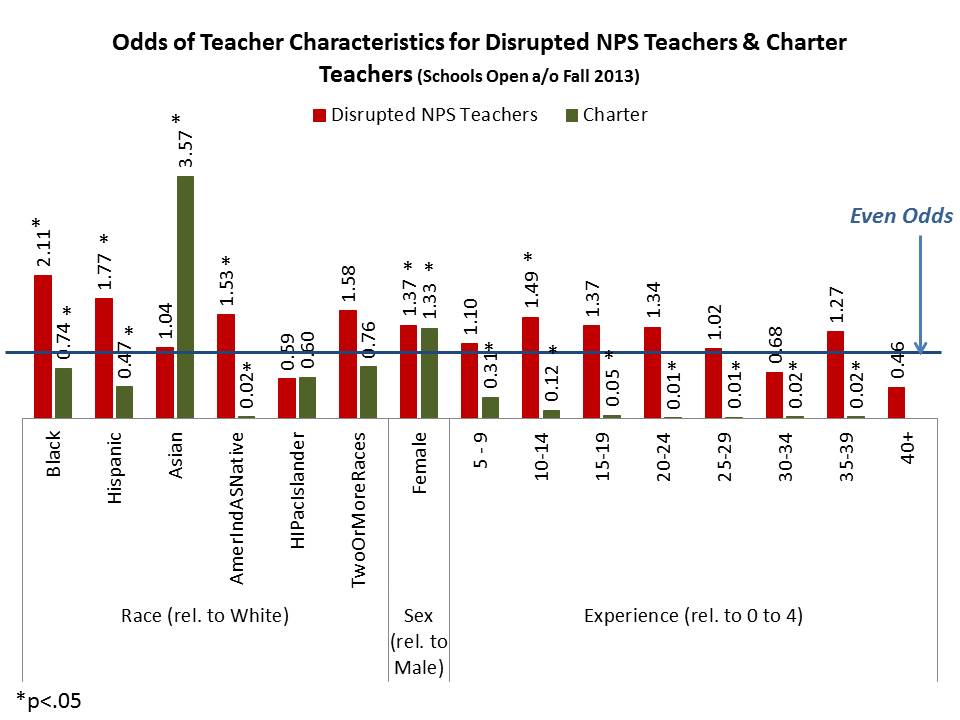

Figure 5

This figure is the real kicker here. This figure, based on two separate logistic regression models characterizes a) the likelihood that an NPS teacher is in a school which faces consequences and b) the likelihood that a teacher is a charter school teacher. That is, we estimate the odds, by race, experience and other factors that a teacher is in a school where they are likely to face job consequences and the odds that a teacher works in the favored subset of charter schools. We find that:

- NPS teachers who face employment consequences as a function of One Newark are 2.11 times as likely to be black as to be white, and 1.766 times as likely to be Hispanic as white.

- By contrast, charter school teachers in Newark who are not only protected by the plan, but given the opportunity in some cases to take over the schools and thus the jobs of those NPS teachers, are only 74% as likely to be black as to be white, 47% as likely to be Hispanic as white, and 3.6 times more likely to be Asian than white.

- Both charter teachers and NPS teachers facing employment consequences tend to be female.

- NPS teachers who face employment consequences as a function of One Newark are about 50% more likely to have 10 to 14 years of experience compared to their peers with 0 to 4 years, and 37% more likely to have 15 to 19 years of experience compared to their peers with 0 to 4 years.

- Charter teachers, who again may be given the opportunity to take over schools of these NPS teachers, are highly unlikely to have more than 0 to 4 years of experience. Charter teachers are more than 3x as likely to have 0 to 4 years as opposed to 6 to 9 years, 10 times as likely to have 0 to 4 years as opposed to 10 to 14 years, 20 times as likely to have 0 to 4 years as opposed to 15 to 19 years, and nearly 100 times as likely to have 0 to 4 years of experience than to have more than 19 years of experience.

The overall effect of One Newark on the total Newark teaching corps may likely be to make it more white and less experienced than it is currently.

We find patterns of racial bias in the consequences to staff similar to those we found in the consequences to students, largely because the racial profiles of students and staff within the NPS schools are correlated. In other words: Newark’s black teachers tend to teach the district’s black students; therefore, because One Newark disproportionately affects those black students, black teachers are more likely to face an employment consequence.

NPS’s black teachers are also more likely to have positions in the schools that are designated by the state as needing interventions – the more challenging school assignments. The schools of NPS black teachers consequently lag in proficiency rates, but not in student growth. We do not know the dynamics that lead to more black teachers being assigned to these schools; qualitative research on this question is likely needed to understand this phenomenon.

One Newark will turn management of more NPS schools over to charter management organizations. In our previous brief, we questioned the logic of this strategy, as these CMOs currently run schools that do not teach students with similar characteristics to NPS’s neighborhood schools. Evidence suggests these charters would not achieve any better outcomes with this different student population.

This brief adds a new consideration to the shift from traditional public schools to charters: if the CMOs maintain their current teaching corps’ profile in an expansion, Newark’s teachers are likely to become more white and less experienced overall. Given the importance of teacher experience, particular in the first few years of work, Newark’s students would likely face a decline in teacher quality as more students enroll in charters.

The potential change in the racial composition of the Newark teaching corps under One Newark – to a staff that has a smaller proportion of teachers of color – would occur within a historical context of established patterns of discrimination against black teachers. “Choice” plans in education have previously been found to disproportionately impact the employment of black teachers; One Newark continues in this tradition. NPS may be vulnerable to a disparate impact legal challenge on the grounds that black teachers will disproportionately face employment consequences under a plan that arbitrarily targets their schools.

And now to editorialize in no uncertain terms…

One Newark is an ill-conceived plan. It is simply wrong, statistically, conceptually and quite possibly legally. That it can be so wrong on so many levels displays an astounding combination of ignorance and arrogance among its designers, promoters and supporters.

First, the justifications for school closures are, well, unjustified. The data said to support the plan simply don’t. Even if closing schools based on poor performance could be justified, the data do not indicate a valid performance based reason for the selections. This is either a sign of gross statistical incompetence on the part of district (and by extension, state) officials or evidence that they have made their decisions on some other basis entirely.

Second, the fact that in many cases, lower performing charters are slated to takeover higher performing district schools (when accounting for students served) is utterly ridiculous. Again, this is either evidence of gross statistical malfeasance and complete ignorance on the part of district officials or that their choices are based on something else entirely. Certainly it is a clever strategy for making charters look good to assign them to takeover schools that already outperform them. But I suspect I’m giving district officials too much credit if I assume this to be their rationale.

Third and finally, if I heard someone suggest 10 years ago [in a time when data free ideological punditry was at least somewhat more moderated and history marginally more understood and respected], that we should start reforming Newark or any racially mixed urban district by closing the black schools, firing the black teachers, selling their buildings and turning over their management to private companies (that may ignore many student and employee rights), I’d have thought they were either kidding or members of some crazy extremist organization [Note that this plan is substantively different in many ways from the Philadelphia privatization plan that was adopted over ten years ago, where private companies held contracts with the district, and thus remained under district governance].

It would be one thing if there were valid facilities utilization, safety or health concerns and other legitimate reorganization considerations that just so happened to affect a larger share of black than other students and teachers. It is difficult if not impossible to protect against any and all racially disparate effects, even when making well-reasoned, empirically justifiable policy decisions.

But this proposed plan, as shown in our analyses, is based on nothing, nor has there been any real, thoughtful or statistically reasonable attempt to justify that it is actually based on something. No legitimate data analyses have been provided to support the plan (much like the flimsy parallel proposal in Kansas City).

It is truly a sad commentary on the state of the education reform conversation that we would even entertain the One Newark proposal, and even more so that we would entertain such a proposal with no valid justification and an increasing body of evidence to the contrary.