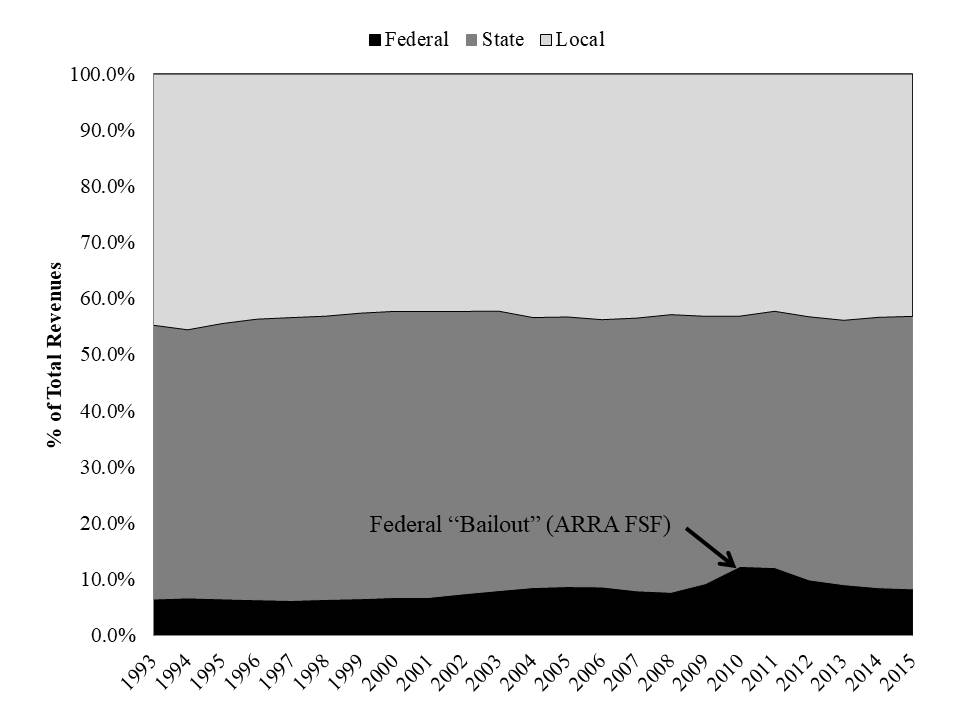

Among the take-home points of our recent review of Newark school reforms are that:

- Resources, when considering school size, are positively associated with growth;

- The productivity of large charter operators in Newark – TEAM and North Star in particular – depends on how we treat school size in our models;

- Jumps in student growth percentiles across the board between 2014 and 2015 are hard to explain as a function of substantive policy change – where policy and contextual changes had been happening gradually prior to and throughout the period.

From any study of the effects of changes in policy and practices on student outcomes, what we really want to know – where positive outcome effects are observed – is what can be done to distribute those positive effects across more children and settings, and/or yield even stronger positive effects.

The conclusion offered in the reports is that shifting students to higher value-added schools has yielded positive growth in language arts. And thus, the logical policy conclusion is that more students should be shifted to high value-added schools. The larger the share of students placed in these schools, the higher the overall system performance will be. This may be an oversimplification, but is certainly the message that some are taking home from the reports.[i]

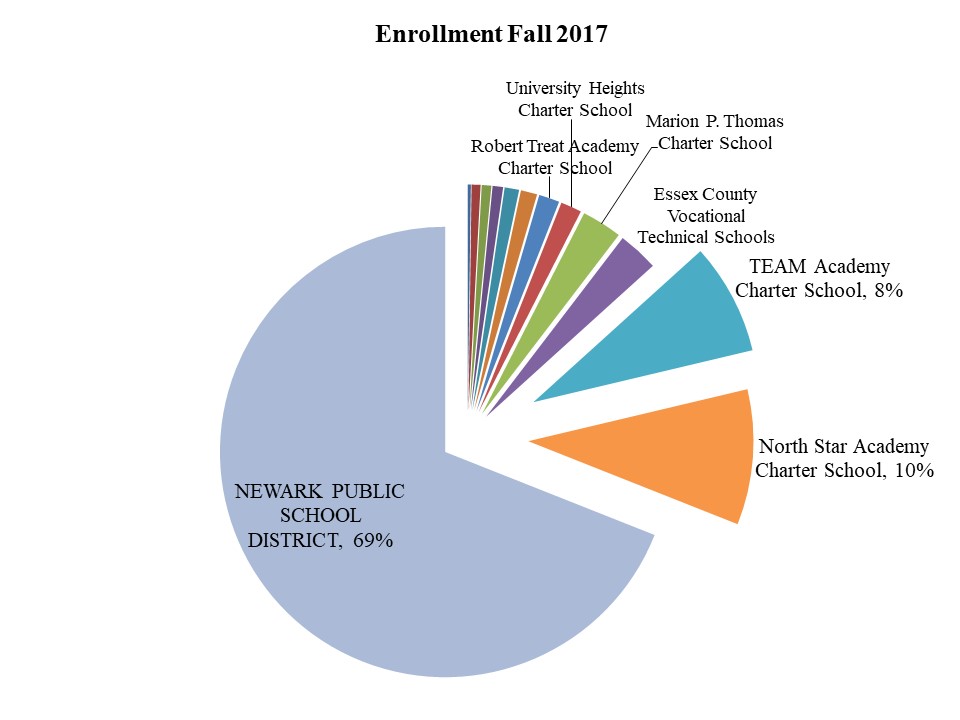

Figure C1 shows the present distribution of students across district and charter schools within the city of Newark. One might characterize the system as housing 3 separate K-12 school districts with a handful of smaller operators of select grade-level schools. The three comprehensive districts in question are NPS, TEAM and North Star. Analyses in the previous section (setting aside the scale question) suggest that TEAM and NPS perform similarly and that North Star tends to be the higher producer of student growth. Thus, the assertion would be that if we shift more students into North Star, more students should be better off and the system as a whole should produce better outcomes on average.

Thus the “between-school” treatment here is essentially defined as “North Starring” more students. But what exactly does that mean? Here, we attempt to provide some relevant context. Our intent is to separate the treatment of “North Starring” into those actions district leaders and policymakers might take which are desirable and scalable, versus those practices and conditions that are likely to be influencing measured outcomes but may not be scalable or desirable.

Figure C1

Distribution of District and Charter School Enrollments in Newark 2017

Source: New Jersey Department of Education, Enrollment files, 2016-17.

http://www.state.nj.us/education/data/enr/enr17/

Student Population Differences

Unfortunately, a consistent feature of North Star Academy over time has been the tendency to serve and retain less needy student populations than the broader population in the district as well as other charter operators including TEAM. Neither TEAM nor North Star serve many children with severe disabilities, but North Star serves very few with disabilities of any degree of severity. The reports’ analysis fails to parse severity of disability – its influence on individual student growth, the potential peer effects of the presence of children with severe disabilities, or the extent to which larger shares of children with severe disabilities create resource allocation constraints and pressures in schools. This is a substantial omission, but one which could not be remedied given the lack of data precision.

North Star has also consistently served proportionally fewer of the lowest income children. Again, the reports’ analysis fails to parse income levels across children, using only indicators of children qualified for either free or reduced priced lunch. We provide illustrations in this section demonstrating why this matters.

North Star serves effectively no children with limited English language proficiency, in part because North Star caters to a predominantly black student population from Newark’s black neighborhoods, which remain geographically segregated from the city’s Hispanic and other ethnic neighborhoods and are home to non-English speaking families.

Special education rates

We start with disability rates based on 2016 data, which are actually more similar across the three Newark districts than prior years during the period studied. Figure C2 shows the overall percent classified and percent with mild specific learning disability, other health impairment, or speech/language disability. Newark Public Schools has an overall rate higher than either of the other two and more than double that of North Star. The vast majority of children with disabilities in North Star have relatively mild and less-costly disabilities. The case is similar for TEAM. Notably, TEAM and NPS have similar rates of mild disability students, but NPS has far more severe disability students.

This finding actually serves to rebut a common argument of charter advocates regarding their lower disability classification rates. Charter advocates frequently assert that effective early grades interventions reduce their need to classify students with disabilities.[ii] But even the most effective interventions would only be successful at reducing the number of children identified as having mild specific learning disabilities – children on the margins of classification. Interventions would be far less likely to reduce classification of children with traumatic brain injury, intellectual disability, emotional disturbance, or autism. It is those more severe and costly disabilities which are more prevalent in the NPS schools. Whether valid in other settings or not, this argument is unlikely to hold for differences in special education classification rates between NPS and TEAM Academy.

Figure C2

NJDOE Special Education Classification Rates: http://www.nj.gov/education/specialed/data/2016/LEA_Classificatiom.xlsx

Figure C3 provides a more detailed breakdown, revealing that a very large share of North Star’s disability population are children with Speech/Language impairment, and no particular cognitive, behavioral, or other severe impairment which would either divert more substantial shares of resources or directly influence student achievement growth.

Most analyses of Newark district and charter school performance, matching on or controlling for disability status in the aggregate, presume that these children in North Star are equivalent to children with far more severe disabilities in NPS. Some studies specifically find that children with disabilities in charter schools show greater gains than children with disabilities in district schools.[iii] In this case (and most other contexts we’ve studied), such a finding – applying a single measure of “disability” – would be spurious, in that obviously children with only speech language impairment on average would achieve greater growth on standardized assessments than children with multiple and severe learning disabilities.

Figure C3

NJDOE Special Education Classification Rates: http://www.nj.gov/education/specialed/data/2016/LEA_Classificatiom.xlsx

To summarize, these disability population differences alone, which go unmeasured when using a single “has disability” dummy variable, affect:

- relative growth between charter and district school students,

- the nature of peer groups (proportions of marginal vs. more severe disability students integrated into regular classrooms could affect the pace of the curriculum and disruptions in classroom time, which likely would affect growth),

- the extent to which higher need student populations create resource pressures and drive reallocation away from “general education” students.

While on the one hand these population differences raise questions regarding assumptions about the effectiveness of North Star Academy, they also raise questions about the scalability of “North Starring” and its effects on the system as a whole, even if North Star is particularly effective with the students that it does serve and retain. The more non-disabled students a single large district in the city enrolls, the more disabled students the other districts will have to serve.

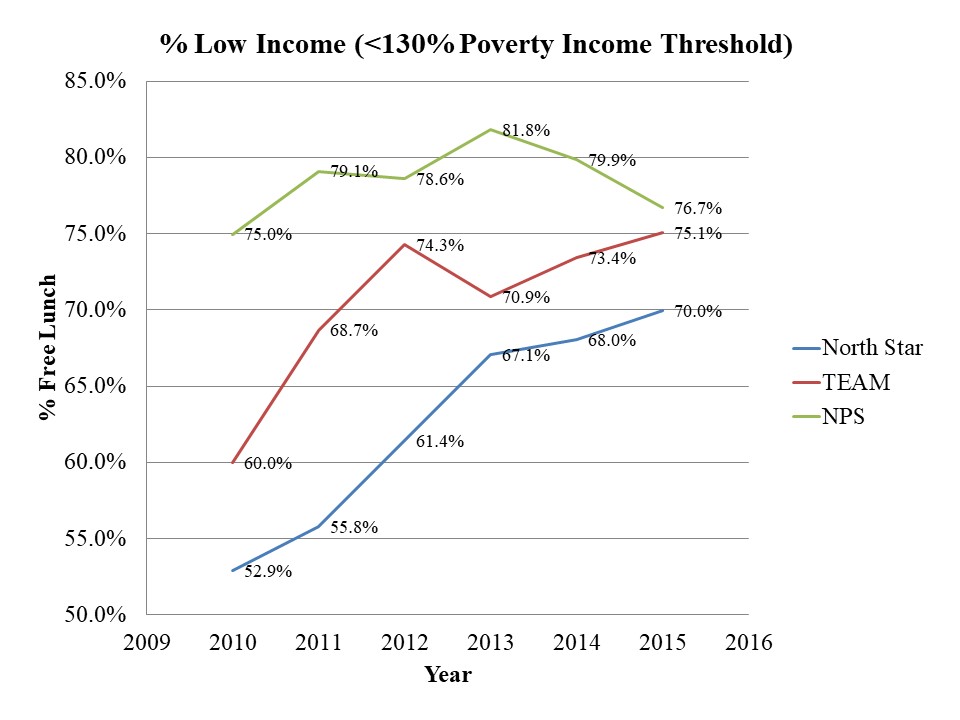

Low income concentrations

During the “reform” period under study, substantive differences in the shares of children qualified for “free” lunch existed. These gaps have been closing in recent years; however, North Star continues to serve a smaller share of children who fall below the 130% income threshold for poverty than either TEAM or NPS.

Figure C4

The Chin et al. study compares students only on the basis of “free + reduced” priced lunch. Single dummy variables on free and reduced-price lunch are relatively meaningless in a context where nearly all children fall below the higher threshold (less than 185 percent of the income poverty level). In fact, those qualified for reduced price lunch are among the more relatively “advantaged” students in the district and schools with higher shares of those students tend to have higher average scale scores.

Table C1 shows the correlations between percent free lunch, percent reduced-price lunch, percent free and reduced-price lunch, and growth and scale score outcome measures across Newark Schools, including district and charter schools. To summarize:

- Percent free lunch has a small negative correlation with growth percentiles and a large negative correlation with scale scores.

- Percent reduced lunch is positively correlated with growth and strongly positively correlated with scale scores.

- Percent free and reduced-priced lunch is only modestly negatively correlated with scale scores.

This is because those students from families between the 130% and 185% income threshold for poverty happen to be the more “advantaged” students in this high-poverty, urban setting. That is, at the school level, percent free and reduced-priced lunch tells us little about the “risk” of low performance largely because nearly all children in Newark fall below the 185% income threshold for poverty. In addition, it is likely that a substantial number of those who are not identified as qualifying for either in fact do qualify, yet are not listed as such because their families did not apply.

By extension, using a single dummy indicator as a covariate in student (or school) level analysis that assumes nearly all Newark students are socioeconomically identical to one another will lead to specious findings. Because shares of lower income children vary systematically by sector – between NPS and charters – those conclusions will be biased in favor of charters generally, and North Star specifically. While North Star has shown impressive unconditional growth, it has continued to serve fewer of the poorest children in the city. TEAM also served fewer of the poorest children throughout the period studied.

Table C1

Correlations between Growth, Achievement Level and Low Income Populations in Newark (2016)

| LAL SGP | Math SGP | PARCC Math 8 | PARCC ELA 8 | % Free | % Reduced | |

| LAL SGP | 1 | |||||

| Math SGP | 0.5807* | 1 | ||||

| PARCC Math 8 | 0.3758* | 0.4686* | 1 | |||

| PARCC ELA 8 | 0.4836* | 0.4465* | 0.9043* | 1 | ||

| % Free | -0.0984 | -0.0734 | -0.3890* | -0.5052* | 1 | |

| % Reduced | 0.3440* | 0.3817* | 0.6602* | 0.8062* | -0.1233 | 1 |

| % Free or Reduced | 0.0444 | 0.0779 | -0.1638 | -0.223 | 0.9348* | 0.2373 |

In addition to compromising validity of high versus low value-added findings, the tendency of between-school mobility to sort students by income status raises scalability concerns. Put bluntly: as one school/district in a high poverty “choice” space serves more of the less-poor (among the poor) students, others must pick up the difference. Concentrating higher-poverty populations in specific schools potentially creates negative peer effects that are not picked up when using test score histories as measures of peer characteristics.

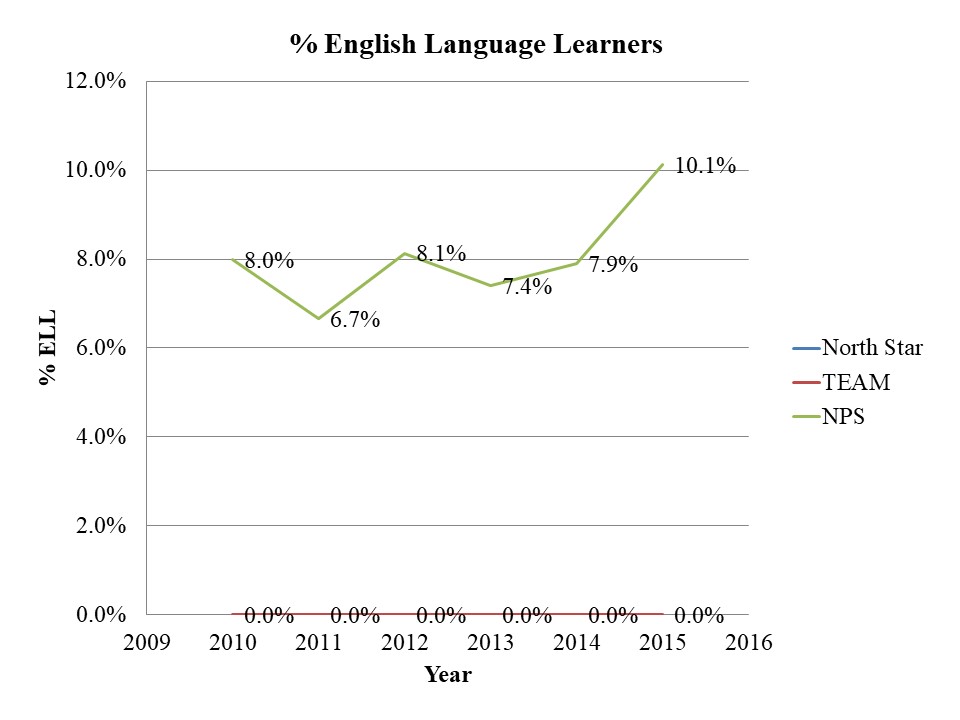

English Language Learners

Figure C5 shows that among the three districts in Newark, only NPS serves any children with limited English language proficiency. As about 10% of the NPS population is LEP/ELL, this, again, raises questions about scalability. The more that charters in the space serve non-LEP/ELL children, the more LEP/ELL children are concentrated in the district schools. As with poverty and disability, it is also desirable to have access to more fine-grained data on the level of language proficiency.

Figure C5

There remain large differences in shares of English Language Learners Served

New Jersey Department of Education School Enrollment Files: http://www.nj.gov/education/data/enr/

Cohort Attrition Rates

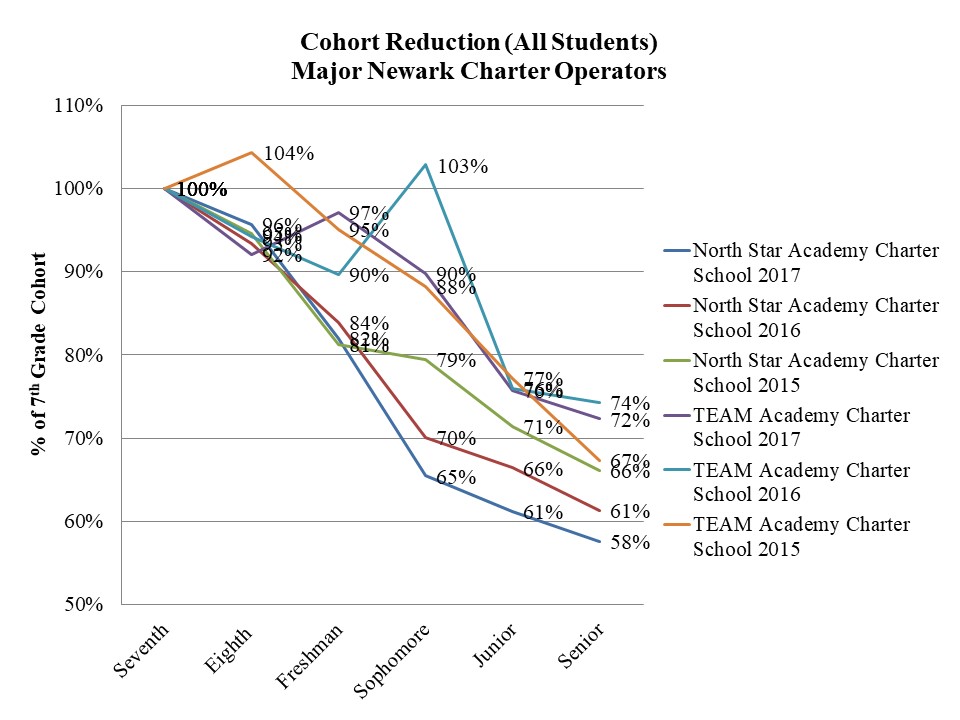

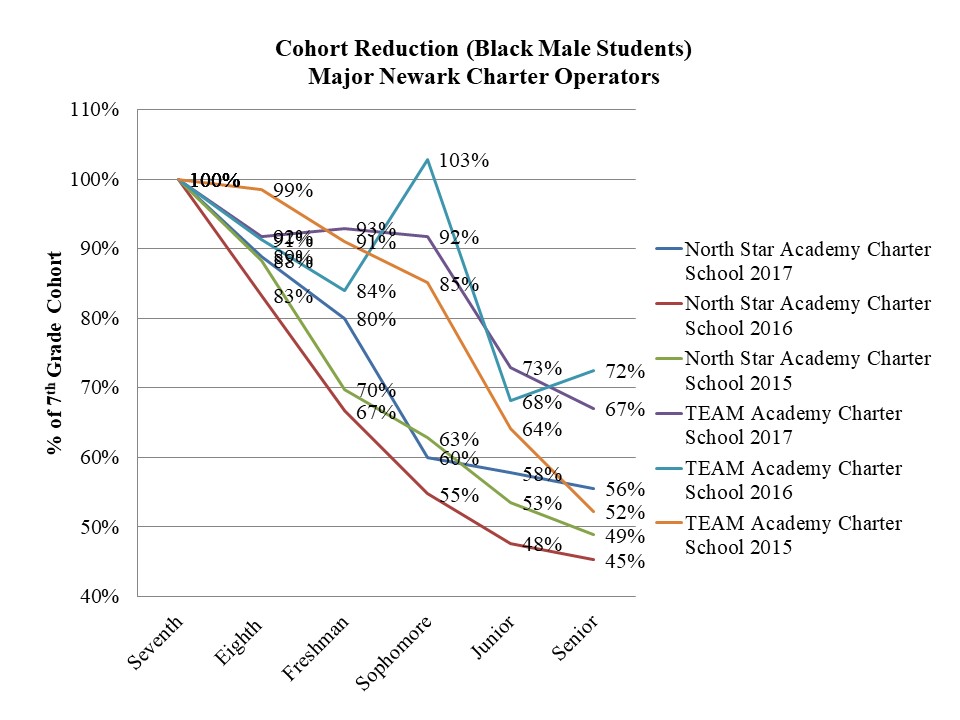

Figure C6 and Figure C7 track cohort attrition rates for three sequential cohorts attending TEAM and North Star. Figure C6 shows the total cohort enrollments and Figure C7 shows the cohort enrollments for black male students. Figure C8 shows the average ratio of the 12th grade enrollment to the 7th grade enrollment of the same cohort of students.

Figure C6

Seventh Grade Cohorts, year after year, are reduced by 25 to 40% as they matriculate to 12th grade

Figure C7

Seventh Grade Cohorts of Black Boys, year after year, are reduced by 28 to 65% as they matriculate to 12th grade

New Jersey Department of Education School Enrollment Files: http://www.nj.gov/education/data/enr/

Figure C8

Cohort progression rates are much higher for Newark Public Schools than for TEAM and North Star

New Jersey Department of Education School Enrollment Files: http://www.nj.gov/education/data/enr/

Certainly much can go on between 7th and 12th grade which affects these cohort enrollments. Students can be held back, boosting the prior grade in the subsequent cohort. Cohort reduction might be mitigated by what is called “back-filling” – admitting new students to fill the spaces of students who leave. Also, after 8th grade, some students may choose to leave for other schools, including selective magnet or private schools.

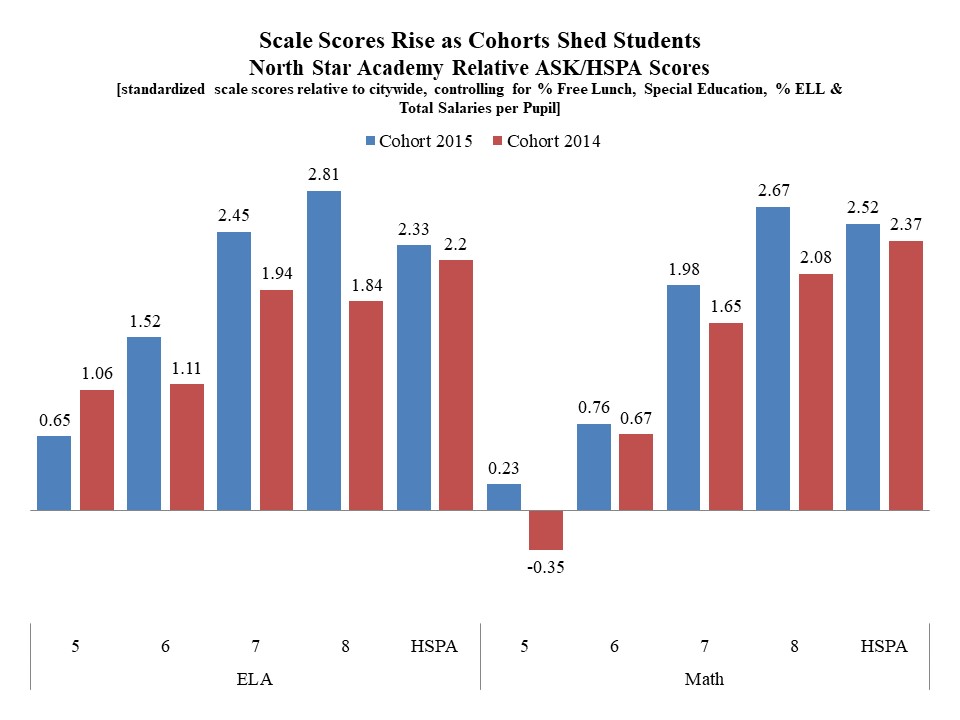

However, if a cohort by 12th grade is substantively smaller than it was in 7th grade, the most likely explanation is that students have left. This cohort attrition might include those who were pushed out and/or counseled out due to behavior or low academic performance, as well as those leaving for private and magnet schools. If the former is true (weaker and “problem” students leaving), we would expect cohort test scores to go up. If, however, the latter is true (students qualified for selective schools leaving), we might expect cohort test scores to go down. Figure C9 addresses this issue.

These figures show that both North Star and TEAM have significant cohort reduction between 7th and 12th grade for all students and even more so for black boys. Senior cohorts of black boys in North Star are half or fewer than the 7th grade cohort.

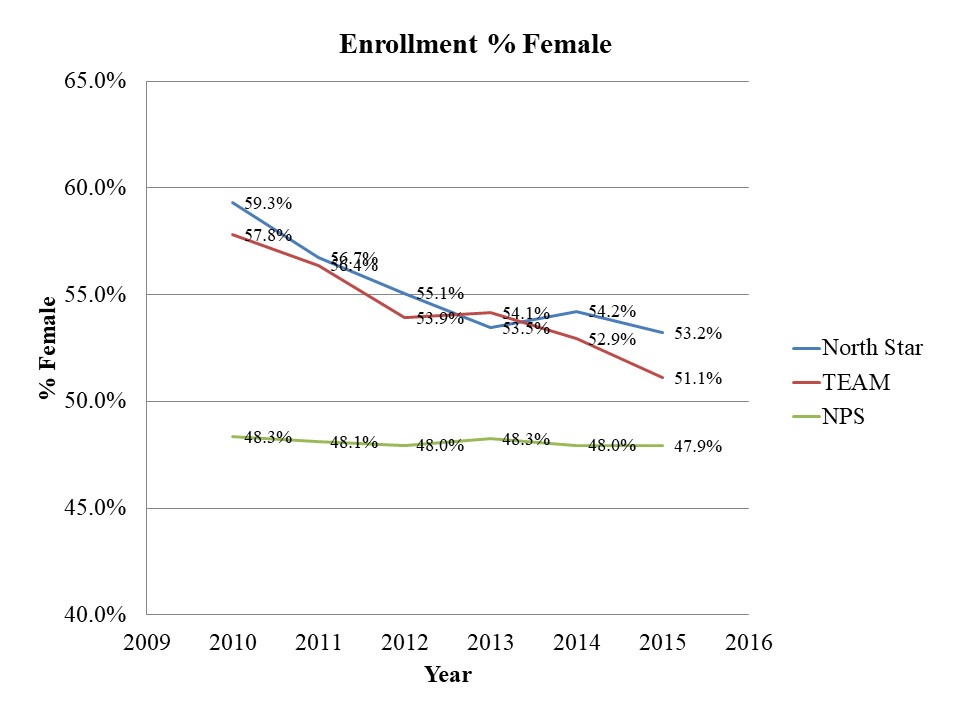

Figure C10 shows that, perhaps in part due to the attrition of black boys over time, these schools also tend to be majority female. As a result, Newark district schools are majority male.

Figure C9

Scale Scores of Cohorts through Progression/Attrition

New Jersey Department of Education School Enrollment Files: http://www.nj.gov/education/data/enr/

Statewide Assessment Reports: http://www.state.nj.us/education/schools/achievement/index.html

Figure C10

Large charter schools continue to serve predominantly female populations, perhaps as a result of shedding black male students

New Jersey Department of Education School Enrollment Files: http://www.nj.gov/education/data/enr/

Finally, along with very high attrition rates for black boys, North Star and TEAM Academy continue to have very high student suspension rates. As Figure C11 shows, North Star suspends 30 percent of students year after year.

Figure C11

North Star and TEAM Academy continue to have among the highest suspension rates in the city of Newark (sorted by 2015 rate)

New Jersey Department of Education School Report Cards/ School Climate: https://rc.doe.state.nj.us/ReportsDatabase.aspx

As a matter of policy preferences for moving forward, these findings raise concerns. Again, the most prominent conclusion from the reports is that citywide gains are achieved by moving more children into high value-added schools, where the largest of those schools – a district within the district – is North Star. North Star’s value-added, however, is achieved at least in part (if not in majority) by:

- not serving children with disabilities generally and serving no children with severe disabilities;

- serving very few lower-income children,

- serving no ELL children;

- having very high attrition generally, and 50% or greater attrition of black boys between 7th and 12th grade; and

- suspending large shares of children year after year.

Having studied these schools year-after-year for nearly a decade, we are confident that these factors taken together are a “feature” and not a bug when it comes to North Star, and remain a feature, though to a lesser extent, in TEAM Academy. These factors are not captured in the reports’ analysis. Yet they a) limit the validity of assertions that North Star in particular could be a high value-added school for the general population and b) raise serious concerns regarding policies that would attempt to shift more students to North Star, or schools like it, without first addressing these issues.

Paying teachers more to work more hours and days

Here, we address other features of North Star and TEAM as they relate to the host district. These “resource” features may provide more relevant policy insights to the extent that they contribute, in part, to student achievement gains. Resources are legitimately manipulable and scalable features of school systems – at least more so than student sorting by disability and poverty, and selective attrition. Isolating the extent to which these resource factors relate to achievement gains, however, is difficult in the context of these other factors.

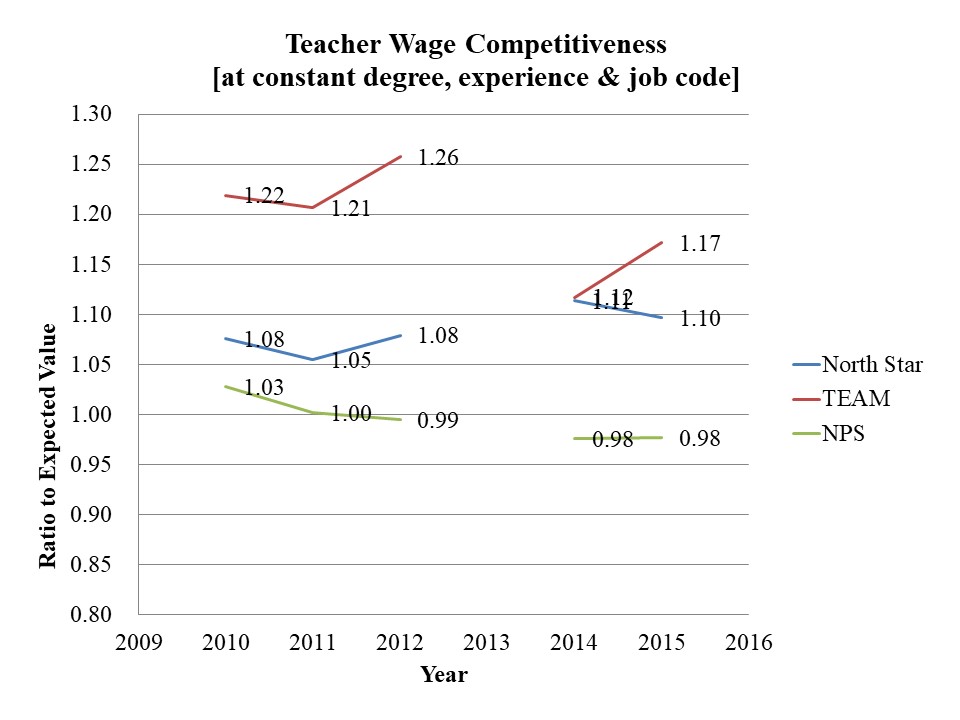

Among other things, North Star and TEAM Academy operate longer days (over 8 hours, compared to 6 to 7 for NPS schools, according to state report cards) and longer school years. Figure C12 shows that, on average, teachers in these schools are paid higher wages at similar experience and degree level for this additional time commitment. Teachers in TEAM Academy are paid as much as 20 percent more for their time, compared to teachers with similar characteristics in similar job positions throughout Essex County. Teachers in North Star Academy are paid about 10 percent more. Meanwhile, the relative competitiveness of teacher wages for NPS teachers has slipped below the wage for comparable teachers countywide.

The relevant policy question is: to what extent is this specific investment in teacher wages, for additional time, contributing to the higher value-added at North Star? These differences – time and money – are clearly part of the “treatment” which results from shifting kids from district schools to these two charter operators in particular. Yet this feature of differential treatment between district and charter schools was not addressed in the reports.

Figure C12

Higher pay for longer days and more days

NJDOE Staffing files, 2009-2016.

Relying Heavily on Novice Teachers

Given the relatively higher wages at TEAM and North Star and the schools’ commitment to providing longer days and years, one must question how these schools can keep their ongoing total labor costs under control and sustainable over time. That is, can labor costs be managed in the long run, at even larger scale, while providing 10 to 20 percent compensation increases to support additional contractual time commitments?

Figure C13 provides one answer to how TEAM and North Star have kept their total labor costs in check. These schools maintain staffs with very high shares – up to half – of teachers having three or fewer years of experience. At those experience levels, they are paid more than they would be in the district or elsewhere around the county; however, their average salaries are lower because of their inexperience. TEAM’s teaching staff is substantially less novice than is North Star’s teaching staff.

One explanation for the large shares of novice teachers in these schools is that they have expanded year after year and have needed new teachers. However, the question remains whether these schools can maintain their approach of longer days and years for higher pay if these teachers stick around and become more expensive over time. If the model depends on continued turnover to keep spending under control, it may not remain sustainable, especially as it is brought to scale.

Figure C13

Heavy Reliance on Novice Teachers

NJDOE: Staffing files, 2009-2016.

Out-Of-District Peers

According to state records, a substantial portion of Newark’s charter school students are not residents of the district. In New Jersey, charter school funding comes from the district where charter students reside. We use the state’s charter aid notices[iv] to those districts to calculate the percentages of students who reside outside of the district. In total, 8 percent of Newark’s charter school students are not residents of the city.

Figure C14 shows the percentages of non-resident students by individual charter school. Over half of the student population at two of Newark’s charters do not reside in the city. Notably, 8 percent of TEAM/KIPP’s students are not Newark residents, while North Star has the highest proportional enrollment of students living in Newark.

It is likely that students who have the ability to travel to another district have unobserved differences in their personal characteristics compared to students who cannot travel. This creates a potential bias in estimates that are derived from comparing non-resident charter students to resident NPS students.

Figure C14

NJDOE, FY17 Charter School State Aid Notices.

Staff Certifications and Curricular Narrowing

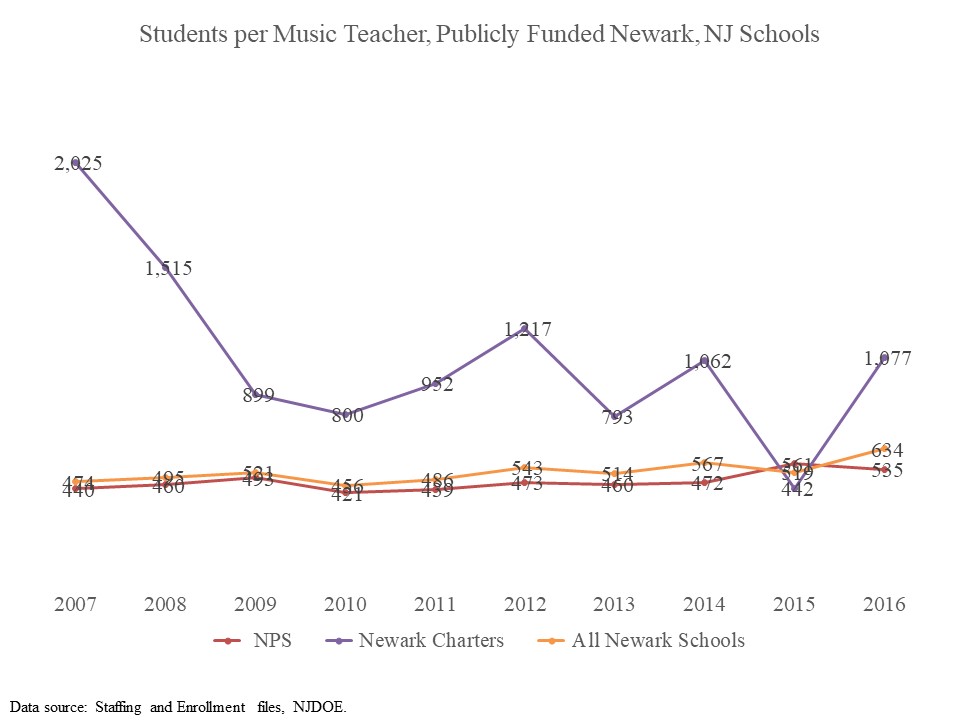

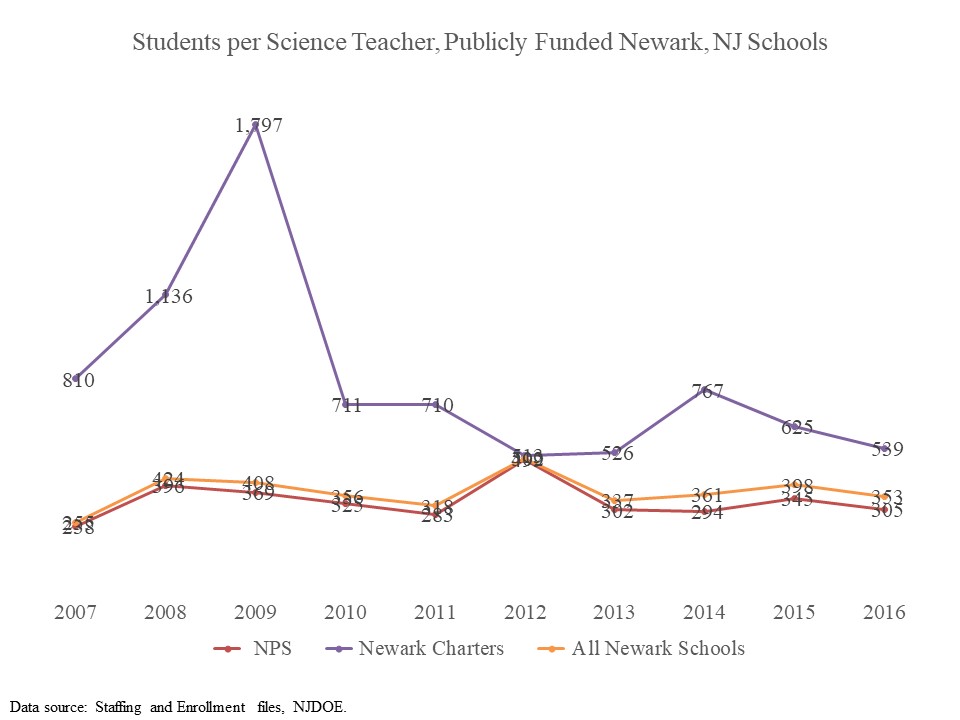

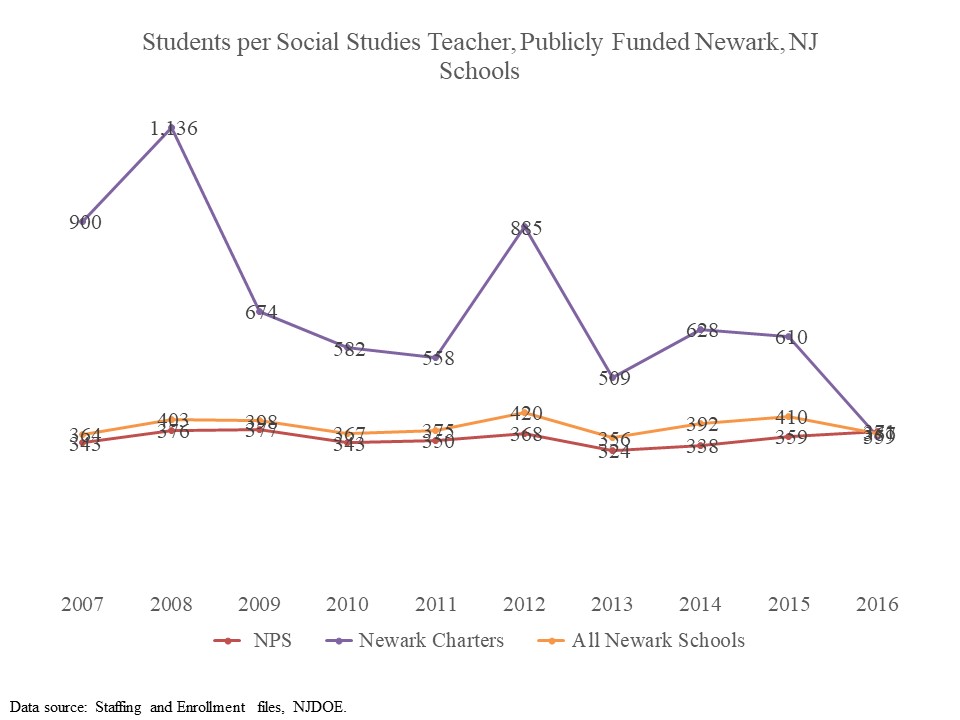

Programs in the arts, physical education, social studies, science, and other “non-tested” subjects require teachers who are certificated in those domains. To the extent that one school has fewer teachers (proportional to student enrollment) with a particular certification than another, we would assume that school offers less extensive programming within that certifications aligned field of study. Put simply: a school with more art teachers per 100 students will likely have more offerings in the arts.

We present here several graphs that show, over a ten-year period, how the Newark charter sector differs from the NPS district in how many teachers in particular subject areas are deployed. Our measure is “student loads”: the number of students each teacher certificated in a particular subject would have to teach if the students were all divided evenly among teachers.

Figure C15, for example, shows the student load for art teachers[v] in NPS schools, the charter sector, and all publicly funded Newark schools combined. In every year, art teachers in charter schools have much greater student loads than in NPS. While not definitive proof, this deployment of staff may indicate that charters do not offer coursework in art that is as extensive as NPS schools.

Figure C15

While this data does show significant volatility in the charter schools, the general trend across the past decade has been that Newark charter schools do not have as many staff per student in a variety of non-tested subjects.

One caution: part of the disparity in staff may be due to differences in grade enrollments. If charters, for example, enroll a smaller proportion of high school students, they may have less need for teachers with social studies certifications. We have begun a preliminary investigation into this possibility. As of now, we do not find that the percentage of Grade 9 to 12 students in a school fully explains the difference between NPS and charter schools. Further analysis, however, may yield different results.

Figure C16

Figure C17

Figure C18

Figure C19

Figure C20

[i] See, for example: https://relinquishment.org/2017/10/23/could-newark-have-achieved-more/

[ii] Winters, M. A. (2013). Why the gap? Special education and New York City charter schools. Manhattan Institute for Policy Research and Center for Reinventing Public Education.

Winters, M. A., Carpenter, D. M., & Clayton, G. (2017). Does Attending a Charter School Reduce the Likelihood of Being Placed Into Special Education? Evidence From Denver, Colorado. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 0162373717690830.

[iii] See, for example, the CREDO Urban Charter Schools study: http://urbancharters.stanford.edu/download/Urban%20Charter%20School%20Study%20Report%20on%2041%20Regions.pdf This study is cited by the reports to assert that “Newark is home to one of the most effective charter sectors in the nation in terms of student growth on standardized exams” (p. 19)

[iv] We thank Dr. Julia Sass Rubin of Rutgers University, Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, for the data.

[v] For each of the categories given, we consolidate job codes into larger categories. For example: “art teachers” include photography, ceramics, theatre/stage, dance, etc. We use the categories provided by NJDOE for guidance.