Below is a section of a paper I’ve been working on the past few weeks (which will be presented in Philadelphia in April)

Some of the content below is also drawn from: http://www.shankerinstitute.org/images/doesmoneymatter_final.pdf

===============

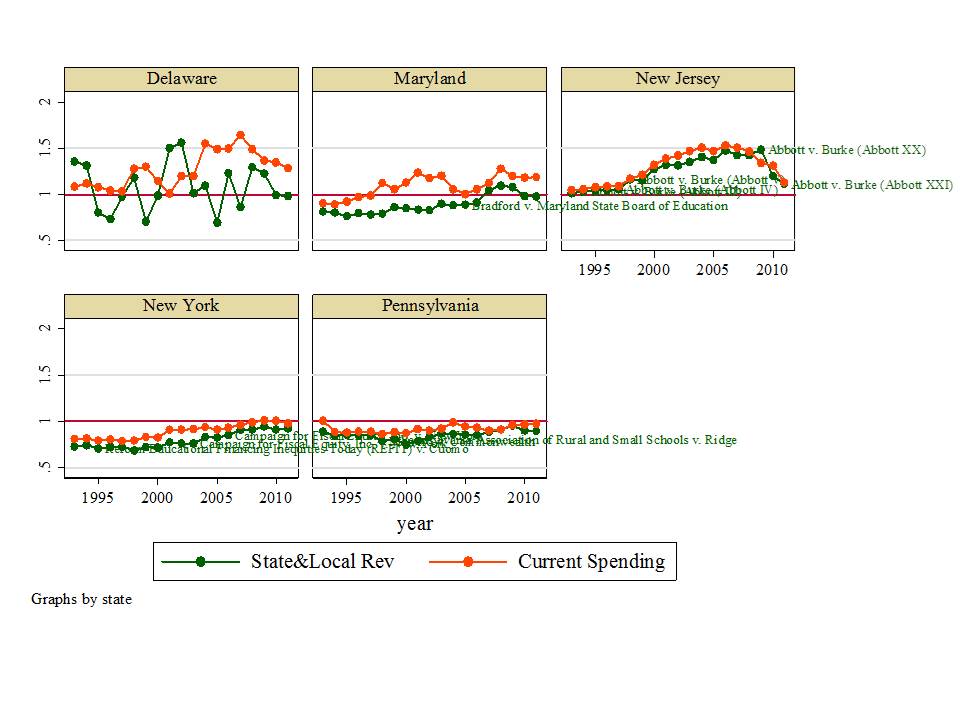

Over the past several decades, many states have pursued substantive changes to their state school finance systems, while others have not. Some reforms have come and gone. Some reforms have been stimulated by judicial pressure resulting from state constitutional challenges and others have been initiated by legislatures. In an evaluation of judicial involvement in school finance and resulting reforms from 1971 to 1996, Murray, Evans and Schwab (1998) found that “court ordered finance reform reduced within-state inequality in spending by 19 to 34 percent. Successful litigation reduced inequality by raising spending in the poorest districts while leaving spending in the richest districts unchanged, thereby increasing aggregate spending on education. Reform led states to fund additional spending through higher state taxes.” (p. 789)

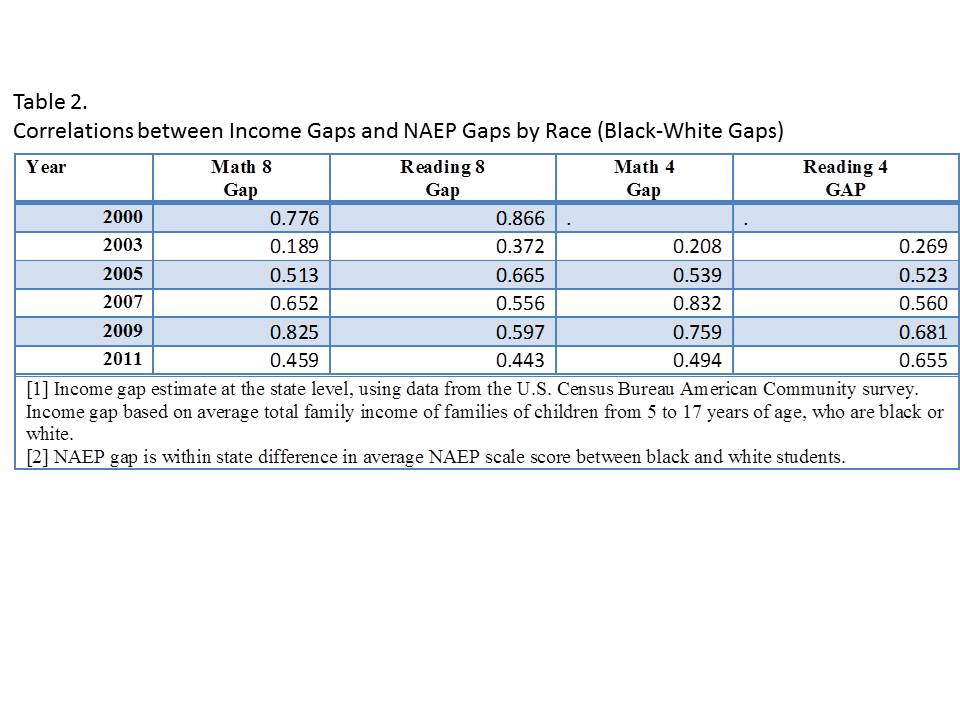

There exists an increasing body of evidence that substantive and sustained state school finance reforms matter for improving both the level and distribution of short term and long run student outcomes. A few studies have attempted to tackle school finance reforms broadly applying multi-state analyses over time. Card and Payne (2002) found “evidence that equalization of spending levels leads to a narrowing of test score outcomes across family background groups.” (p. 49) Jackson, Johnson and Persico (2014) use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to evaluate long term outcomes of children exposed to court-ordered school finance reforms, based on matching PSID records to childhood school districts for individuals born between 1955 and 1985 and followed up through 2011. They find that the “Effects of a 20% increase in school spending are large enough to reduce disparities in outcomes between children born to poor and non‐poor families by at least two‐thirds,” and further that “A 1% increase in per‐pupil spending increases adult wages by 1% for children from poor families.”(p. 42)

Figlio (2004) explains that the influence of state school finance reforms on student outcomes is perhaps better measured within states over time, explaining that national studies of the type attempted by Card and Payne confront problems of a) the enormous diversity in the nature of state aid reform plans, and b) the paucity of national level student performance data. Most recent peer reviewed studies of state school finance reforms have applied longitudinal analyses within specific states. And several such studies provide compelling evidence of the potential positive effects of school finance reforms. Roy (2011) published an analysis of the effects of Michigan’s 1990s school finance reforms which led to a significant leveling up for previously low-spending districts. Roy, whose analyses measure both whether the policy resulted in changes in funding and who was affected, found that “Proposal A was quite successful in reducing interdistrict spending disparities. There was also a significant positive effect on student performance in the lowest-spending districts as measured in state tests.” (p. 137) Similarly, Papke (2001), also evaluating Michigan school finance reforms from the 1990s, found that “increases in spending have nontrivial, statistically significant effects on math test pass rates, and the effects are largest for schools with initially poor performance.” (Papke, 2001, p. 821)[1] Deke (2003) evaluated “leveling up” of funding for very-low-spending districts in Kansas, following a 1992 lower court threat to overturn the funding formula (without formal ruling to that effect). The Deke article found that a 20 percent increase in spending was associated with a 5 percent increase in the likelihood of students going on to postsecondary education. (p. 275)

Two studies of Massachusetts school finance reforms from the 1990s find similar results. The first, a non-peer-reviewed report by Downes, Zabel, and Ansel (2009) explored, in combination, the influence on student outcomes of accountability reforms and changes to school spending. It found that “Specifically, some of the research findings show how education reform has been successful in raising the achievement of students in the previously low-spending districts.” (p. 5) The second study, an NBER working paper by Guryan (2001), focused more specifically on the redistribution of spending resulting from changes to the state school finance formula. It found that “increases in per-pupil spending led to significant increases in math, reading, science, and social studies test scores for 4th- and 8th-grade students. The magnitudes imply a $1,000 increase in per-pupil spending leads to about a third to a half of a standard-deviation increase in average test scores. It is noted that the state aid driving the estimates is targeted to under-funded school districts, which may have atypical returns to additional expenditures.” (p. 1)[2] Downes had conducted earlier studies of Vermont school finance reforms in the late 1990s (Act 60). In a 2004 book chapter, Downes noted “All of the evidence cited in this paper supports the conclusion that Act 60 has dramatically reduced dispersion in education spending and has done this by weakening the link between spending and property wealth. Further, the regressions presented in this paper offer some evidence that student performance has become more equal in the post-Act 60 period. And no results support the conclusion that Act 60 has contributed to increased dispersion in performance.” (p. 312)[3] Most recently, Hyman (2013) also found positive effects of Michigan school finance reforms in the 1990s, but raised some concerns regarding the distribution of those effects. Hyman found that much of the increase was targeted to schools serving fewer low income children. But, the study did find that students exposed to an additional “12%, more spending per year during grades four through seven experienced a 3.9 percentage point increase in the probability of enrolling in college, and a 2.5 percentage point increase in the probability of earning a degree.” (p. 1)

Indeed, this point is not without some controversy, much of which is easily discarded. Second-hand references to dreadful failures following massive infusions of new funding can often be traced to methodologically inept, anecdotal tales of desegregation litigation in Kansas City, Missouri, or court-ordered financing of urban districts in New Jersey (see Baker & Welner, 2011).[4] Hanushek and Lindseth (2009) use a similar anecdote-driven approach in which they dedicate a chapter of a book to proving that court-ordered school funding reforms in New Jersey, Wyoming, Kentucky, and Massachusetts resulted in few or no measurable improvements. However, these conclusions are based on little more than a series of graphs of student achievement on the National Assessment of Educational Progress in 1992 and 2007 and an untested assertion that, during that period, each of the four states infused substantial additional funds into public education in response to judicial orders.[5] Greene and Trivitt (2008) present a study in which they claim to show that court ordered school finance reforms let to no substantive improvements in student outcomes. However, the authors test only whether the presence of a court order is associated with changes in outcomes, and never once measure whether substantive school finance reforms followed the court order, but still express the conclusion that court order funding increases had no effect. In equally problematic analysis, Neymotin (2010) set out to show that massive court ordered infusions of funding in Kansas following Montoy v. Kansas led to no substantive improvements in student outcomes. However, Neymotin evaluated changes in school funding from 1997 to 2006, but the first additional funding infused following the January 2005 supreme court decision occurred in the 2005-06 school year, the end point of Neymotin’s outcome data.

On balance, it is safe to say that a significant and growing body of rigorous empirical literature validates that state school finance reforms can have substantive, positive effects on student outcomes, including reductions in outcome disparities or increases in overall outcome levels. Further, it stands to reason that if positive changes to school funding have positive effects on short and long run outcomes both in terms of level and distribution, then negative changes to school funding likely have negative effects on student outcomes. Thus it is critically important to understand the impact of the recent recession on state school finance systems, the effects on long term student outcomes being several years down the line.

References

Ajwad, Mohamad I. 2006. Is intra-jurisdictional resource allocation equitable? An analysis of campus level spending data from Texas elementary schools. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 46 (2006) 552-564

Baker, Bruce D. 2012. Re-arranging deck chairs in Dallas: Contextual constraints on within district resource allocation in large urban Texas school districts. Journal of Education Finance 37 (3) 287-315

Baker, B. D., & Corcoran, S. P. (2012). The Stealth Inequities of School Funding: How State and Local School Finance Systems Perpetuate Inequitable Student Spending. Center for American Progress.

Baker, B., & Green, P. (2008). Conceptions of equity and adequacy in school finance. Handbook of research in education finance and policy, 203-221.

Baker, B. D., Sciarra, D. G., & Farrie, D. (2012). Is School Funding Fair?: A National Report Card. Education Law Center. http://schoolfundingfairness.org/National_Report_Card_2012.pdf

Baker, B. D., Taylor, L. L., & Vedlitz, A. (2008). Adequacy estimates and the implications of common standards for the cost of instruction. National Research Council.

Baker, B. D., & Welner, K. G. (2011). School finance and courts: Does reform matter, and how can we tell. Teachers College Record, 113(11), 2374-2414.

Baker, B.D., Welner, K.G. (2010) Premature celebrations: The persistence of inter-district funding disparities. Education Policy Analysis Archives. http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/article/viewFile/718/831

Card, D., and Payne, A. A. (2002). School Finance Reform, the Distribution of School Spending, and the Distribution of Student Test Scores. Journal of Public Economics, 83(1), 49-82.

Chambers, Jay G., Jesse D. Levin, and Larisa Shambaugh. 2010. Exploring weighted student formulas as a policy for improving equity for distributing resources to schools: A case study of two California school districts. Economics of Education Review, 29(2), 283-300.

Chambers, Jay, Larisa Shambaugh, Jesse Levin, Mari Muraki, and Lindsay Poland. 2008. A Tale of Two Districts: A Comparative Study of Student-Based Funding and School-Based Decision Making in San Francisco and Oakland Unified School Districts. American Institutes for Research. Palo Alto, CA.

Ciotti, P. (1998). Money and School Performance: Lessons from the Kansas City Desegregations Experience. Cato Policy Analysis #298.

Coate, D. & VanDerHoff, J. (1999). Public School Spending and Student Achievement: The Case of New Jersey. Cato Journal, 19(1), 85-99.

Corcoran, S., & Evans, W. N. (2010). Income inequality, the median voter, and the support for public education (No. w16097). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Dadayan, L. (2012) The Impact of the Great Recession on Local Property Taxes. Albany, NY: Rockefeller Institute. http://www.rockinst.org/pdf/government_finance/2012-07-16-Recession_Local_%20Property_Tax.pdf

Deke, J. (2003). A study of the impact of public school spending on postsecondary educational attainment using statewide school district refinancing in Kansas, Economics of Education Review, 22(3), 275-284.

Downes, T. A., Zabel, J., and Ansel, D. (2009). Incomplete Grade: Massachusetts Education Reform at 15. Boston, MA. MassINC.

Downes, T. A. (2004). School Finance Reform and School Quality: Lessons from Vermont. In Yinger, J. (ed), Helping Children Left Behind: State Aid and the Pursuit of Educational Equity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Duncombe, W., Yinger, J. (2008) Measurement of Cost Differentials In H.F. Ladd & E. Fiske (eds) pp. 203-221. Handbook of Research in Education Finance and Policy. New York: Routledge.

Duncombe, W., & Yinger, J. (1998). School finance reform: Aid formulas and equity objectives. National Tax Journal, 239-262.

Edspresso (2006, October 31). New Jersey learns Kansas City’s lessons the hard way. Retrieved October 23, 2009, from http://www.edspresso.com/index.php/2006/10/new-jersey-learns-kansas-citys-lessons-the-hard-way-2/

Evers, W. M., and Clopton, P. (2006). “High-Spending, Low-Performing School Districts,” in Courting Failure: How School Finance Lawsuits Exploit Judges’ Good Intentions and Harm our Children (Eric A. Hanushek, ed.) (pp. 103-194). Palo Alto, CA: Hoover Press.

Figlio, D.N. (2004) Funding and Accountability: Some Conceptual and Technical Issues in State Aid Reform. In Yinger, J. (ed) p. 87-111 Helping Children Left Behind: State Aid and the Pursuit of Educational Equity. MIT Press.

Goertz, M., and Weiss, M. (2009). Assessing Success in School Finance Litigation: The Case of New Jersey. New York City: The Campaign for Educational Equity, Teachers College, Columbia University.

Greene, J. P. & Trivitt, (2008). Can Judges Improve Academic Achievement? Peabody Journal of Education, 83(2), 224-237.

Guryan, J. (2001). Does Money Matter? Estimates from Education Finance Reform in Massachusetts. Working Paper No. 8269. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hanushek, E. A., and Lindseth, A. (2009). Schoolhouses, Courthouses and Statehouses. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press., See also: http://edpro.stanford.edu/Hanushek/admin/pages/files/uploads/06_EduO_Hanushek_g.pdf

Hanushek, E. A. (Ed.). (2006). Courting failure: How school finance lawsuits exploit judges’ good intentions and harm our children (No. 551). Hoover Press.

Imazeki, J., & Reschovsky, A. (2004). School finance reform in Texas: A never ending story. Helping children left behind: State aid and the pursuit of educational equity, 251-281.

Jaggia, S., Vachharajani, V. (2004) Money for Nothing: The Failures of Education Reform in Massachusetts http://www.beaconhill.org/BHIStudies/EdStudy5_2004/BHIEdStudy52004.pdf

Leuven, E., Lindahl, M., Oosterbeek, H., and Webbink, D. (2007). The Effect of Extra Funding for Disadvantaged Pupils on Achievement. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(4), 721-736.

Murray, S. E., Evans, W. N., & Schwab, R. M. (1998). Education-finance reform and the distribution of education resources. American Economic Review, 789-812.

Neymotin, F. (2010) The Relationship between School Funding and Student Achievement in Kansas Public Schools. Journal of Education Finance 36 (1) 88-108

Papke, L. (2005). The effects of spending on test pass rates: evidence from Michigan. Journal of Public Economics, 89(5-6). 821-839.

Resch, A. M. (2008). Three Essays on Resources in Education (dissertation). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, Department of Economics. Retrieved October 28, 2009, from http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/61592/1/aresch_1.pdf

Roy, J. (2011). Impact of school finance reform on resource equalization and academic performance: Evidence from Michigan. Education Finance and Policy, 6(2), 137-167.

Sciarra, D., Farrie, D., Baker, B.D. (2010) Filling Budget Holes: Evaluating the Impact of ARRA Fiscal Stabilization Funds on State Funding Formulas. New York, Campaign for Educational Equity. http://www.nyssba.org/clientuploads/nyssba_pdf/133_FILLINGBUDGETHOLES.pdf

Taylor, L. L., & Fowler Jr, W. J. (2006). A Comparable Wage Approach to Geographic Cost Adjustment. Research and Development Report. NCES-2006-321. National Center for Education Statistics.

Walberg, H. (2006) High Poverty, High Performance Schools, Districts and States. in Courting Failure: How School Finance Lawsuits Exploit Judges’ Good Intentions and Harm our Children (Eric A. Hanushek, ed.) (pp. 79-102). Palo Alto, CA: Hoover Press.

Notes

[1] In a separate study, Leuven and colleagues (2007) attempted to isolate specific effects of increases to at-risk funding on at risk pupil outcomes, but did not find any positive effects.

[2] While this paper remains an unpublished working paper, the advantage of Guryan’s analysis is that he models the expected changes in funding at the local level as a function of changes to the school finance formula itself, through what is called an instrumental variables or two stage least squares approach. Then, Guryan evaluates the extent to which these policy induced variations in local funding are associated with changes in student outcomes. Across several model specifications, Guryan finds increased outcomes for students at Grade 4 but not grade 8. A counter study by the Beacon Hill Institute suggest that reduced class size and/or increased instructional spending either has no effect on or actually worsens student outcomes (Jaggia & Vachharajani, 2004).

[3] Two additional studies of school finance reforms in New Jersey also merit some attention in part because they directly refute findings of Hanushek and Lindseth and of the earlier Cato study and do so with more rigorous and detailed methods. The first, by Alex Resch (2008) of the University of Michigan (doctoral dissertation in economics), explored in detail the resource allocation changes during the scaling up period of school finance reform in New Jersey. Resch found evidence suggesting that New Jersey Abbott districts “directed the added resources largely to instructional personnel” (p. 1) such as additional teachers and support staff. She also concluded that this increase in funding and spending improved the achievement of students in the affected school districts. Looking at the statewide 11th grade assessment (“the only test that spans the policy change”), she found: “that the policy improves test scores for minority students in the affected districts by one-fifth to one-quarter of a standard deviation” (p. 1). Goertz and Weiss (2009) also evaluated the effects of New Jersey school finance reforms, but did not attempt a specific empirical test of the relationship between funding level and distributional changes and outcome changes. Thus, their findings are primarily descriptive. Goertz and Weiss explain that on state assessments achievement gaps closed substantially between 1999 and 2007, the period over which Abbott funding was most significantly scaled up. Goertz & Weiss further explain: “State Assessments: In 1999 the gap between the Abbott districts and all other districts in the state was over 30 points. By 2007 the gap was down to 19 points, a reduction of 11 points or 0.39 standard deviation units. The gap between the Abbott districts and the high-wealth districts fell from 35 to 22 points. Meanwhile performance in the low-, middle-, and high-wealth districts essentially remained parallel during this eight-year period” (Figure 3, p. 23).

[4] Two reports from Cato Institute are illustrative (Ciotti, 1998, Coate & VanDerHoff, 1999).

[5] That is, the authors merely assert that these states experienced large infusions of funding, focused on low income and minority students, within the time period identified. They necessarily assume that, in all other states which serve as a comparison basis, similar changes did not occur. Yet they validate neither assertion. Baker and Welner (2011) explain that Hanushek and Lindseth failed to even measure whether substantive changes had occurred to the level or distribution of school funding as well as when and for how long. In New Jersey, for example, infusion of funding occurred from 1998 to 2003 (or 2005), thus Hanushek and Lindseth’s window includes 6 years on the front end where little change occurred (When?). Kentucky reforms had largely faded by the mid to late 1990s, yet Hanushek and Lindseth measure post reform effects in 2007 (When?). Further, in New Jersey, funding was infused into approximately 30 specific districts, but Hanushek and Lindseth explore overall changes to outcomes among low-income children and minorities using NAEP data, where some of these children attend the districts receiving additional support but many did not (Who?). In short the slipshod comparisons made by Hanushek and Lindseth provide no reasonable basis for asserting either the success or failures of state school finance reforms. Hanushek (2006) goes so far as to title the book “How School Finance Lawsuits Exploit Judges’ Good Intentions and Harm Our Children.” The premise that additional funding for schools often leveraged toward class size reduction, additional course offerings or increased teacher salaries, causes harm to children is, on its face, absurd. And the book which implies as much in its title never once validates that such reforms ever do cause harm. Rather, the title is little more than a manipulative attempt to convince the non-critical spectator who never gets past the book’s cover to fear that school finance reforms might somehow harm children. The book also includes two examples of a type of analysis that occurred with some frequency in the mid-2000s which also had the intent of showing that school funding doesn’t matter. These studies would cherry pick anecdotal information on either or both a) poorly funded schools that have high outcomes or b) well-funded schools that have low outcomes (see Evers & Clopton, 2006, Walber, 2006).