I’ve been spending much of my spring and summer trying to get a handle on the various business practices of charter schooling, the roles of various constituents, their incentives and interests – financial and otherwise – in the operations of charter schools. Throughout this process, I also try to consider how or whether similar practices and incentives exist for traditional district schools and private schools and how these markets intersect. There will be much more forthcoming on this blog, and in academic papers and reports in the next few months and year.

But one issue really struck me as particularly ludicrous as I spent more and more time drawing pictures and mapping out business relationships. I had avoided for the longest time digging into the weeds of charter school land deals and facilities financing. It’s messy and there are certainly plenty of fun scandalous news reports on the topic. But when I see this kind of stuff, I ask myself – what policies enable – or perhaps even encourage these things? Where’s the boundary between legally permissible and not… and between good policy and bad?

Here, I provide an example of something that’s just bad public policy. I can’t really say… except in one piece of this puzzle (as I’ve laid it out), that there are any truly bad, unethical, or illegal actors in this scenario. But the outcome is still bad… bad… patently… amazingly stupid public policy.

It all started way back…such a long, long time back…Way back in the days when the grass was still green, and the pond was still wet, and the clouds were still clean, and the song of the Swomee-Swans rang out in space…

Oh wait… wrong story….

Let’s go to the diagrams…

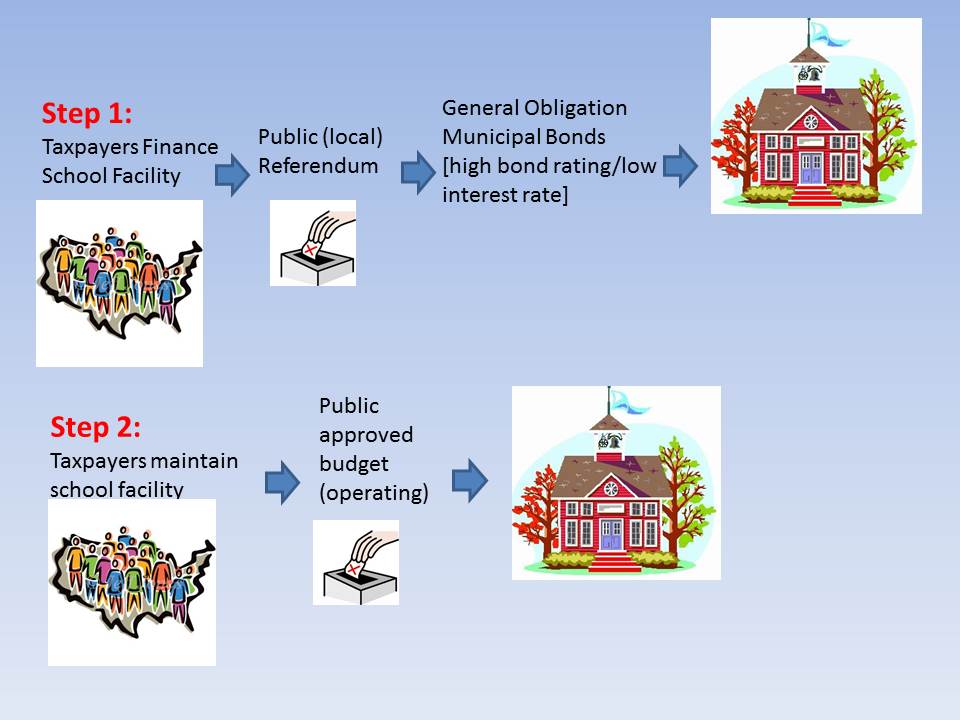

District controlled public school land and facilities are governed by the public that initially financed them. The public that financed these facilities and land acquisition typically did so by adopting in public referendum a promise to use their tax dollars (perhaps with support of state aid) to finance the debt required to buy the land and build the building. The public invested in the asset through debt financing, using low interest general obligation (GO) bonds.

Through annual budget approvals the public approved the maintenance of those facilities and their tax dollars were used to maintain their asset. The public invested in the maintenance of that asset through annual operating expenses of the district. Perhaps the public even approved additional debt financing along the way for improvements and renovations.

Many of these grand facades of public schooling were financed long enough in our past that we forget that they were financed with the tax dollars of previous generations and have been passed along and their care entrusted to the current generation.

Figure 1. The Initial Purchase & Maintenance

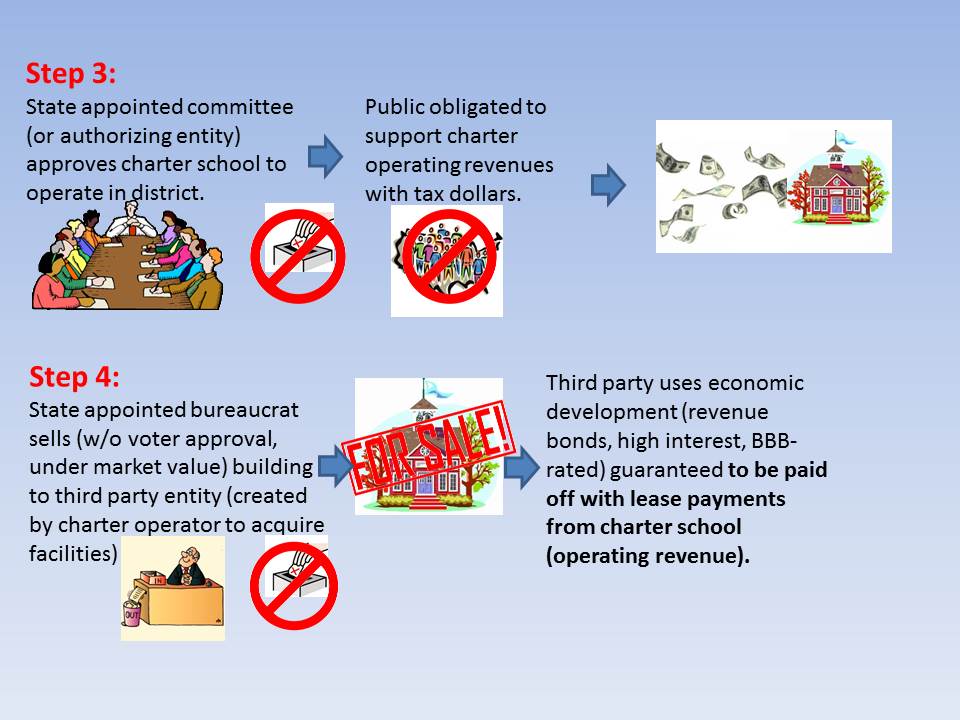

In many states, approval of charter schools to operate within district boundaries does not require local board or taxpayer approval. State government entities/appointees or elected bodies may serve as authorizers, and in some states, private entities and boards may authorize charter schools to establish, draw students and with them, public tax dollars for operating revenue/expense to support educational programs/services for those children.

Few states provide substantive support for charter school facilities acquisition and many/most states restrict charter schools (or district schools) from engaging in long term obligation of operating funds to finance debt, to acquire land and buildings. Instead, charter schools engage in lease agreements, typically shorter term, where lease payments are made from operating funds. But hey, who wants to be paying rent/lease year after year, and have nothing to show for it? State policies do typically permit, if not incentivize other organizations (including non-profit entities) to access “revenue bond” markets for urban re-development projects (in particular).

Quick primer on bond stuff:

General obligation bonds like those approved initially by voters for the facility are guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the municipality and taxes to be raised to pay off the debt. It’s pretty much guaranteed (except in the rare case that a town actually folds, entirely, financially, and say… picks up and re-establishes across the river). So, those bonds get pretty high ratings (from rating agencies) and thus low interest rates for paying off the debt.

Revenue bonds have to be guaranteed by the borrower with some revenue source. For third party entities purchasing land and buildings on behalf of charter schools, borrowers guarantee their bonds with the lease payments of the charter schools. Yeah… that’s right… the taxpayer subsidized operating funds for the charter school are used to make lease payments to a third party organization, which uses those lease payments to secure the debt to purchase the land/building. They usually get kind of a crappy interest rate (sometimes around 8.5% compared to, oh… about 4.5% for a similar size/structure GO bond) because the revenue source is less certain/more risky.

No clear, apparent harm/no foul here. Actually, it kind of makes sense for charter operators to collaborate to establish those third party land/facilities acquisition entities on their behalf, arguably a) so as not to get screwed with escalating lease payments down the line and b) to have an ownership stake in the property/asset. Now, some NJ charter operators caught some flack for creating different entities for each transaction and giving them strange names (like Pink Hula hoop), but I’m not sure I can blame them for the engaging in the increasingly common practice involved here.

Figure 2 shows the sell-off/property transfer process and this is where, when looking at the bigger picture, it starts to make less sense – from a public policy standpoint. Because charter school growth in cities often means declining district enrollments and facilities use, this potentially frees up under-used district facilities – perhaps even putting some on the auction block. In many cases, these facilities can be sold without local voter approval, even if voters had to approve their original financing. But that’s actually just a tangential concern here.

The really fun piece is that public tax dollars, channeled through the charter school are being used to purchase the facility, for the third party, from the public? Whah??? Whah??? Yeah… I’m buying it from me for someone else?

Huh…. ??

Figure 2. The Sell-off

To recap:

- Public buys facility with tax dollars

- Public uses tax dollars to maintain their asset

- Charter school uses public tax dollars (w/o public approval) to make lease payments to third party so they can buy same facility! (which public currently owns/controls)

- & pays crappy interest rate in process

- PUBLIC HAS BOUGHT SAME FACILITY TWICE (second time, from itself), AND NOW NO LONGER OWNS/CONTROLS IT!

That’s just dumb public policy even if, from the position of each of the parties involved, their actions would seem to make complete sense.

District – why should we keep maintaining a facility we don’t need? Can we generate some short term cash flow by selling it?

Charter operator – why should we make lease payments in perpetuity and have nothing to show for it? Why not collaborate to use existing policies to acquire assets?

Again, it’s not that anyone is doing anything ‘wrong’ (except that valuing these properties opens the door to manipulation), but rather, that public policy permits a bad deal for the public – one that essentially gives away a public asset while charging transaction fees along the way.

The major elements of the process differ little whether it occurs through loosely coupled, seemingly benevolent non-profits, or through for-profit charter management firms, their real estate acquisition arms and practice of flipping properties to real estate investment trusts (the major difference being the increased likelihood of rent gouging of the charter school in the latter version).

The absurdity of this relatively common example provides a case for seriously rethinking how we protect public interest and public assets as we move increasingly toward mixed delivery models of schooling – mixed in the sense that any jurisdiction might be served by a portfolio of traditional district schools, district governed or privately governed charter schools, etc.

I would argue that districts governed by public officials really need to be the stewards of these major public assets. This means that it may make more sense for state and local policymakers to craft more logical facilities management strategies which include co-location of charter schools (and the students they serve) – especially under state policies where charter schools are fiscally dependent (where charters receive funding as pass through from districts and where districts maintain responsibility for funding certain services for charter enrolled children). This means carefully evaluating and the appropriate and equitable operating subsidy rate for charter schools, given the children they serve with consideration for the facilities provided.

A secondary reason why maintaining public control over these assets is critically important is that it provides district officials (and the public they serve) the flexibility to change course – to decide, if/when that time comes, that it’s time to reign in charter/choice programs and reclaim a major role for traditional public schooling. Once the public assets are sold off under the model above, they are gone, and costs of rebuilding may be prohibitive. That’s a dangerous path for the future of our cities and children and families that inhabit them.

Yes – I am making a case for rethinking co-location as an option, or more broadly – centralized capital asset management. Co-location is contentious and there are a lot of tricky, politically and technically messy details to work out.

But, it’s a lot better than this alternative!

This needs to stop now!

========================

Addendum:

Fun debates on the sidelines about this topic. For example, how are my examples above any different from any individual person paid with public funding (public employee) buying any previously public asset? Aren’t these examples merely about a private contractor purchasing an asset, any asset, with the proceeds of their appropriately compensated work?

Now, it is conceivable that a charter school and its employees could take an approach that is seemingly more appropriate for private asset acquisition, even using what was originally the public dime (now, I’ve not said there’s anything wrong with what the charter is doing above, except that bad public policy allows it to happen). A charter school could, instead of making the lease payment as a mere pass-through of public subsidy, simply pay all of its employees higher wages to the sum of that payment and then permit them to individually contribute to a fund either for the direct purchase of the property or indirect purchase via lease payment to the third party. But that would involve individual decisions regarding the use of their compensation. It’s not an institutional decision to simply pass the money through, and it’s seemingly less problematic unless the institution FORCES their employees to contribute that portion of their wages for purchase of the property.

I’ll talk about ways in which charter operators forcibly tax employee wages (for self gain) in a future post!

Now, one other public policy protection here might be to declare any assets acquired by the private contractor with public dollars to be owned by the public. This dispute has occurred elsewhere, as far back as when Education Alternatives, Inc. (1996) gained a management contract with Hartford CT schools and used start up funds to acquire technology.But given that many charter operators reasonably mix expenditure of public and private dollars, parsing who owns what can be exceedingly complex.

Of course, it may be reasonable to expect those charter operators who wish to privately own a facility to finance that facility with appropriately segregated private revenue sources.

Would it make more sense then for the district to sell the asset to some other private entity, like a real estate developer? and let the charter operators fend for themselves to find suitable educational spaces? That would seem a raw deal for both. The public loses the public asset, likely never achieving appropriate compensation for that asset, and the charter likely faces greater costs (extraction from their operating revenue) than could be achieved by thoughtful centralized facilities management.

One final note: A central issue above is that there is value to controlling these public assets which justifies the costs of maintaining them over time. Private entities have no interest in making sure that sufficient assets remain available for the provision of public schooling (regardless of provider type), just as private landlords have no interest in ensuring sufficient availability of affordable housing. For cities to be able to provide sufficient educational services to all those in need, now and long into the future, cities need a plan for maintaining sufficient capital stock. Similarly, if we value public parks and libraries, we can’t expect private markets to provide them in ways that will make them broadly, publicly available. We must subsidize them publicly, and maintain them publicly (even if we pay private contractors to do that maintenance).

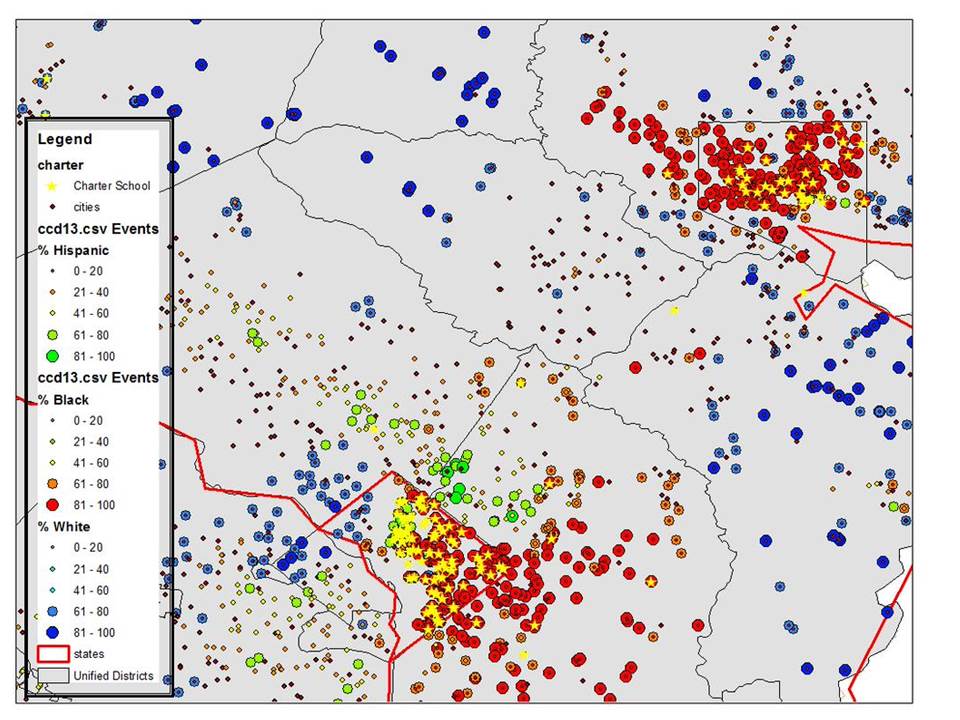

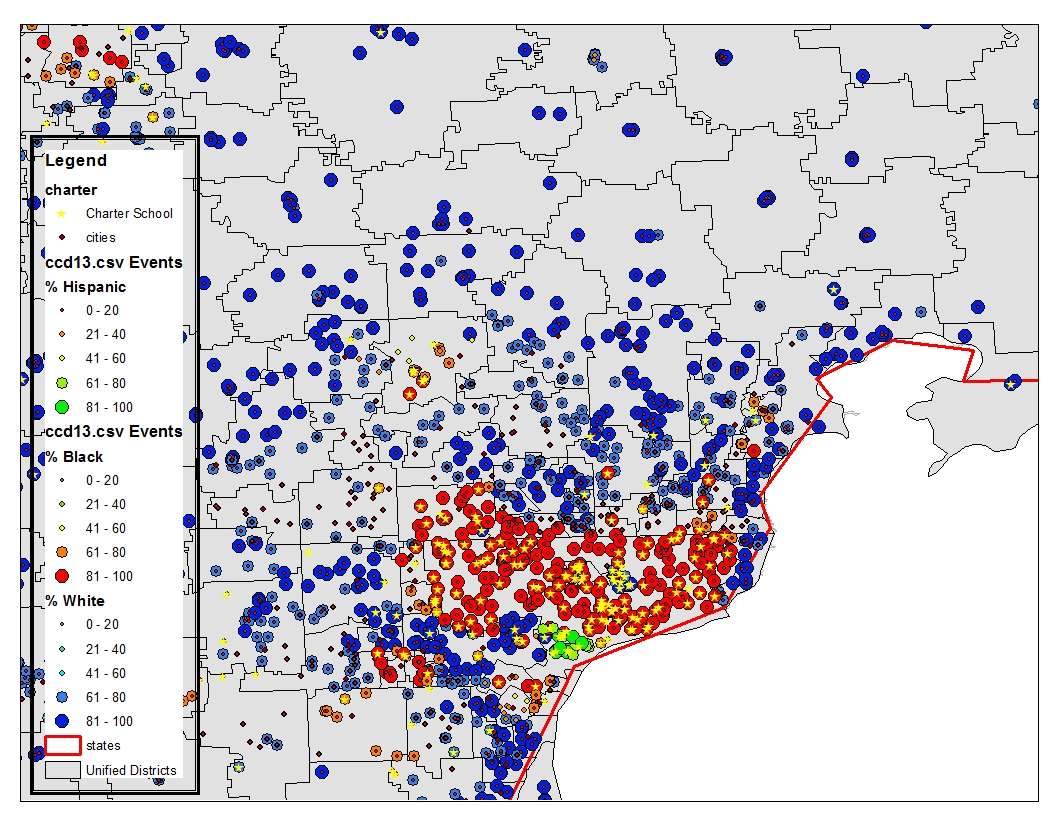

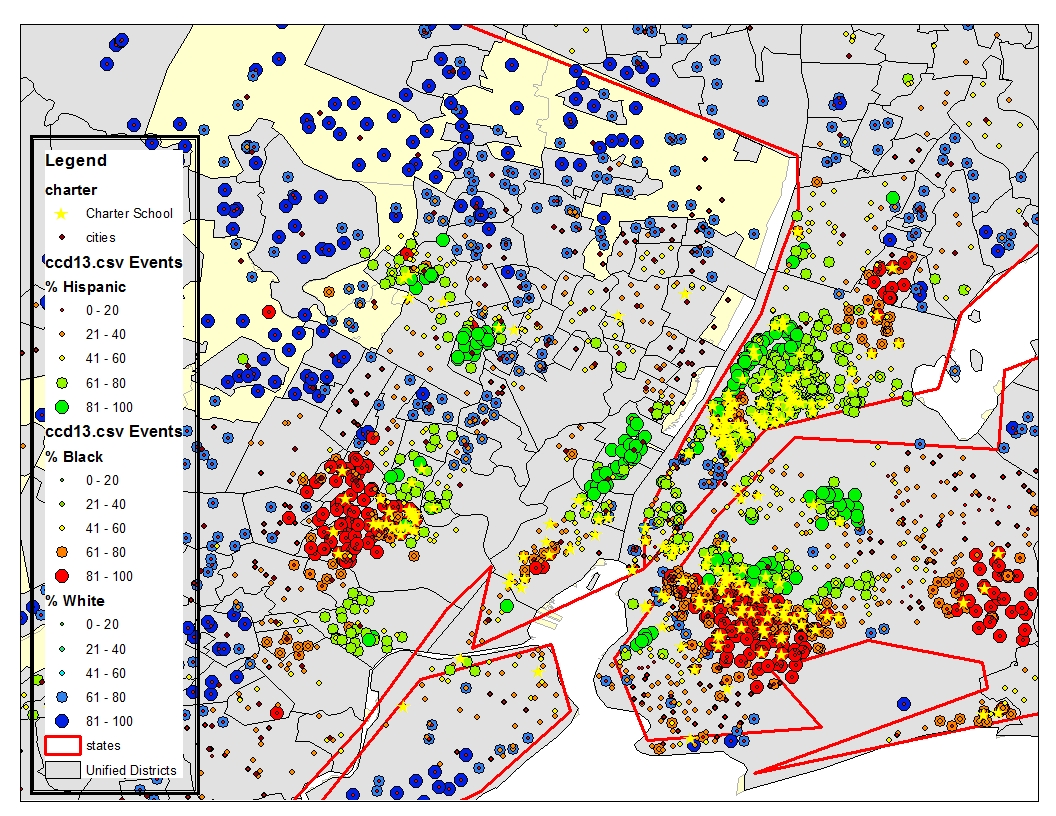

Note: The figure below, constructed with data from the NCES Common Core, Public School Universe Survey shows that while in some major cities there has been overall decline in students in district and charter schools (cumulative), the transfer of students between district and charter schools tends to explain more of the district school enrollment decline. As such, the demand for facilities space is not declining substantially, but rather, shifting. Hence the interest in maintaining and managing a more constant capital stock to meet the needs of these children.