A Two-Year Plan for Reforming Florida Public Education Finance & Governance

In a recent report on public education in Florida, I made the following recommendations:[1]

- Recommendation 1 –Financing a Uniform System of High Quality Public Schools

- Phase 1: Engage in the work of setting a manageable standard of “high quality” public schooling for Florida’s children by engaging in analyses of the costs associated with providing each and every child in Florida with equal educational opportunity to achieve high education outcomes.

- Establish a statewide commission on school funding.

- Engage stakeholders in setting standards of excellence for Florida children.

- Engage experts to estimate the costs associated with meeting those standards, applying appropriately rigorous methods.

- Phase 2: Guided by those estimates, reform the school finance formula and increase state aid to schools so as to provide them with the necessary resources for all children to have equal educational opportunity to achieve high education outcomes. That is, meet the constitutional standard ratified by Florida voters in 1998 and 2002. This should include estimates of commensurate funding for charter schools, based on needs and costs.

- Take eliminating or reducing property taxes off the table. The most effective form of property tax relief is increased state aid, as would occur under implementation of this recommendation.

- Recommendation 2 – Charter School Reset

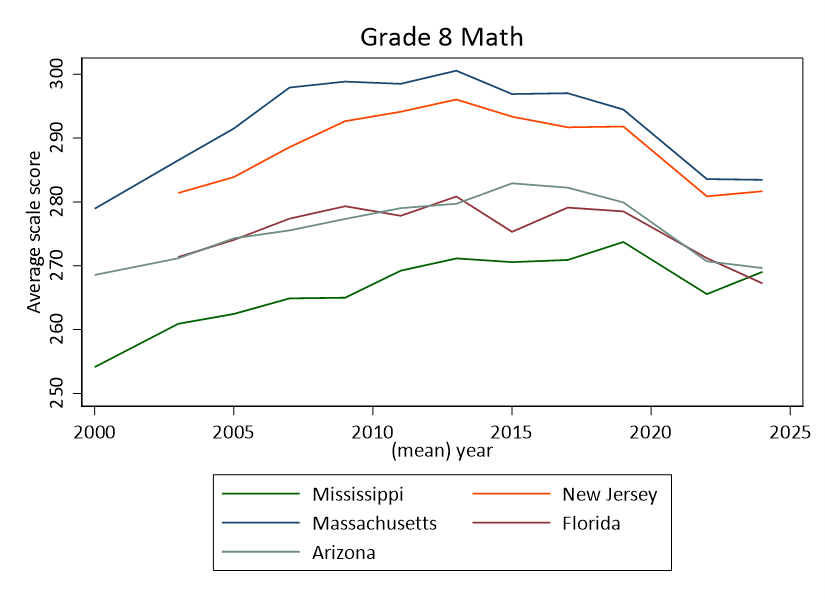

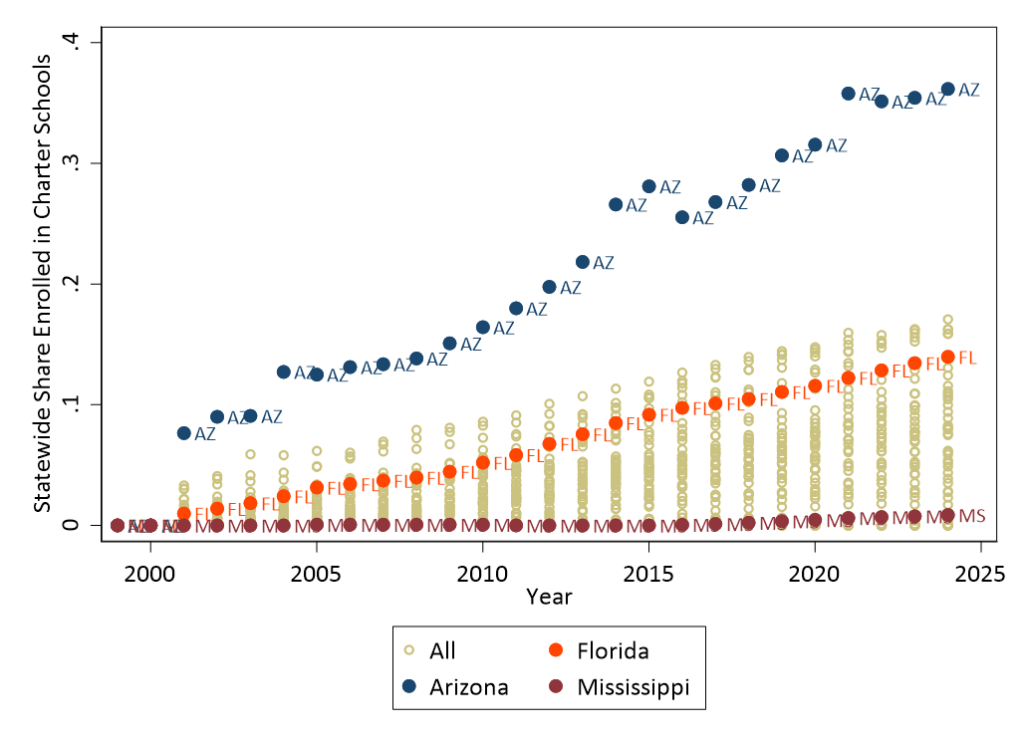

- Part 1: Impose a moratorium on charter school expansion, including the Schools of Hope Program. The existing charter school sector in Florida is compromising equity, eroding efficiency and producing poor educational outcomes for those it serves.

- Part 2: Establish new regulations for evaluating existing charter operators and vetting new charter operators to ensure improved equity in the distribution of students by their needs across schools. Adopt and enforce stricter regulations pertaining to student outcomes.

- Part 3: Adopt updated charter school legislation to ensure that charter schools are sufficiently “public,” required to operate as if “state actors,” protecting children’s constitutional rights and abiding by all relevant federal statutes.

- Recommendation 3 – Voucher Freeze & Reallocate

- Freeze expansion of the voucher program to free up state resources to support a fully funded, overhauled public school finance formula, to provide a uniform system of free public schools.

The justification for each of these recommendations is thoroughly documented in the cited report. The next step is to lay out an action plan for policy advocacy for the next two years, and next two Florida legislative cycles.

Two year Plan

Following are my recommendations for that two -year action plan:

Year 1 (2026 Session, fy2027) – Pause, Reset & Evaluate

- Repeal and rethink Schools of Hope (SoH)

The Schools of Hope legislation and regulations which have been fast tracked over the past year are an ill-conceived patchwork with little potential to solve systemic problems in Florida public education. But, conversations around that program have revealed three key issues worthy of consideration.

- First, the SoH plan acknowledges that Florida’s existing charter sector is not strong and that recruiting proven providers from other states might be necessary.

- Second, the SoH plan includes substantial additional funding (nearly $5k) per pupil to ensure that designated schools could be successful.

- Third, the SoH plan acknowledges the importance of and costs related to operations and maintenance of capital – land and buildings needed for providing quality education.

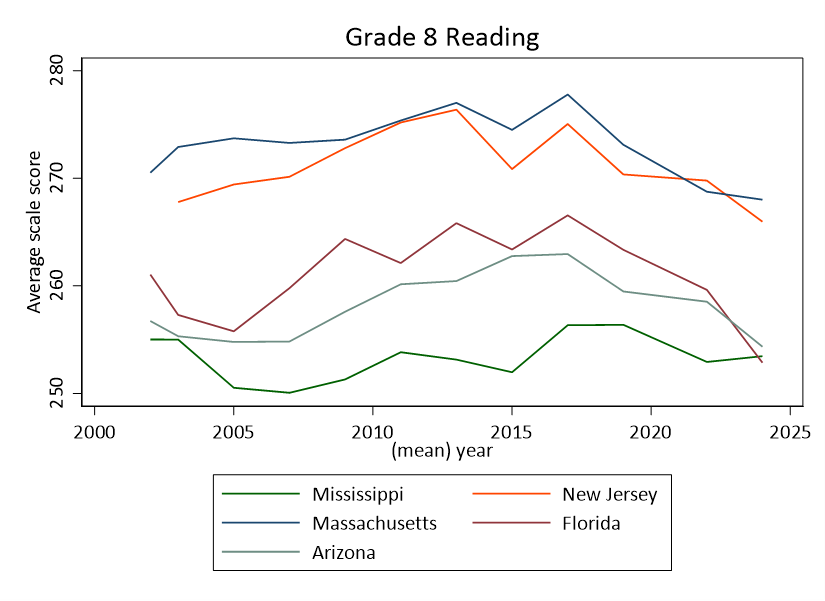

Presumptively, a taxpayer financed school of choice shouldn’t exist to begin with unless it provides some element of “hope.” Hope for better student academic outcomes, while maintaining children’s and taxpayers’ rights. Empirical evidence in my report indicates that the charter sector on average in Florida, does not advance “hope” for better academic outcomes for Florida’s children. The purported need to create a special class of charter schools (ones that do offer “hope”), requiring access to free capital and substantial additional funding in order to be “successful” is indicative of the systemic problem state legislators have failed to address.

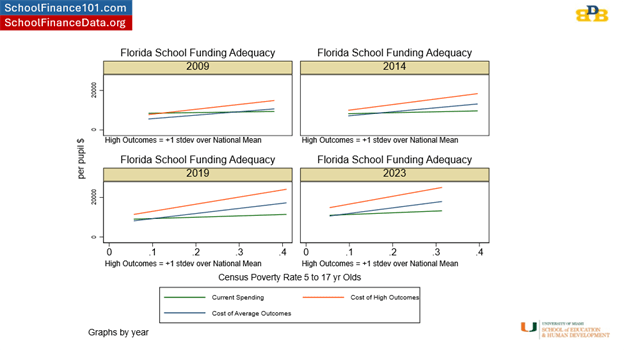

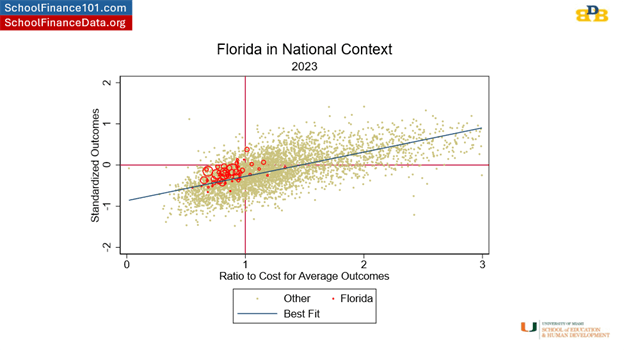

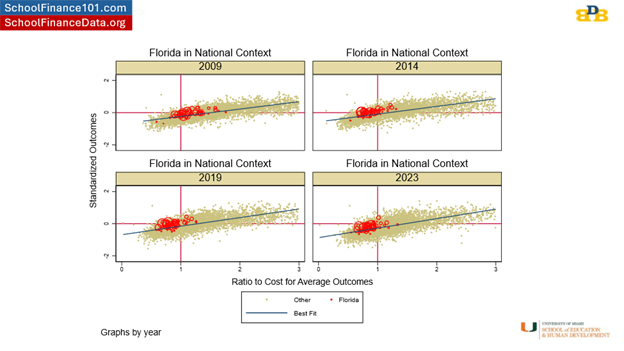

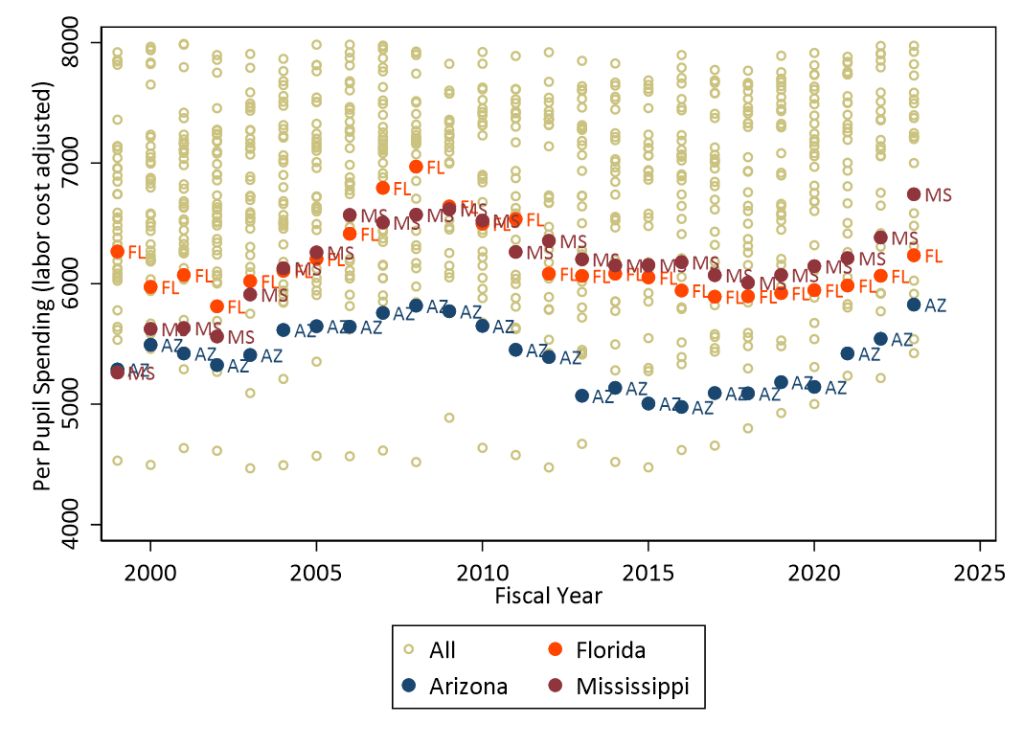

My report explains that Florida public schools, inclusive of charter schools lack the funding needed to achieve high performance. Still, they perform quite efficiently with the funding they have. Florida public district AND charter schools would benefit from that same boost in funding (approximately 50% increase to annual operating expenditures). But the proposed SoH plan instead, taps into the operating expenses of district schools to offset costs for charter schools (for operations and maintenance of facilities), giving district officials little control over that allocation, while also boosting revenues for designated SoH charter operators. This plan is grossly inequitable, applying non-uniform treatment across schools and usurping constitutional authority of local boards of education to efficiently operate a system of high-quality schools. The plan as currently proposed must be repealed.

- Revisit charter schools and charter sector statutes and regulations

The U.S. Supreme Court may soon rule that charter schools under most state charter school laws do not operate as “state actors” and thus are not compelled recognize children’s constitutional rights to free speech, free exercise of religion, due process in cases of disciplinary action, or equal protection. Thus, it will fall on states to rewrite their charter school legislation to ensure that the protections available to children in charter schools are equal to those attending public district schools.[2]

A second issue that must be addressed is the evaluation of a) current charter operators and their reauthorization and b) the vetting of potential outside providers. The state must tighten statutory and regulatory requirements – and apply existing ones – to ensure that providers of schools of choice are a) not having detrimental economic or demographic segregative impact on local neighborhoods and schools and b) are provided quality education as measured by relevant outcomes compared against schools serving similar student populations and with equitable resources. Outside providers wishing to be authorized should validate that they have been successful serving a representative population with respect to the spaces in which they plan to operate locally.

A third issue that must be addressed is the equitable distribution of and cost-sharing for capital space. The SoH plan essentially provides squatters rights to recognized charter operators and then pushes the costs onto local districts. My previous writings have asserted that it may be reasonable to provide access to publicly owned and maintained capital for charter operators, rather than have them use tax dollars to acquire land and buildings for private ownership.[3] Publicly owned and operated schools are governed under the constitutional authority (in Florida) of local boards of education. The state may develop guidance for local boards of education to collaborate with charter operators for access to under-used district capital. Local boards can/should submit plans for such collaboration. This approach is favorable over selling those assets to affiliates of charter operators via 3rd party transactions wherein tax dollars are used to buy – via revenue bond debt, a facility that the public owns – and after buying that facility a second time, the public no longer owns it.[4]

A fourth issue is the equitable financing of district and charter schools according to reasonable estimates of the costs associated with differences in student populations served, and with separate consideration of equitable cost sharing for capital space. On the first, point, a study conducted for the State of Maryland provides insights on the complexities of “commensurate” funding (e.g. “uniform” in a Florida context) for district and charter schools. [5]

A final issue that must be addressed is transparency and thoroughness of financial reporting including reporting on and regulation of related party transactions of contractual services and for capital acquisition.[6] The latter can be mitigated by public oversight of access to publicly owned capital. Recent reporting by CBS News exposed the complex web of financial relationships between charter management companies and contracted service providers, most of which under current law, remain permissible, however suspect and opaque.[7] These issues can be fixed.[8]

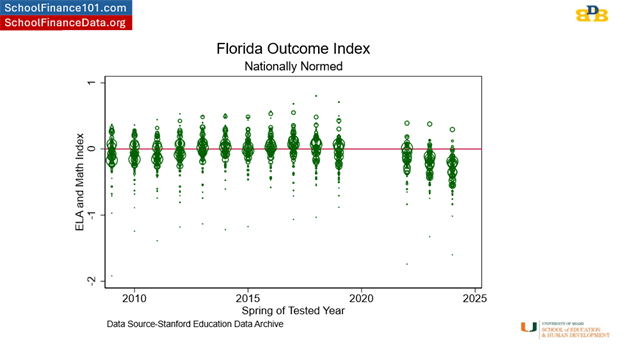

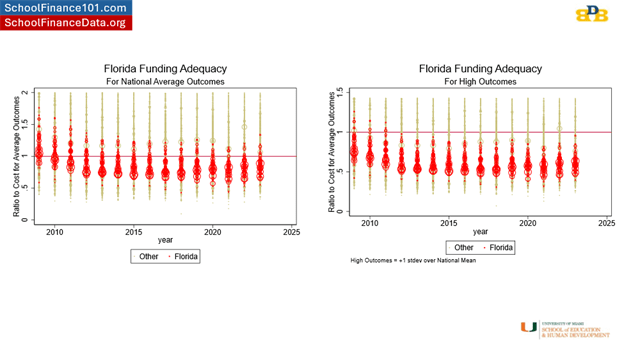

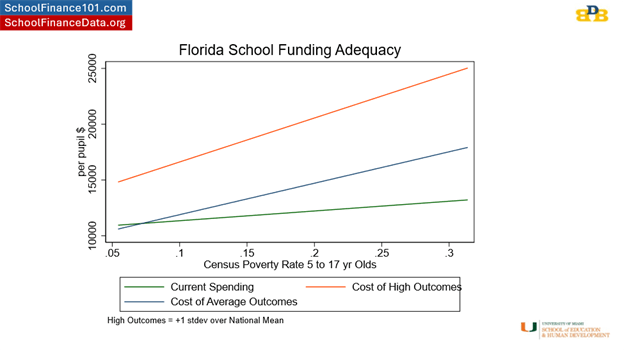

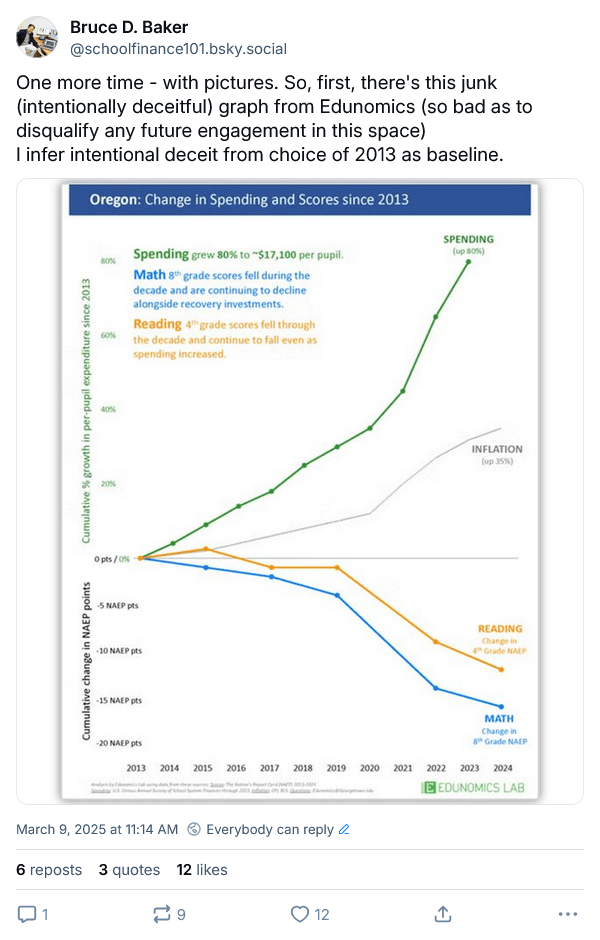

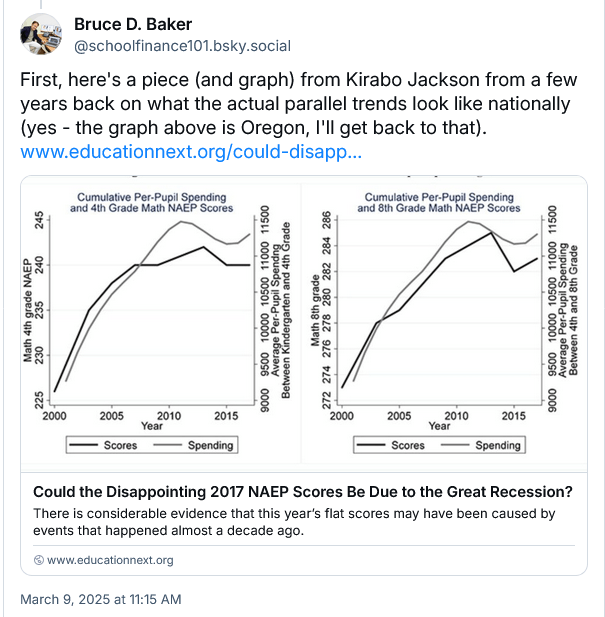

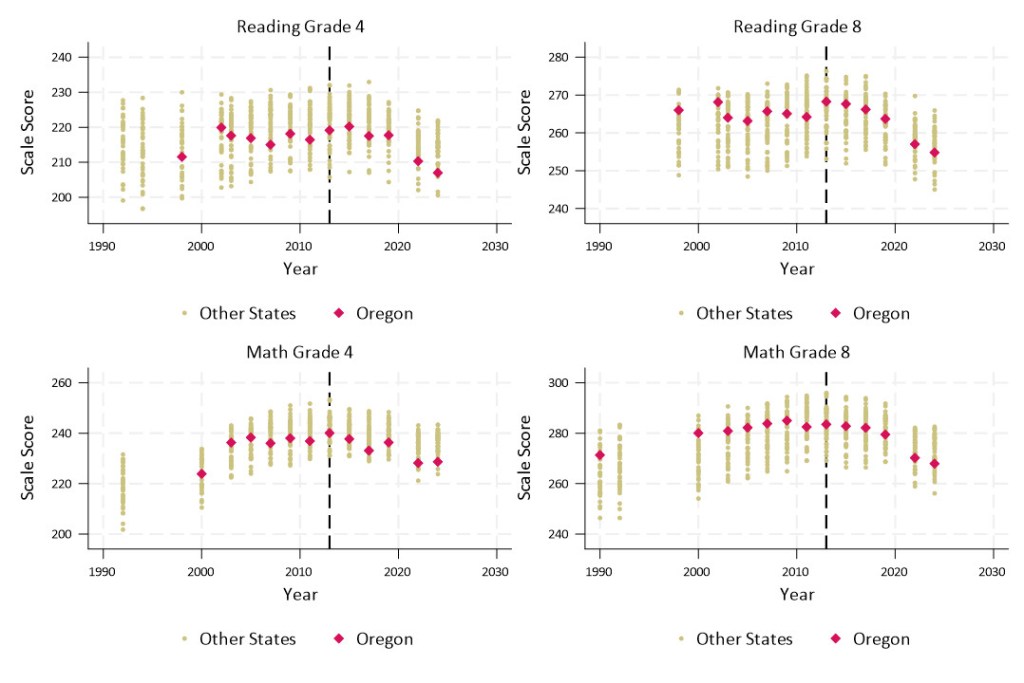

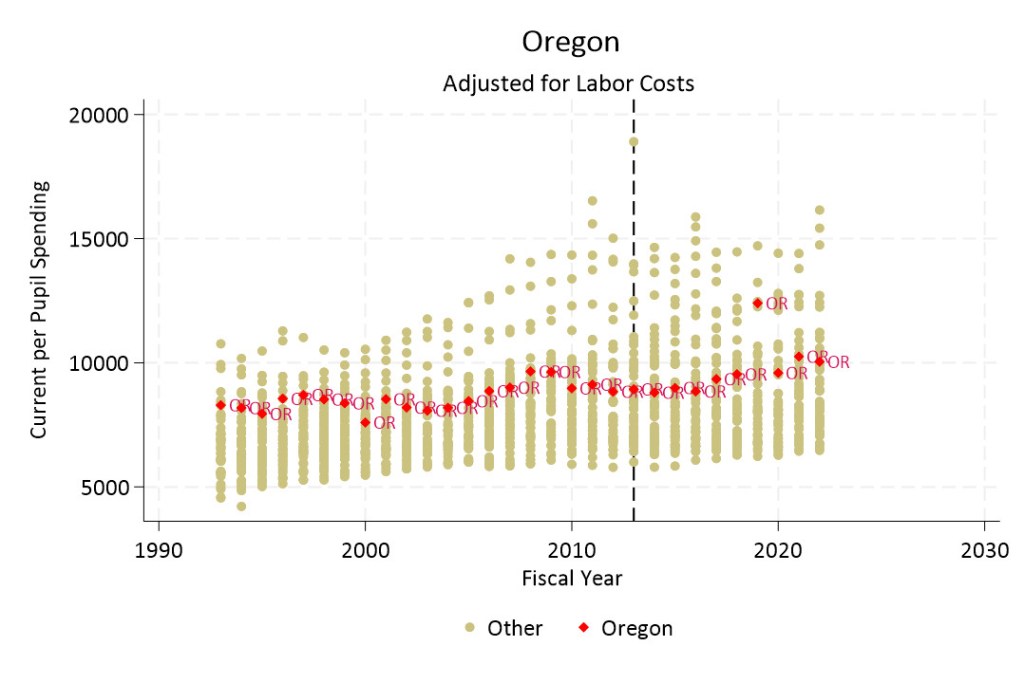

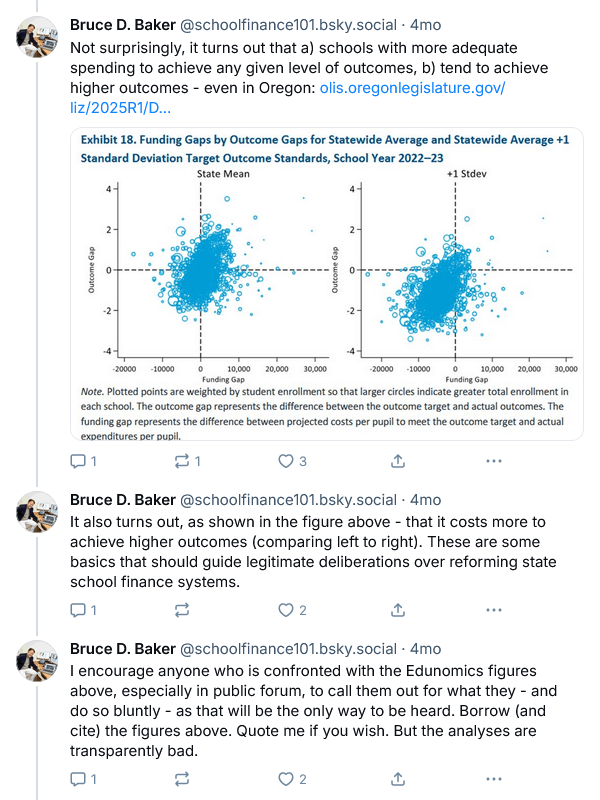

- Equal Opportunity for High Quality Schooling Commission

The tacit acknowledgment in the SoH proposal that schools in Florida need more money – a lot more money – if we expect them to succeed, at high levels, while serving the state’s most disadvantaged communities – is a good starting point. As I noted in my report, funding matters for the quality of student outcomes that can be achieved. [9] Funding matters more in higher poverty, previously lower spending settings. Further, well designed state school finance policies are guided by outcome goals, wherein funding levels are calibrated with respect to the costs to achieve the desired outcome goals. Those costs vary across children and settings, to achieve comparable outcome goals.[10]

The legislature should establish commission and engage the public in setting those goals and then working with qualified experts in determining the costs to achieve those goals across children and educational settings in Florida. Those analyses may guide a comprehensive reform of school funding for Year 2 of this plan.

The back of the napkin spending increases proposed for Schools of Hope may be a useful guidepost for year 1 increases for the state’s highest poverty schools and districts, where those increases are just under $5,000 per pupil. Figure 26 of my report shows that if the state were to recapture even 70% of the budgeted school voucher funds for the current year, per pupil funding could be increased by just under $5,000 per pupil for the highest poverty quintile of school districts and $2,000 per pupil in the second highest poverty quintile. Per the relevant research on return on investment of education spending, this would be a far more productive and efficient allocation of those same dollars. District and charter schools would equally/uniformly benefit.

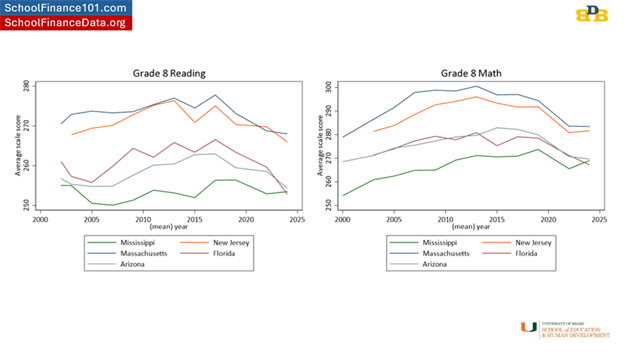

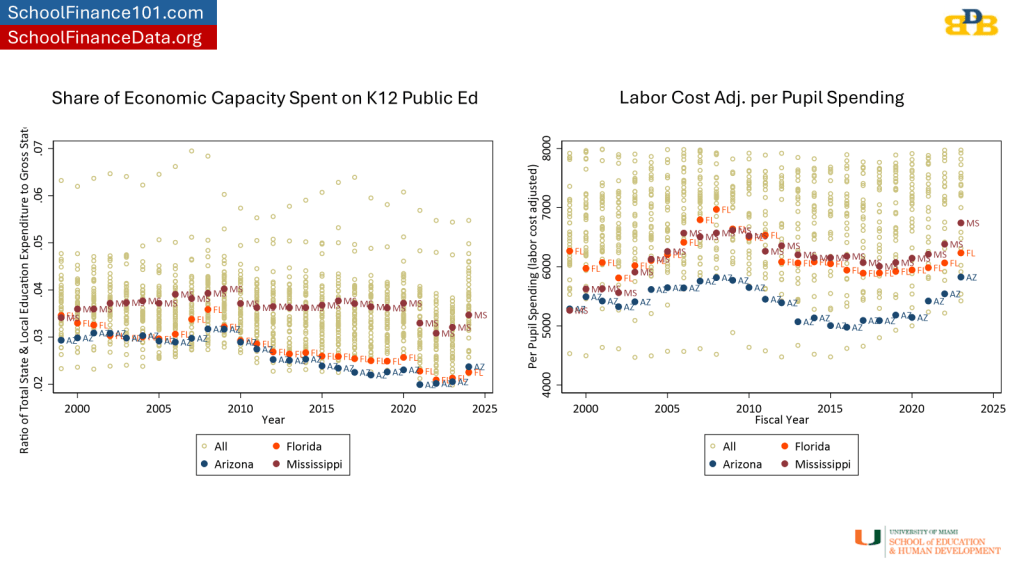

- Resist any and all reductions or limitations on major tax revenue sources

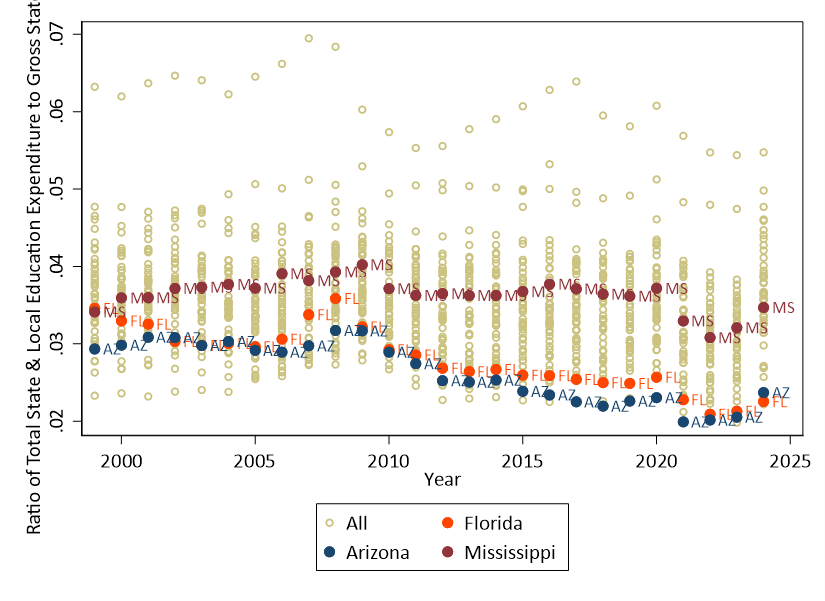

On average, tax and expenditure limits have long run detrimental effects on public service quality including the quality of public schooling measured by students’ outcomes or by the quality of inputs to schooling including class sizes and teacher compensation.[11] Florida district and charter schools are already suffering a lack of sufficient funding to produce high outcomes. As illustrated in my report, Florida’s local public school districts are highly efficient at producing outcomes with the resources available.

At the same time, Florida school districts have become more dependent on local property tax revenues to maintain current levels of service. While the share of revenue from property taxes has increased over the past 30 years, current spending per pupil has remained stagnant. Eliminating, cutting or capping property taxes either inclusive of school property taxes or not will place undue strain on local county and municipal budgets that will either directly or indirectly squeeze public and charter school resources for both operations and capital. The appropriate approach would be for the state to identify new tax revenue sources and use those sources to increase state aid to municipalities and school districts, taking pressure off local property taxes. State aid is the best form of property tax relief, permitting the services to be provided at the level of quality desired with less burden on local taxation to cover the costs of those services.[12]

Year 2 (2027 Session, fy2028) – Overhaul School Funding Formula & related Governance

- Overhaul (replace) the School Finance Formula

Adopt a comprehensive school finance formula designed to cover all annual operating costs of schools, with the exception of transportation and capital. That school finance formula, unlike the present formula, should be calibrated to ensure that every district and school statewide has the resources necessary for all children to have equal opportunity to achieve the desired outcomes (as vetted through the public engagement process in year 1).

- That formula must include appropriate adjustments for the costs of serving children from different backgrounds and attending school across different settings. This includes but may not be limited to a) children from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, b) English learners, c) children with disabilities. Geographic and location factors should include but may not be limited to a) very small schools in remote, sparsely populated locations, b) differences in labor costs (associated with recruiting/retaining teachers of comparable qualifications across locations).

- That formula should be inclusive of uniform funding for charter schooling, with potential exclusions (or charges applied) for services provided to charter students through the host district.

- Separate, equitable formulas must be developed for a) the financing and allocation of capital (educational spaces) for district and charter enrolled students, and b) the financing centralized planning of transportation services.

- Phase down (and out) funding of any new cohorts of voucher students

This should free up substantial resources to support the first recommendation above, but additional revenues will likely still be needed.

- Reorganize/reconstitute charter operators that do not contribute positively to equity or efficiency

Florida has far too many charter operators that underserve children with disabilities, English learners and children from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, and yield poor academic outcomes for those they do serve when compared to district regular and magnet schools serving similar student populations.

Using policy tools (legislation and regulations) developed in year 1, the state should begin the process of reconstituting these schools. Decisions should be based both on whether a school (or operator of many schools) contributes to or erodes equity with respect to students served versus those served in surrounding schools and residing in surrounding neighborhoods, in addition to performance metrics based on the population served. Any changes to or closures of schools should consider the least disruptive option for those currently enrolled.

NOTES

[1]Baker, B.D. (2025) Financing a High-Quality System of Free Public Schools for Florida’s Children https://schoolfinance101.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/florida_school_finance_12.02.25.pdf

[2] Green III, P. C., & Eckes, S. E. (2024). All Aboard!: Making Charter School Boards All-Purpose State Actors under the Supreme Court’s Amtrak Case. Drake L. Rev., 71, 562.

[3] Baker, B. D. (2016). Exploring the Consequences of Charter School Expansion in US Cities. Economic Policy Institute. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED588750.pdf

Baker, B., & Miron, G. (2015). The Business of Charter Schooling: Understanding the Policies That Charter Operators Use for Financial Benefit. National Education Policy Center. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED574733.pdf

[4] Baker, B.D. (2015) We bought it twice but we nolonger own it. School Finance 101. https://schoolfinance101.com/2015/07/21/we-bought-it-twice-but-we-no-longer-own-it-is-co-location-the-better-option/

[5] Levin, J., Baker, B., Atchison, D., Brodziak, I., Boyle, A., Hall, A., & Becker, J. (2016). Study of funding provided to public schools and public charter schools in Maryland. American Institutes for Research. https://marylandpublicschools.org/stateboard/Documents/01242017/TabG-CharterPublicSchoolFundingStudy.pdf

[6] Green III, P. C., Baker, B. D., & Oluwole, J. O. (2018). Are charter schools the second coming of Enron: An examination of the gatekeepers that protect against dangerous related-party transactions in the charter school sector. Ind. LJ, 93, 1121.

[7] https://www.cbsnews.com/video/florida-charter-school-company-gop-figure-parents-frustrated/

[8] https://theconversation.com/charter-schools-exploit-lucrative-loophole-that-would-be-easy-to-close-111792

[9] Baker, B. D., & Knight, D. (2025). Does money matter in education? Albert Shanker Institute. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED671888.pdf

[10]Atchison, D., Levin, S., Levin, J., Kolar, A., Blair, D., Srikanth, A., & Salvato, B. (2024). Equity and Adequacy of Colorado School Funding: A Cost-Modeling Approach. https://www.cde.state.co.us/cdedepcom/schoolfinancecostmodelingadequacystudyreport

D. Atchison, B.D. Baker, J. Levin, S. Fatima, A. Trauth, A. Srikanth, C. Herberle, N. Gannon-Slater, L. Junk, K., Wallace, L., & Baker, B. (2023) Assessment of Delaware Public School Funding. https://education.delaware.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/23-22933_1_Delaware_Full_Report-FMT-ed103023-Version-2.pdf

Atchison, D., Baker, B.D., Levin, J., Kearns, C. (2020) New Hampshire Commission to Study School Funding, Final Report. https://carsey.unh.edu/sites/default/files/media/2020/09/20-12685_nh_final_report_v10.pdf

Brooks, C., Levin, J., Baker, B., & Salvato, B. (2025). Understanding the Cost of Providing Adequate Educational Opportunity in Oregon. https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2025R1/Downloads/CommitteeMeetingDocument/291280

[11] Downes, T. A., & Figlio, D. N. (2012). Tax and expenditure limits, school finance and school quality. In Handbook of research in education finance and policy (pp. 395-410). Routledge.

[12] Baker, B. D., Di Carlo, M., & Oberfield, Z. W. (2023). The Source Code: Revenue Composition and the Adequacy, Equity, and Stability of K-12 School Spending. Albert Shanker Institute.