UPDATE: As I understand it, NJOSA has now been revised to specifically target Lakewood as a pilot site for the vouchers (1 of 8 locations). Consider the analysis below in that light. This revision potentially allows for a greater share of overall NJOSA funding to flow specifically to Lakewood students. Further, this revision raises fun/interesting legal questions.

Yes, it is true that the Zelman case found that the Cleveland voucher program did not violate the establishment clause of the first amendment by providing vouchers to children who in large numbers chose to attend religious schools. The court acknowledged that the voucher policy itself was neutral w/respect to religion. However, not too long before Zelman, in Kiryas Joel (NY), the court found that the State of New York had violated the establishment clause when it singled out Kiryas Joel Village in a statute altering the boundaries of local public school districts to specifically serve the exclusively religious community.

So, for example, if a the state of NY were to decide to operate a voucher program, and specifically pilot test that program in Kiryas Joel Village, would such a policy be considered religion neutral, as under Zelman? Or might that policy violate the establishment clause because of the exclusively religious community selected (Kiryas Joel)? Clearly Cleveland (and its private school sector) is far more diverse than Kiryas Joel, providing at least some argument in favor of neutrality. Now, Lakewood is less homogeneous than Kiryas Joel, but clearly more like Kiryas Joel than it is like Cleveland. Thoughts from my legal scholar friends? (consider demographic & pvt. school sector analysis below – written in response to different iteration of NJOSA).

SLIDES: Lakewood Effect Slides

The New Jersey Opportunity Scholarship Act (NJOSA) is being proposed on the basis that $6,000 vouchers for children in grades k-8 and $9000 vouchers for children in grades 9-12 would a) provide much-needed financial relief for financially ailing urban Catholic schools and b) would provide poor and minority children the opportunity to escape chronically under-performing, poor urban New Jersey schools. Implicit in Part B of the claims is that the primary beneficiaries of the voucher program – aside from urban Catholic schools — would be poor and minority children attending so-called “failing” schools in the state’s major urban centers, such as Camden, Newark, Paterson or Jersey City.

I have previously disposed of the first claim – that these vouchers would help financially sustain private schools in New Jersey – here: https://schoolfinance101.wordpress.com/2010/03/23/would-8000-scholarships-help-sustain-nj-private-schools/ Another study that reaches the same conclusion is a 2009 report which found Milwaukee Vouchers are not yielding big financial benefits for the city’s Catholic schools, even where the voucher level exceeded $6,300 in 2005-06 (see: http://www.edexcellence.net/doc/catholic_schools_08.pdf)

But let’s take a closer look at who will really benefit if the New Jersey voucher proposal becomes law. Where are most children in New Jersey already in private school? More specifically, where are most New Jersey children already in private school with a family income low enough (below 250% of the poverty level) to qualify for the NJOSA vouchers? It may seem highly unlikely that many low-income children would already be attending private schools. Indeed, NJOSA is not “intended” to underwrite the education of children already in private schools, but rather to assist children “trapped” in low performing public schools to attend nearby private schools. But, NJOSA includes from the outset a provision that would allow low-income families whose children already attend private schools to access the vouchers, setting aside at least 25% of the total available voucher resources in any given year for such children (as I understand it).

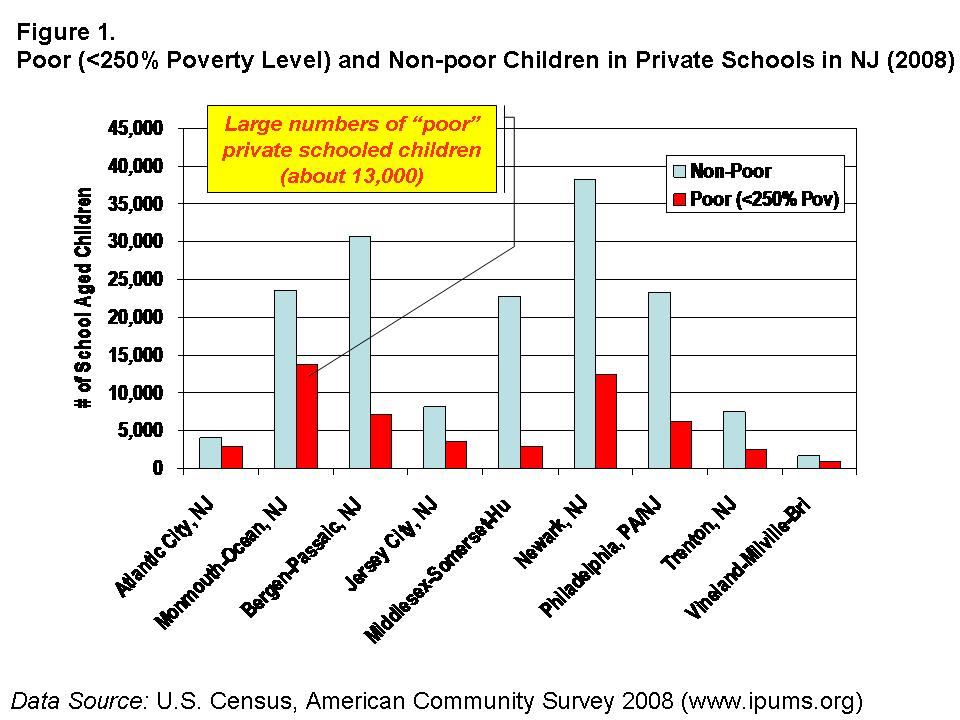

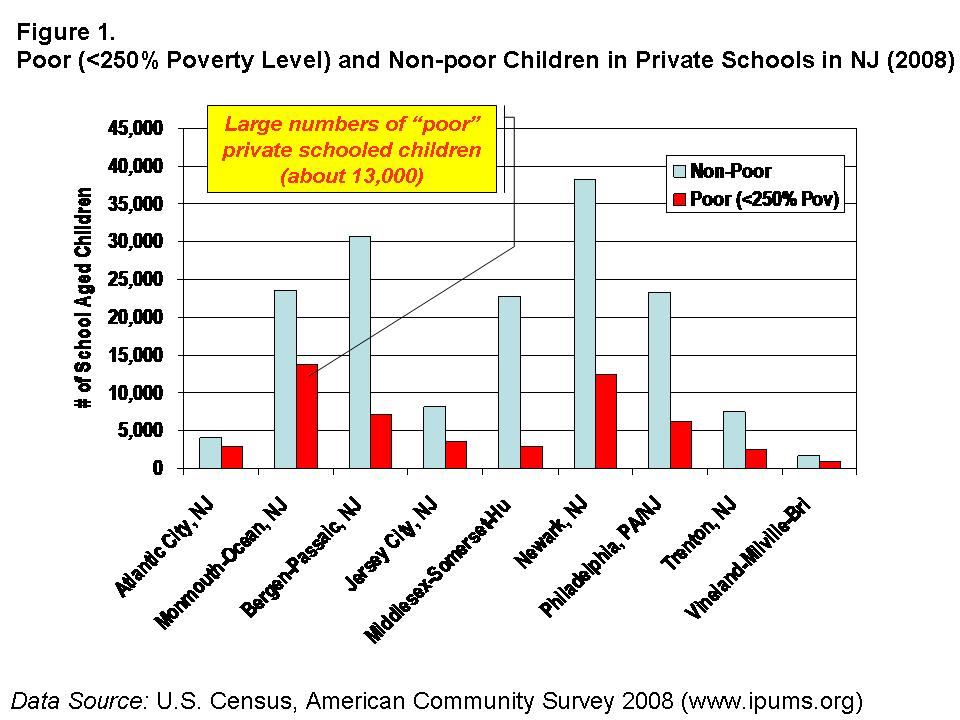

First, where are the largest numbers of private school children in New Jersey?

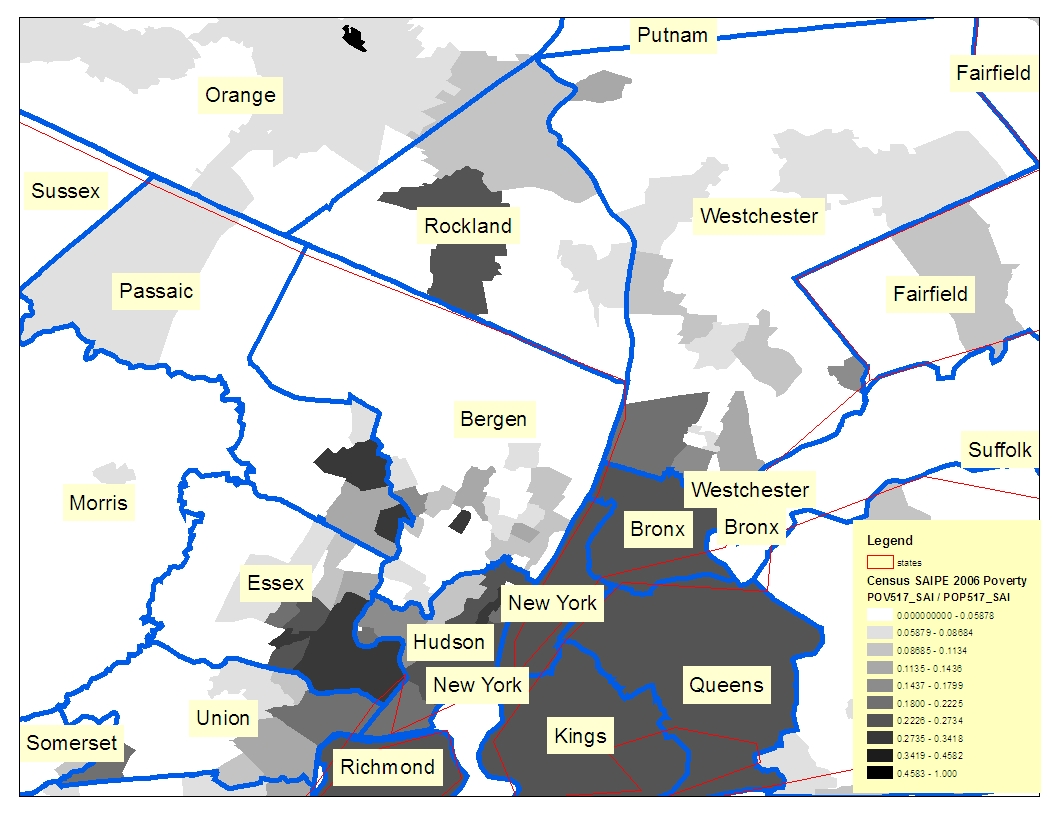

As it turns out, the largest total numbers of privately schooled children are indeed in the Newark area and the second largest number in Bergen-Passaic (combined). The third largest total numbers of private schooled children are in the Lakewood (Ocean County) area. However, when one looks only at those children who would qualify for the NJOSA vouchers, the largest total number are in Lakewood – over 13,000 in 2008. Lakewood has more than Newark, more than Jersey City, and more than anywhere else in New Jersey, despite having much smaller total population. Here are the data:

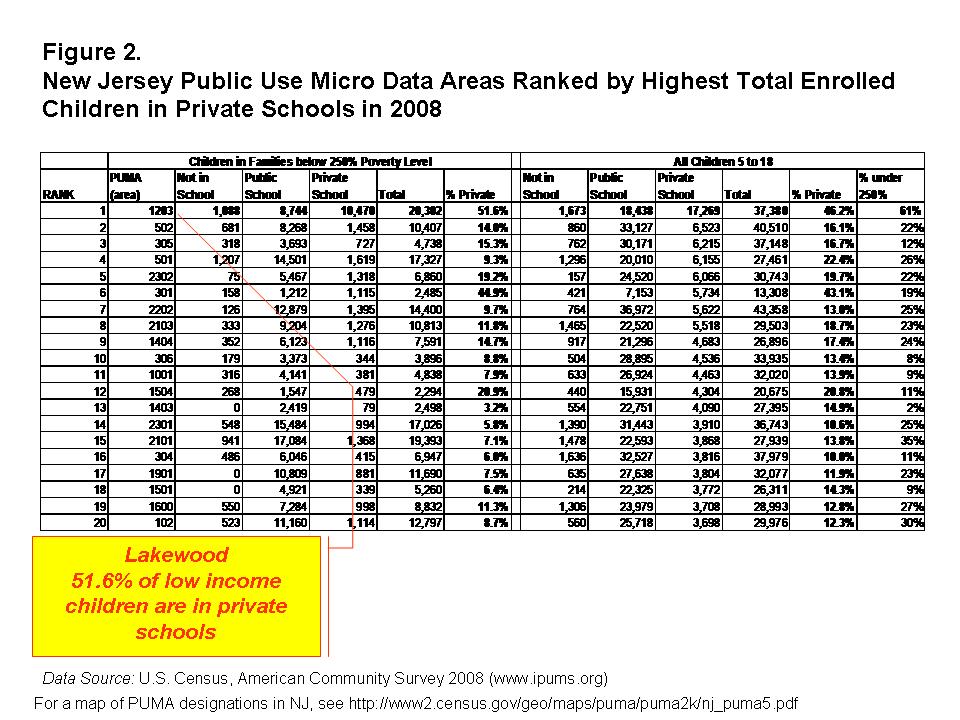

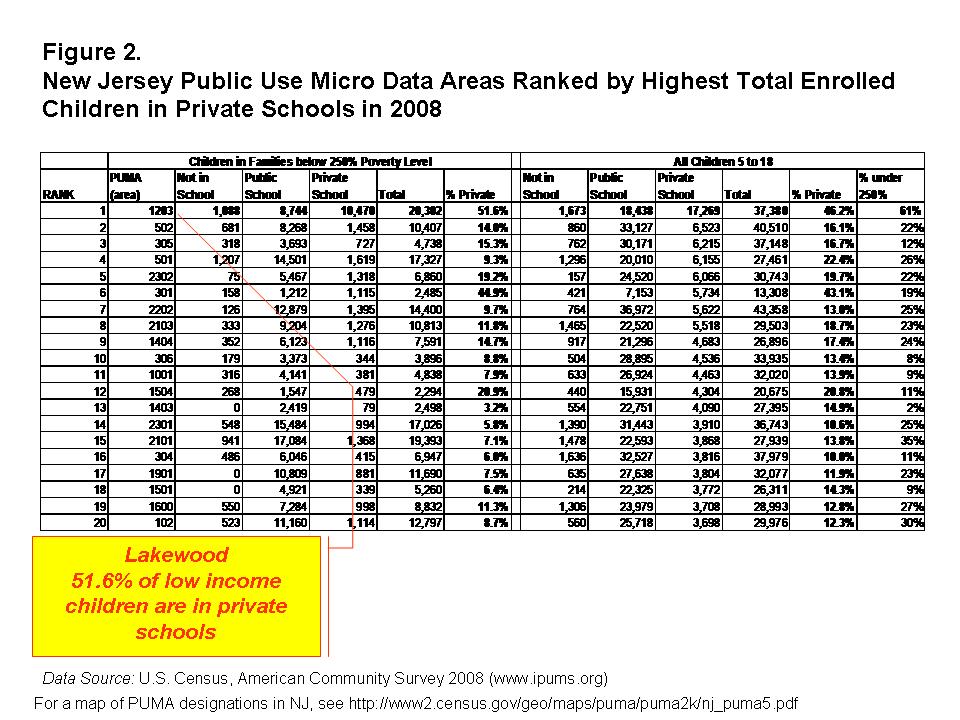

The next data we look at are from Public Use Micro-data Areas, or PUMAs – a construction of U.S. Census – which are smaller than metropolitan areas and allow for a relatively precise focus on the areas such as Lakewood. (PUMAs have populations of at least 100,000)

Because the Newark metropolitan area has far more than 100,000 residents, Newark would be carved into multiple PUMAs, whereas Lakewood would fall within one. But, the total populations of the areas would be more similar than comparing metro areas like those above.

Ranking PUMAs by private school enrollment, we find that the largest total private school enrollment – BY FAR – occurs in Lakewood’s PUMA, with about 17,000 children between 5 and 18 in private schools. About 8% of private schooled children statewide are in this PUMA. More striking however are the numbers of private schooled children who would qualify for the NJOSA vouchers. In Lakewood’s PUMA, that number exceeds 10,000 children. The next highest PUMA has under 1,500 who would qualify. Bottom line: Lakewood’s PUMA has over 20% of the state’s poor children who currently attend private schools.

The following tables present the data:

But this is only the beginning of the Lakewood story. As it turns out, the vast majority of children in Lakewood are in private, not public schools, which occurs nowhere else (to this extreme) in the state of New Jersey.

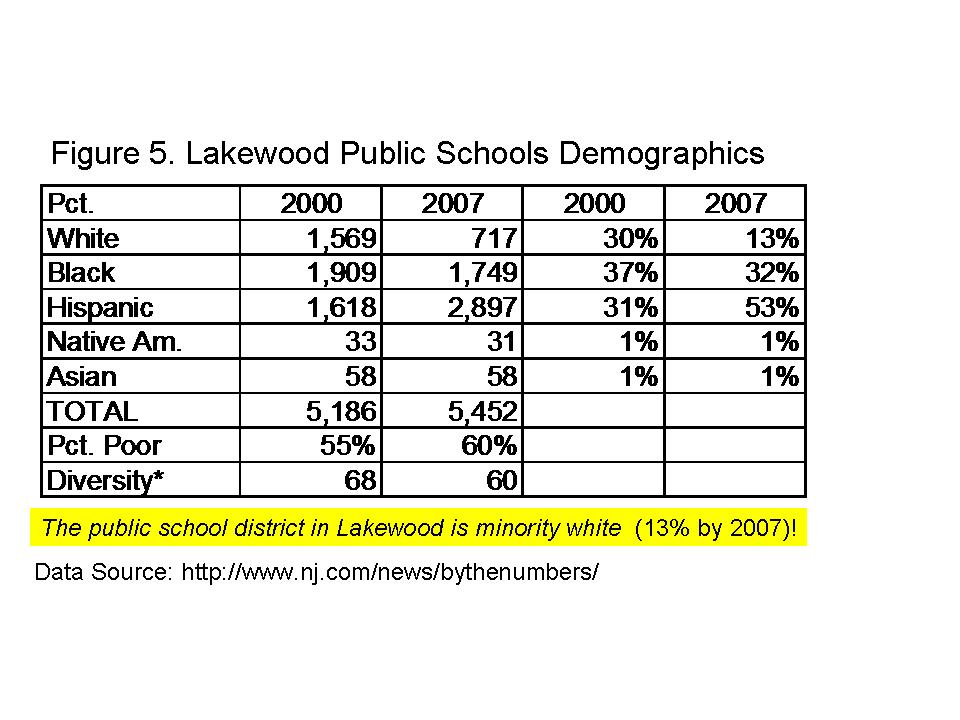

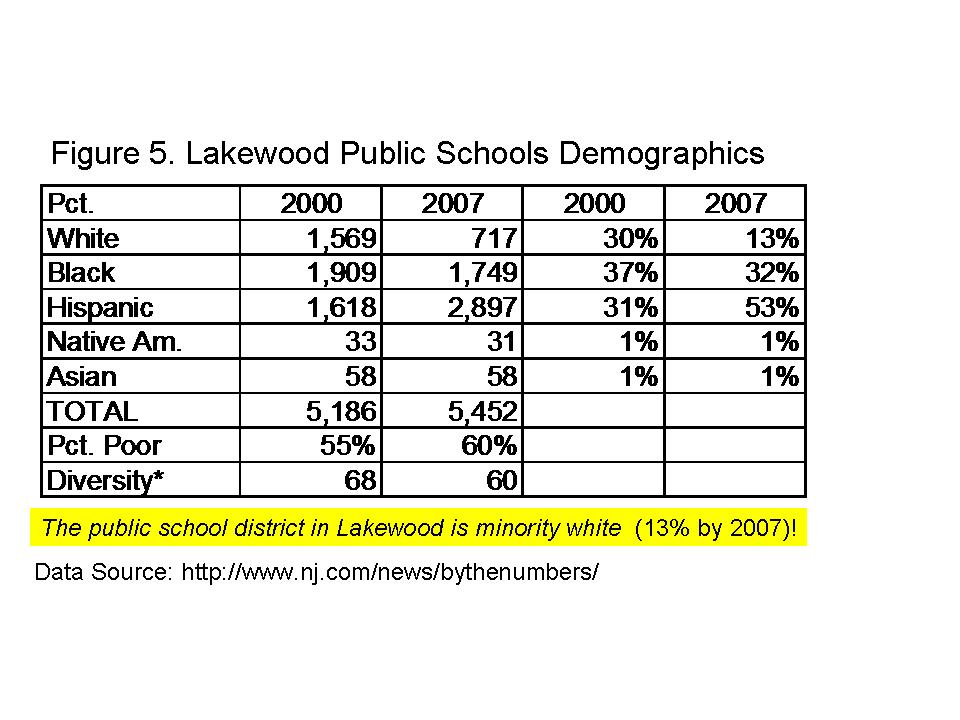

And, as it turns out, Lakewood’s public schools are currently “majority minority” (Black and Hispanic students:

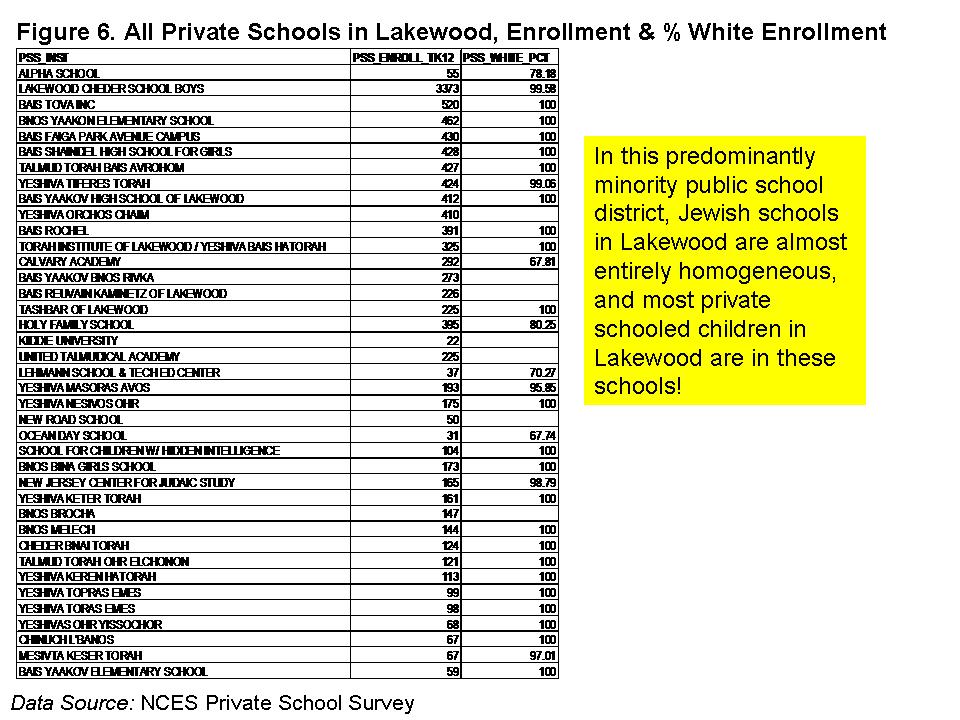

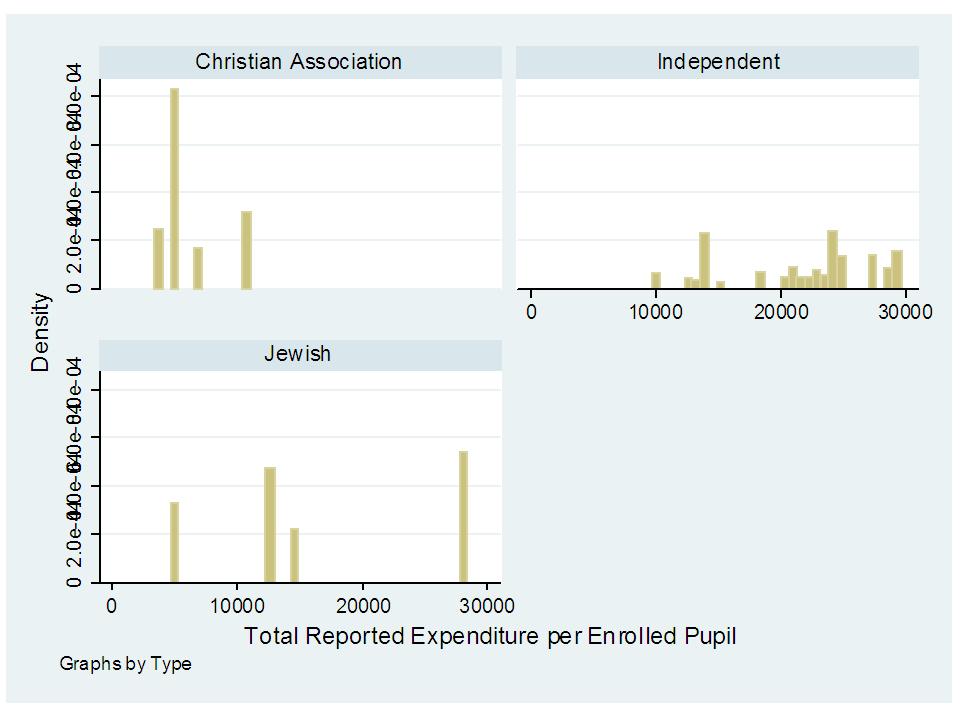

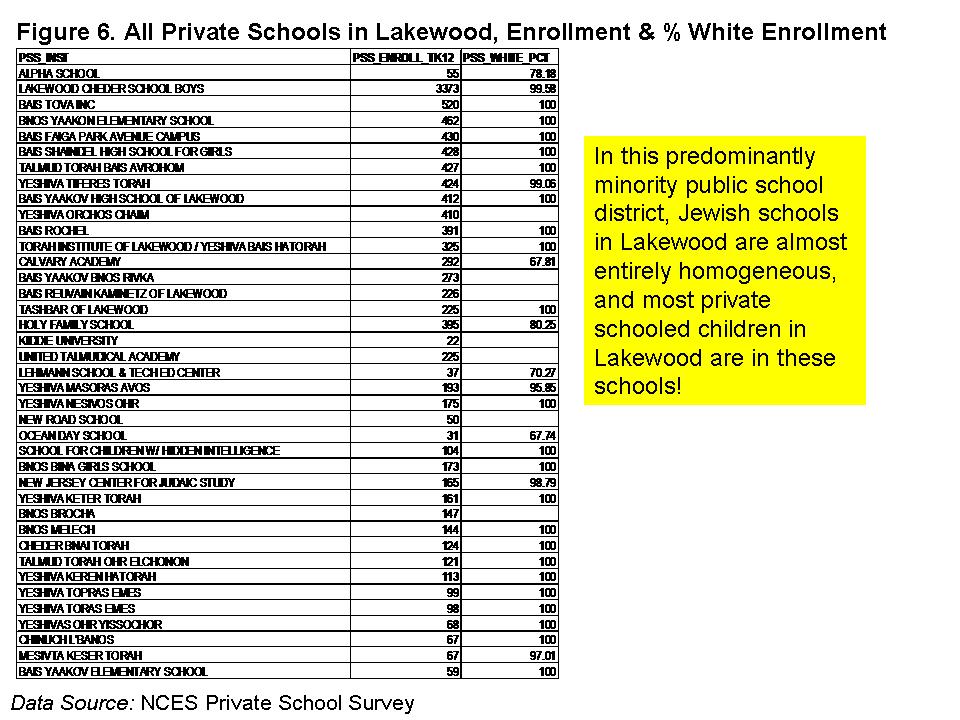

And, there are many, many private schools in Lakewood. The vast majority of those schools and the students who attend them are Orthodox Jewish schools which are almost invariably 100% homogenous – listed as “white” – in sharp contrast with the majority minority makeup of the township’s public school system.

As it turns out, the sum total of children attending the Jewish schools in Lakewood is approximately the same as the sum total of the low income (<250% poverty level) children attending private schools in Lakewood, or about 11,000. Needless to say, there is likely significant overlap between the children in Lakewood in private schools from low income families and the children in the Orthodox schools in Lakewood .

Note that 10,395 of the reported 10,470 (99.2%) poor, private schooled children in Lakewood PUMA were listed as “white” in the Census American Community Survey data from 2008. Only Lakewood’s Jewish schools match that demographic (in that geographic area). And they are nearly (if not entirely) all identified as low-income.

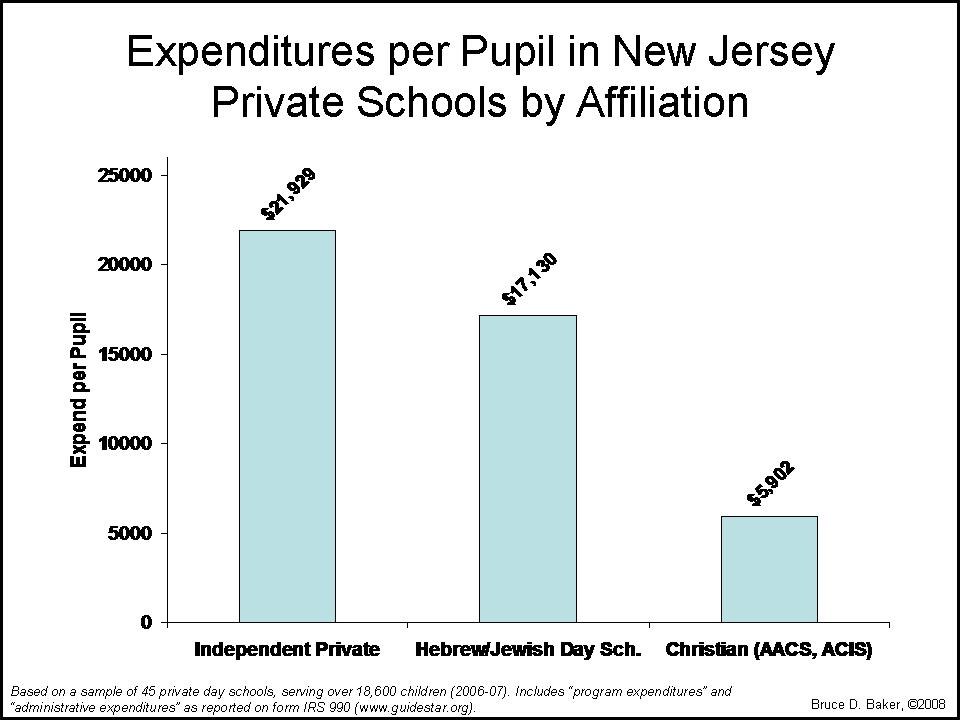

So who cares? Why does matter? What are the implications? Well, as it turns out this intriguing distribution of low-income private schooled children would potentially qualify Lakewood’s Orthodox Jewish schools for a sizeable revenue windfall from the NJOSA voucher program. It may not necessarily be enough to cover actual “costs” of operating these schools, but the publicly funded vouchers might go a long way to when combined with other resources.

Setting aside phase-in limits on the amount of total voucher funding under NJOSA, if all future children attending Lakewood Orthodox schools received vouchers each year, and if those schools maintained roughly the same enrollment as in 2008, the public revenue provided through vouchers could generate over $60 million per year for these schools.

Let’s sum up. One of if not the biggest beneficiary of NJOSA is not a) the children trapped in poor urban (Newark, Camden, Jersey City) schools, or b) cash-strapped urban Catholic Schools (which lack sufficient other private contribution support to keep afloat), but rather, the highly racially and religiously segregated Lakewood Orthodox Jewish community and its schools. They constitute the largest number – by far – of “income qualified” current private school enrolled children in the state

This is not quite the narrative about the NJOSA voucher proposal I’ve been hearing about.