Please also see follow-up discussion here: https://schoolfinance101.wordpress.com/2012/01/19/follow-up-on-fire-first-ask-questions-later/

Yesterday was a big day for big new studies on teacher evaluation. First, there was the New York Times report on the new study by Chetty, Friedman and Rockoff. Second, there was the release of the second part of the Gates Foundation’s Measures of Effective Teaching project.

There’s still much to digest. But here’s my first shot, based on first impressions of these two studies (with very little attention to the Gates study)

The second – Gates MET study – didn’t have a whole lot of punchline to it, but rather spent a great deal of time exploring alternative approaches to teacher evaluation and the correlates of those approaches to a) each other and b) measured student outcome gains. The headline that emerged from that study, in the Washington Post and in brief radio blurbs was that teachers ought to be evaluated by multiple methods and should certainly be evaluated more than once a year or every few years with a single observation. That’s certainly a reasonable headline and reasonable set of assertions. Though, in reality, after reading the fully study, I’m not convinced that the study validates the usefulness of the alternative evaluation methods other than that they are marginally correlated with one another and to some extent with student achievement gains, or that the study tells us much if anything about what schools should do with the evaluation information to improve instruction and teaching effectiveness. I have a few (really just one for now) nitpicky concerns regarding the presentation of this study which I will address at the end of this post.

The BIG STUDY of the day… with BIG findings … at least in terms of news headline fodder, was the Chetty, Friedman & Rockoff (CFR) study. For this study, the authors compile a massive freakin’ data set for tech-data-statistics geeks to salivate over. The authors used data back to the early 1990s on children in a large urban school district, including a subset of children for whom the authors could gather annual testing data on math and language arts assessments. Yes, the tests changed at different points between 1991 and 2009, and the authors attempt to deal with this by standardizing yearly scores (likely a partial fix at best). The authors use these data to retrospectively estimate value-added scores for those (limited) cases where teachers could be matched to intact classrooms of kids (this would seem to be a relatively small share of teachers in the early years of the data, increasing over time… but still limited to grades 3 to 8 math & language arts). Some available measures of student characteristics also varied over time. The authors take care to include in their value-added model, the full extent of available student characteristics (but remove some later) and also include classroom level factors to try to tease out teacher effects. Those who’ve read my previous posts understand that this is important though quite likely insufficient!

The next big step the authors take is to use IRS tax record data of various types and link it to the student data. IRS data are used to identify earnings, to identify numbers and timing of dependent children (e.g. did an individual 20 years of age claim a 4 year old dependent?) and to identify college enrollment. Let’s be clear what these measures are though. The authors use reported earnings data for individuals in years following when they would have likely completed college (excluding incomes over $100k). The authors determine college attendance from tax records (actually from records filed by colleges/universities) on whether individuals paid tuition or received scholarships. This is a proxy measure – not a direct one. The authors use data on reported dependents & the birth date of the female reporting those dependents to create a proxy for whether the female gave birth as a teenager.[1] Again, a proxy, not direct measure. More later on this one.

Tax data are also used to identify parent characteristics. All of these tax data are matched to student data by applying a thoroughly-documented algorithm based on names, birth dates, etc. to match the IRS filing records to school records (see their Appendix A).

And in the end, after 1) constructing this massive data set[2], 2) retrospectively estimating value-added scores for teachers and 3) determining the extent to which these value added scores are related to other stuff, the authors find…. well… that they are.

The authors find that teacher value added scores in their historical data set vary. No surprise. And they find that those variations are correlated to some extent with “other stuff” including income later in life and having reported dependents for females at a young age. There’s plenty more.

These are interesting findings. It’s a really cool academic study. It’s a freakin’ amazing data set! But these findings cannot be immediately translated into what the headlines have suggested – that immediate use of value-added metrics to reshape the teacher workforce can lift the economy, and increase wages across the board! The headlines and media spin have been dreadfully overstated and deceptive. Other headlines and editorial commentary has been simply ignorant and irresponsible. (No Mr. Moran, this one study did not, does not, cannot negate the vast array of concerns that have been raised about using value-added estimates as blunt, heavily weighted instruments in personnel policy in school systems.)

My 2 Big Points

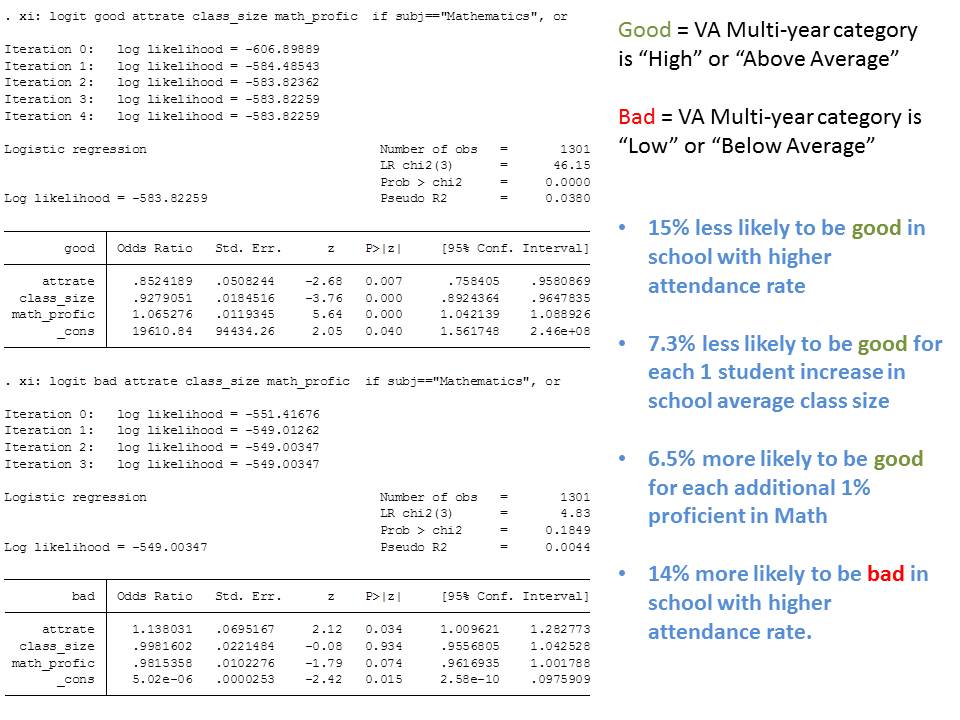

First and perhaps most importantly, just because teacher VA scores in a massive data set show variance does not mean that we can identify with any level of precision or accuracy, which individual teachers (plucking single points from a massive scatterplot) are “good” and which are “bad.” Therein exists one of the major fallacies of moving from large scale econometric analysis to micro level human resource management.

Second, much of the spin has been on the implications of this study for immediate personnel actions. Here, two of the authors of the study bear some responsibility for feeding the media misguided interpretations. As one of the study’s authors noted:

“The message is to fire people sooner rather than later,” Professor Friedman said. (NY Times)

This statement is not justified from what this study actually tested/evaluated and ultimately found. Why? Because this study did not test whether adopting a sweeping policy of statistically based “teacher deselection” would actually lead to increased likelihood of students going to college (a half of one percent increase) or increased lifelong earnings. Rather, this study showed retrospectively that students who happened to be in classrooms that gained more, seemed to have a slightly higher likelihood of going to college and slightly higher annual earnings. From that finding, the authors extrapolate that if we were to simply replace bad teachers with average ones, the lifetime earnings of a classroom full of students would increase by $266k in 2010 dollars. This extrapolation may inform policy or future research, but should not be viewed as an absolute determinant of best immediate policy action.

This statement is equally unjustified:

Professor Chetty acknowledged, “Of course there are going to be mistakes — teachers who get fired who do not deserve to get fired.” But he said that using value-added scores would lead to fewer mistakes, not more. (NY Times)

It is unjustified because the measurement of “fewer mistakes” is not compared against a legitimate, established counterfactual – an actual alternative policy. Fewer mistakes than by what method? Is Chetty arguing that if you measure teacher performance by value-added and then dismiss on the basis of low value-added that you will have selected on the basis of value-added. Really? No kidding! That is, you will have dumped more low value-added teachers than you would have (since you selected on that basis) if you had randomly dumped teachers? That’s not a particularly useful insight if the value-added measures weren’t a good indicator of true teacher effectiveness to begin with. And we don’t know, from this study, if other measures of teacher effectiveness might have been equally correlated with reduced pregnancy, college attendance or earnings.

These two quotes by authors of the study were unnecessary and inappropriate. Perhaps it’s just how NYT spun it… or simply what the reporter latched on to. I’ve been there. But these quotes in my view undermine a study that has a lot of interesting stuff and cool data embedded within.

These quotes are unfortunately illustrative of the most egregiously simpleminded, technocratic, dehumanizing and disturbing thinking about how to “fix” teacher quality.

Laundry list of other stuff…

Now on to my laundry list of what this new study adds and what it doesn’t add to what we presently know about the usefulness of value-added measures for guiding personnel policies in education systems. In other words, which, if any of my previous concerns are resolved by these new findings.

Issue #1: Isolating Teacher Effect from “other” classroom effects (removing “bias”)

The authors do provide some additional useful tests for determining the extent to which bias resulting from the non-random sorting of kids across classrooms might affect teacher ratings. In my view the most compelling additional test involves evaluating the value-added changes that result from teacher moves across classrooms and schools. The authors also take advantage of their linked economic data on parents from tax returns to check for bias. And in their data set, comparing the results of these tests with other tests which involve using lagged scores (Rothstein’s falsification test) the authors appear to find some evidence of bias but in their view, not enough to compromise the teacher ratings. I’m not yet fully convinced, but I’ve got a lot more digging to do. (I find Figure 3, p. 63 quite interesting)

But more importantly, this finding is limited to the data and underlying assessments used by these authors in this analysis in whatever school system was used for the analysis. To their credit, the authors provide not only guidance, but great detail (and share their Stata code) for others to replicate their bias checks on other value added models/results in other contexts.

All of this stuff about bias is really about isolating the teacher effect from the classroom effect and doing so by linking teachers (a classroom level variable) to student assessment data with all of the underlying issues of those data (the test scaling, equating moves from x to x+10 on one test to another, an on one region of the scale on one test to another region of the scale on the same test).

Howard Wainer explains the heroic assumptions necessary to assert a causal effect of teachers on student assessment gains here: http://www.njspotlight.com/ets_video2/

When it comes to linking the teacher value-added estimates to lifelong outcomes like student earnings, or teen pregnancy, the inability to fully isolate teacher effect from classroom effect could mean that this study shows little more than the fact that students clustered in classrooms which do well over time eventually end up less likely to have dependents while in their teens, more likely to go to college (.5%) and earn a few more dollars per week.[3]

These are (or may be) shockingly unsurprising findings.

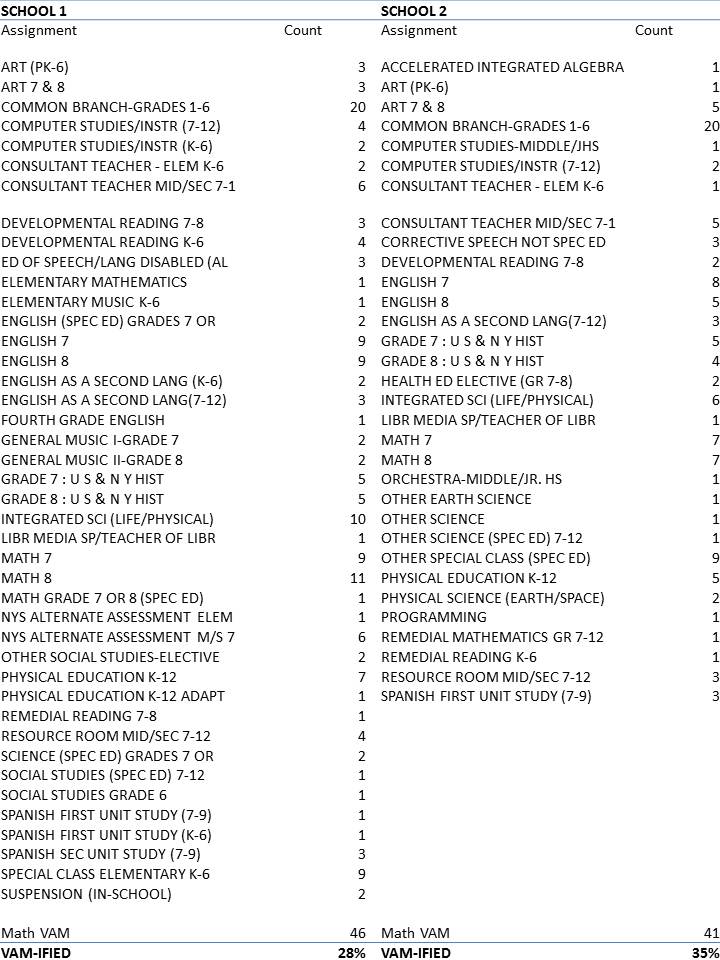

Issue #2. Small Share of Teachers that Can Be Rated

This study does nothing to address the fact that relatively small shares of teachers can be assigned value-added scores. This study, like others merely uses what it can – those teachers in grades 3 to 8 that can be attached to student test scores in math and language arts. More here.

Issue #3: Policy implications/spin from media assume an endless supply of better teachers?

This study like others makes assertions about how great it would all turn out – how many fewer teen girls would get pregnant, how much more money everyone would earn, if we could simply replace all of those bad teachers with average ones, or average ones with really good ones. But, as I noted above, these assertions are all contingent on an endless supply of “better” teachers standing in line to take those jobs. And this assertion is contingent upon there being no adverse effect on teacher supply quality if we were to all of the sudden implement mass deselection policies. The authors did not, nor can they in this analysis, address these complexities. I discuss deselection arguments in more detail in this previous post.

A few final comments on Exaggerations/Manipulations/Clarifications

I’ll close with a few things I found particularly annoying:

- Use of super-multiplicative-aggregation to achieve a number that seems really, really freakin’ important (like it could save the economy!).

One of the big quotes in the New York Times article is that “Replacing a poor teacher with an average one would raise a single classroom’s lifetime earnings by about $266,000, the economists estimate.” This comes straight from the research paper. BUT… let’s break that down. It’s a whole classroom of kids. Let’s say… for rounding purposes, 26.6 kids if this is a large urban district like NYC. Let’s say we’re talking about earnings careers from age 25 to 65 or about 40 years. So, 266,000/26.6 = 10,000 lifetime additional earnings per individual. Hmmm… nolonger catchy headline stuff. Now, per year? 10,000/40 = 250. Yep, about $250 per year (In constant, 2010 [I believe] dollars which does mean it’s a higher total over time, as the value of the dollar declines when adjusted for inflation). And that is about what the NYT Graph shows: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2012/01/06/us/benefits-of-good-teachers.html?ref=education

- The super-elastic, super-extra-stretchy Y axis

Yeah… the NYT graph shows an increase of annual income from about $20,750 to $21,000. But, they do the usual news reporting strategy of having the Y axis go only from $20,250 to $21,250… so the $250 increase looks like a big jump upward. That said, the author’s own Figure 6 in the working paper does much the same!

- Discussion/presentation of “proxy” measure as true measure (by way of convenient language use)

Many have pounced on the finding that having higher value added teachers reduces teen pregnancy and many have asked – okay… how did they get the data to show that? I explained above that they used a proxy measure based on the age of the female filer and the existence of dependents. It’s a proxy and likely an imperfect one. But pretty clever. That said, in my view I’d rather that the authors say throughout “reported dependents at a young age” (or specific age) rather than “teen pregnancy.” While clever, and likely useful, it seems a bit of a stretch, and more accurate language would avoid the confusion. But again, that doesn’t generate headlines.

- Gates study gaming of stability correlations

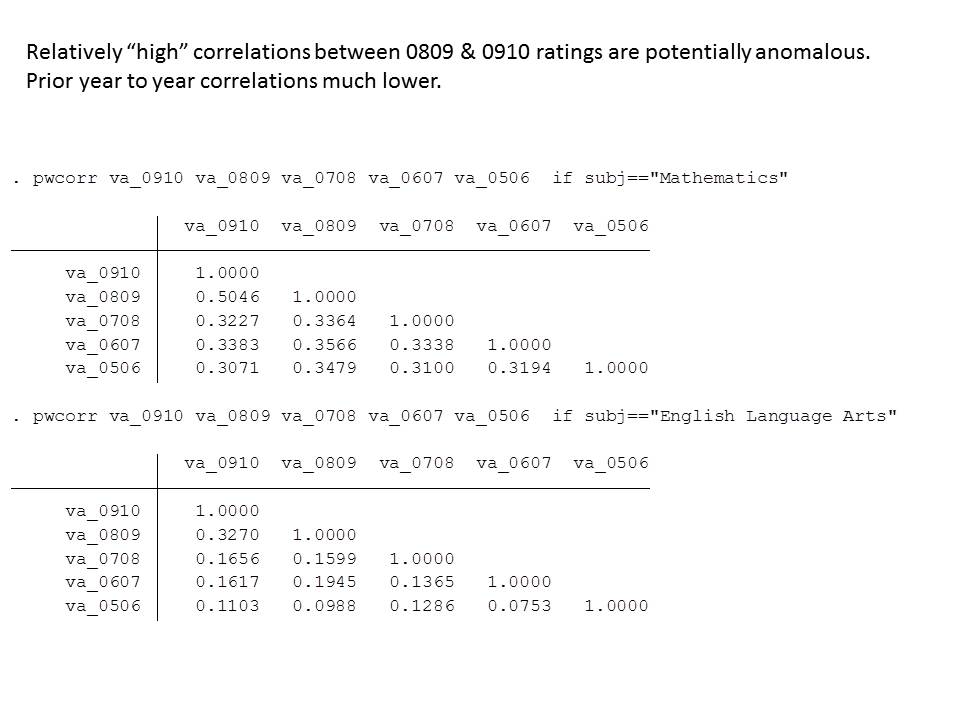

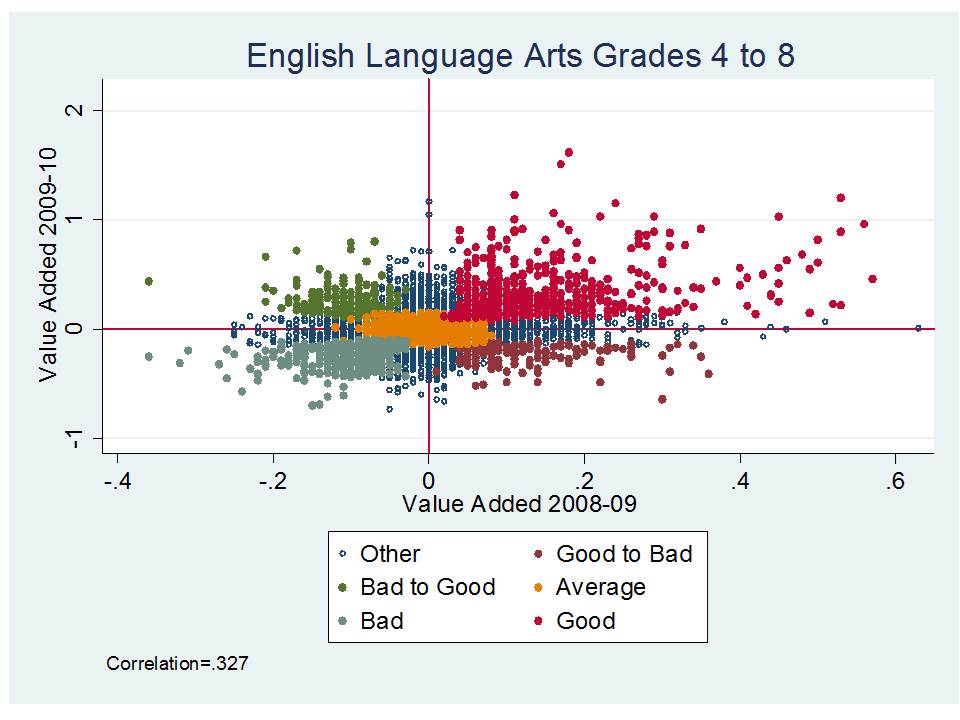

I’ve spent my time here on the GFR paper and pretty much ignored the Gates study. It didn’t have those really catchy findings or big headlines. And that’s actually a good thing. I did find one thing in the Gates study that irked me (I may find more on further reading). In a section starting on Page 39 the report acknowledges that a common concern about using value-added models to rate teachers is the year volatility of the effectiveness ratings. That volatility is often displayed with correlations between teachers’ scores in one year and the same teachers’ scores the next year, or across different sections of classes in the same year. Typically these correlations have fallen between .15 and .5 (.2 and .48 in previous MET study). These low correlations mean that it’s hard to pin down from year to year, who really is a high or low value added teacher. The previous MET report made a big deal of identifying the “persistent effect” of teachers, an attempt to ignore the noise (something which in practical terms can’t be ignored), and they were called out by Jesse Rothstein in this critique: http://nepc.colorado.edu/thinktank/review-learning-about-teaching

The current report doesn’t focus as much on the value-added metrics, but this one section goes to yet another length to boost the correlation and argue that value-added metrics are more stable and useful than they likely are. In this case, the authors propose that instead of looking at the year to year correlations between these annually noisy measures, we should correlate any given year with the teacher’s career long average where that average is a supposed better representation of “true” effectiveness. But this is not an apples to apples comparison to the previous correlations, and is not a measure of “stability.” This is merely a statistical attempt to make one measure in the correlation more stable (not actually more “true” just less noisy by aggregating and averaging over time), and inflate the correlation to make it seem more meaningful/useful. Don’t bother! For teachers with a relatively short track record in a given school, grade level and specific assignment, and schools with many such teachers, this statistical twist has little practical application, especially in the context of annual teacher evaluation and personnel decisions.

[1] “We first identify all women who claim a dependent when filing their taxes at any point before the end of the sample in tax year 2010. We observe dates of birth and death for all dependents and tax filers until the end of 2010 as recorded by the Social Security Administration. We use this information to identify women who ever claim a dependent who was born while the mother was a teenager (between the ages of 13 and 19 as of 12/31 the year the child was born).”

[2] There are 974,686 unique students in our analysis dataset; on average, each student has 6.14 subject-school year observations.

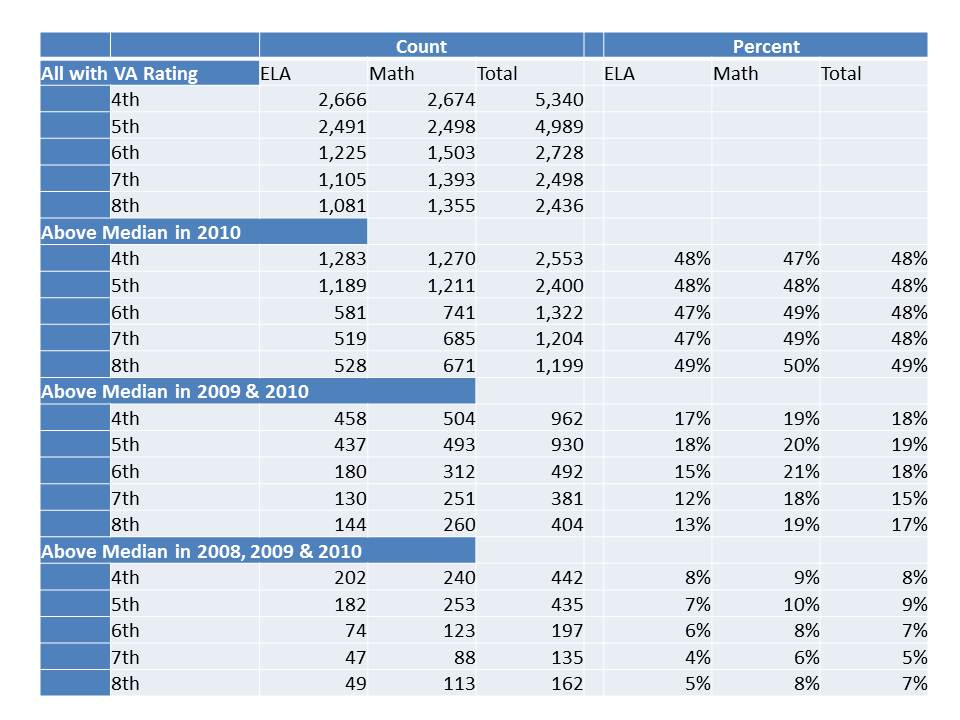

That’s rather depressing isn’t it. The chances of ending up in the bottom third two years in a row are about the same as the chances of ending up in the top half three years in a row!

That’s rather depressing isn’t it. The chances of ending up in the bottom third two years in a row are about the same as the chances of ending up in the top half three years in a row!