Not long ago, the transition teams for our new governor released their reports including an extensive report on K-12 education reform strategies. In the area of school finance, the report recommended:

(great synopsis at: http://njleftbehind.blogspot.com/2010/01/cheat-sheet-for-christies-educational.html)

- Identify “immediate opportunities to eliminate waste and expenditures from practices…that are making no or only limited contribution to the quality of education for children.”

- Review the efficacy of Corzine’s School Funding Reform Act where, famously, “the money follows the child.” Establish an “expert task force” to assess N.J.’s “overall funding system.”

- Freeze salaries for all public employees, including pre K-12 teachers, for FY 2011.

- Support and adopt A-15/S-1861, which eliminates public votes on school budgets that come in below cap.

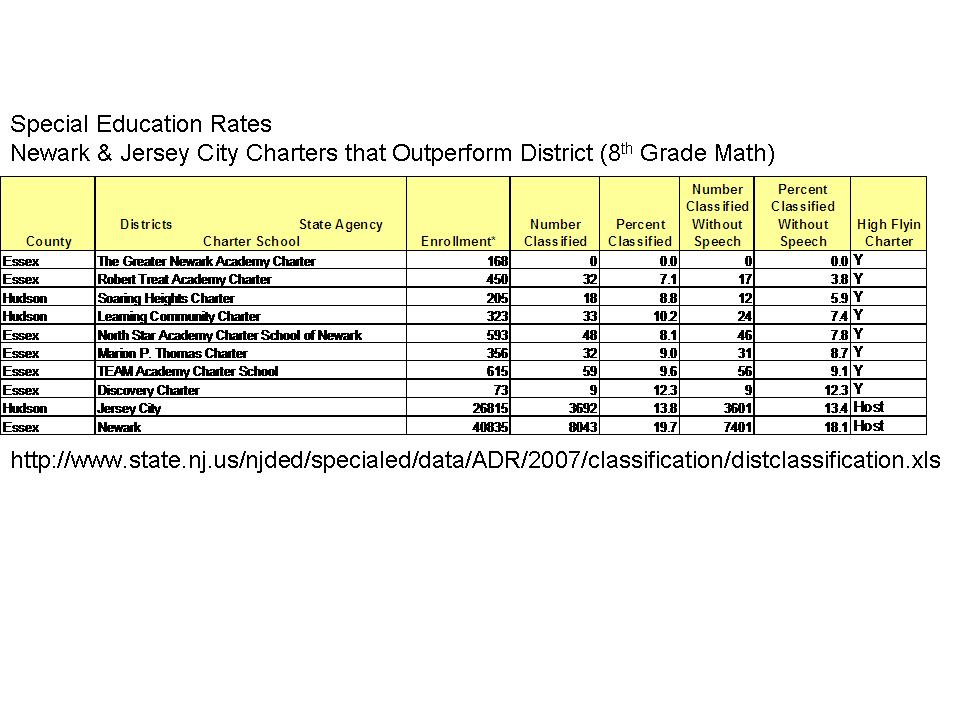

- Reduce costs in the “difficult area” of special education by limiting tuition increases at private out-of-district placements (currently 8-10% per year), shifting the burden of proof from local districts to parents when disputes arise regarding placements, and providing adequate state funding under IDEA to lift the financial burden off of local districts.

- When school districts and local bargaining units reach an impasse, allow districts the ability to invoke a “last best offer,” a practice in effect until the McGreevey administration.

- “Create regional salary guides to control escalating salary increases.”

- Figure out how to fund recurring expenditures now underwritten by ARRA money. Closely track the 327 million dollars due Jersey of Phase II ARRA money in FY 2010 budgets.

I’ll probably have something to say on each of these topics at some point in time, but for now, what caught my eye was the emphasis throughout these recommendations on the notion that New Jersey teacher salaries are “escalating” out of control: http://www.northjersey.com/news/state/012210_Teacher_staff_salaries_may_be_frozen_Christie_says.html

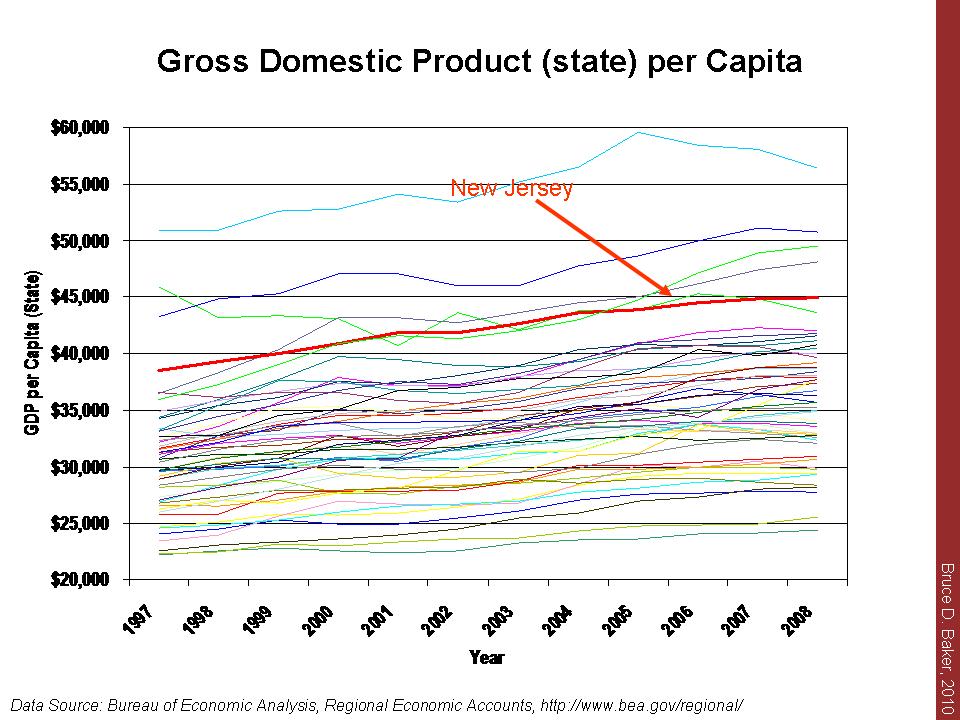

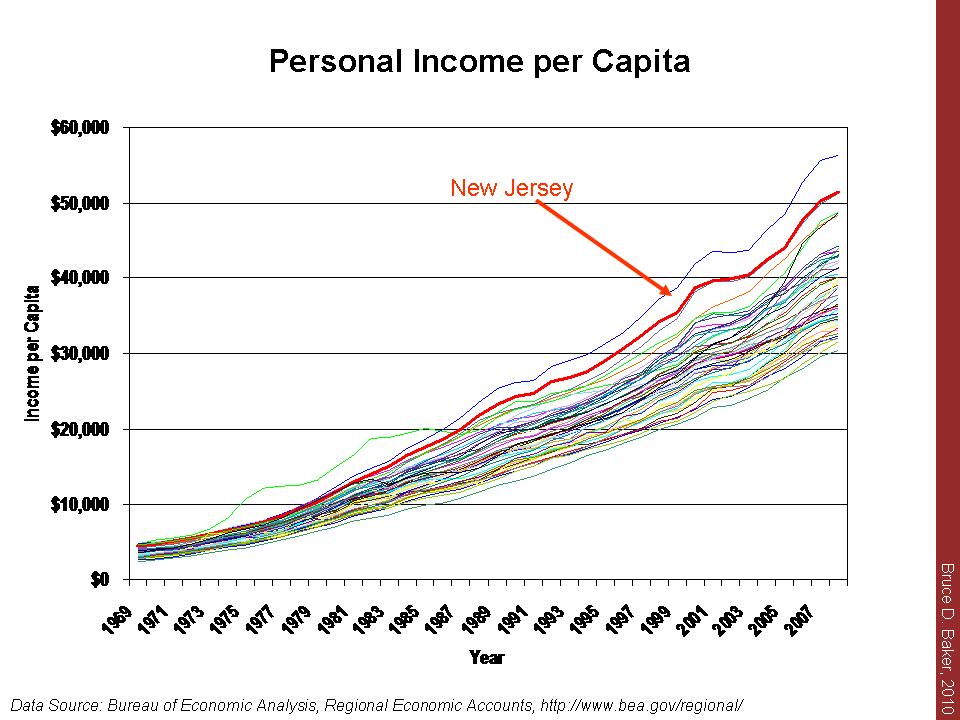

There seems to be much finger pointing that the budget crunch faced by local public school districts in New Jersey is driven by our supposed tops-in-the-nation teacher salaries and inappropriate increases to teacher wages in tough economic times (where these increases have occurred as a function of an imbalanced mediation process).

Let’s take a reasoned, data-driven (since that’s what we’re supposed to do) look at the question of whether New Jersey teacher salaries have, in fact, escalated out of control, and if so, where – what school districts/locations – are New Jersey teacher salaries most out of line, or in line?

I offer the following comparison bases:

1) How do New Jersey teacher salaries compare presently and over time with salaries of comparably qualified teachers in other states sharing the same labor market? That is, how do Northern New Jersey salaries compare not with all of New York State, but with teachers in the New York metropolitan area within New York State? Similarly, how do teacher salaries compare in the Camden area with those in the Philadelphia metropolitan area?

Unfortunately most available reports only compare state averages, and it’s much harder to easily access comparable teacher data across states which share a labor market. One data set that makes this possible is the National Center for Education Statistics, Schools and Staffing Survey, which has been administered in 1987-88, 1990-91, 1993-94, 1999-00, 2003-04, 2007-08. This is a data set I use frequently, but one which requires a special license and involves disclosure approvals (so I can’t just go posting fun, detailed findings here. Darn!). I urge the current NJDOE to get a license for these data and explore the question of how NJ teacher salaries compare to those of comparable teachers in the same labor market. I’ve not looked yet at the Philadelphia labor market, but I have looked at NY, NJ, CT in the past and have generally found that NEW JERSEY TEACHER SALARIES AT COMPARABLE QUALIFICATIONS, LAG BEHIND NEW YORK SUBURBAN SALARIES, AND HAVE FALLEN FURTHER BEHIND OVER TIME. Recently, NJ salaries seem to have slipped behind Southern CT salaries. This is also true of administrator salaries. Ford Fessenden has written on this topic in the past:

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/10/nyregion/nyregionspecial2/10mainwe.html

As I noted to Ford Fessenden in this article, between 1998 and 2005 in particular, “The data suggest that New York is outbidding its neighbors for the best teachers and administrators.” (this was also based on analysis of statewide teacher database data, but my current NY data file only goes through 2003).

UPDATE: I finally got the chance to run some appropriate comparisons of NY and NJ teacher salaries which validate Ford Fessenden’s and my own previous findings. see: https://schoolfinance101.wordpress.com/2010/04/12/teacher-salaries-in-nj-and-ny-counties/

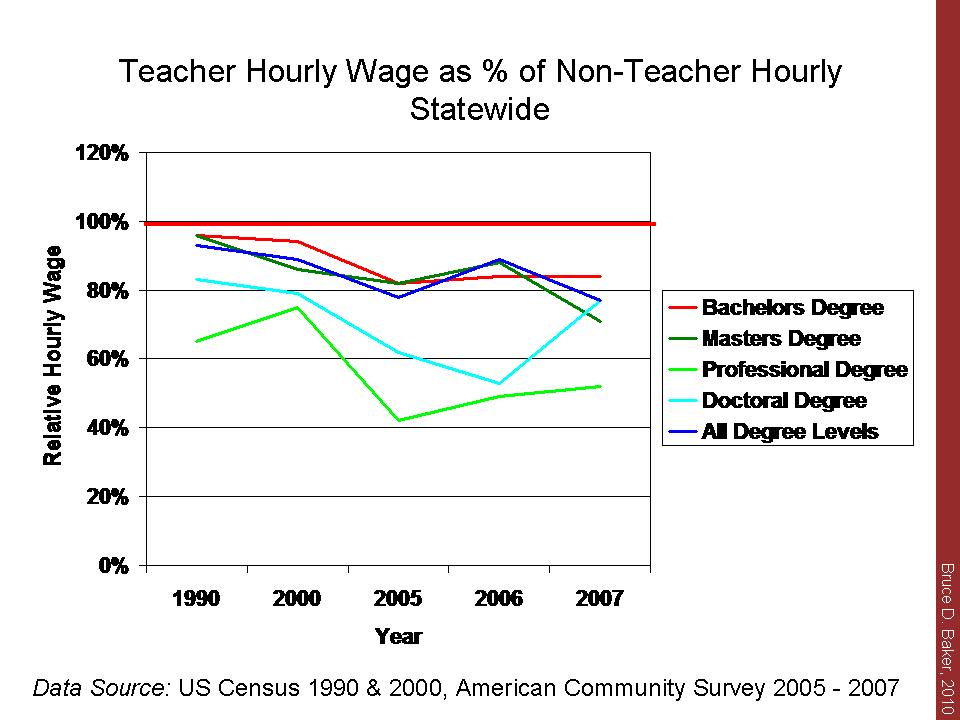

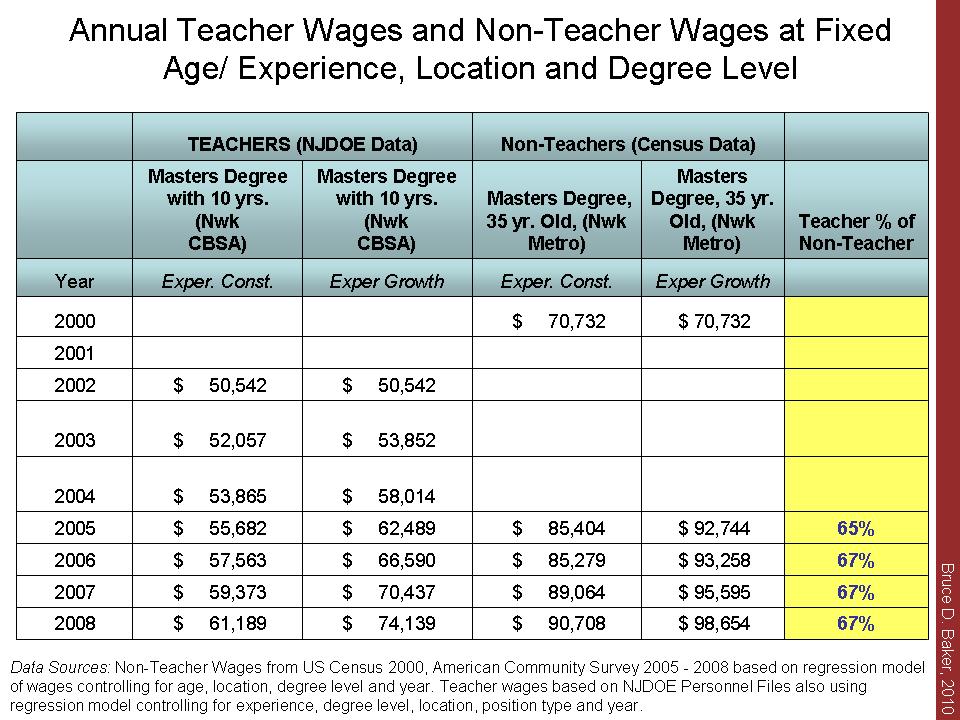

2) How do New Jersey teacher salaries compare with salaries of non-teachers a) in the same labor market, b) at the same age, c) at the same degree level and d) for the same amount of hours worked per day and days worked per year?

I’ve blogged on this topic in the past, pointing out that in New Jersey, based on U.S. Census and American Community Survey data on income from wages, teachers in New Jersey actually used to be – at one time – compensated quite similarly to their non-teacher peers on an hourly basis. That is, back around 1990. But, over time, New Jersey teacher salaries have slid further behind their non-teacher peers (though they have somewhat stronger average benefits packages. See my previous posts on teacher wages).

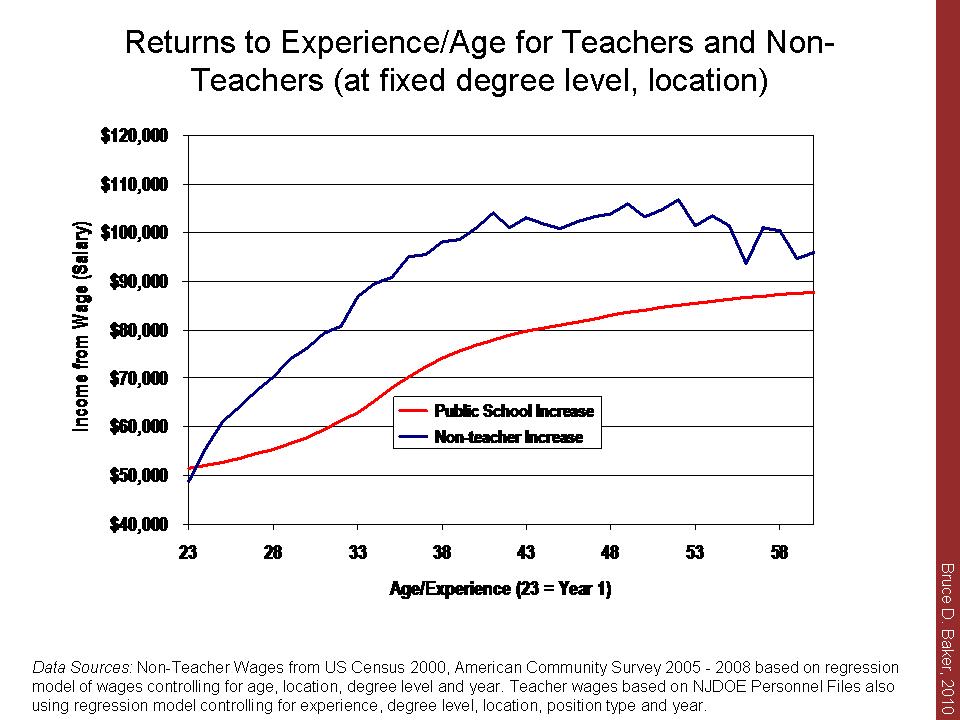

Here are my latest graphs on the topic – first, hourly wages over time by degree level and second, a modeled projection of teacher and non-teacher wages controlling for age, degree level, labormarket, hours worked and weeks worked. The first graph clearly shows that teacher salaries have slid from near 100% (near even) with non-teacher salaries back in 1990 for those with a BA only, to around 80% of the hourly wage of non-teachers with a BA. At other degree levels, teachers have fallen below 80%.

The second graph shows the projected annual wage for a 40 year old working 40 hours per week and 40 weeks per year, at the BA and MA level. This graph actually shows non-teachers with a BA surpassing teachers with an MA at the end of the period.

Note regarding benefits & bias: Corcoran and Mishel point out here: http://epi.3cdn.net/05447667bb274f359e_zam6br3st.pdf that

…overall K-12 teacher compensation was 27.5% greater than teacher wages alone, while overall professional compensation was 23.5% greater than professional wages. These differences in benefit shares translate into a benefits “bias”of 2.8 percentage points in 2006.

That is, benefits would close little of the overall gap in wages. Costrell and Podgursky show about a 5% (slightly less) differential (10% non-teachers, 15% teachers) in the value of pensions, a portion of benefits. This too would close only part of the teacher to non-teacher wage gap in New Jersey, even if we assume New Jersey benefits for teachers to be much greater than other employee benefits.

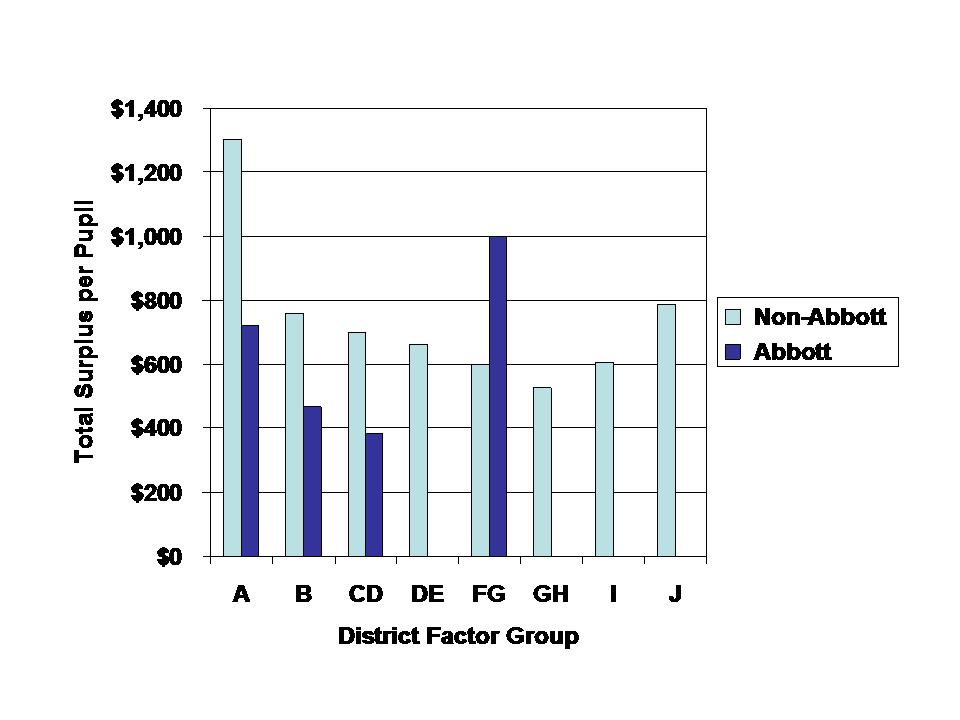

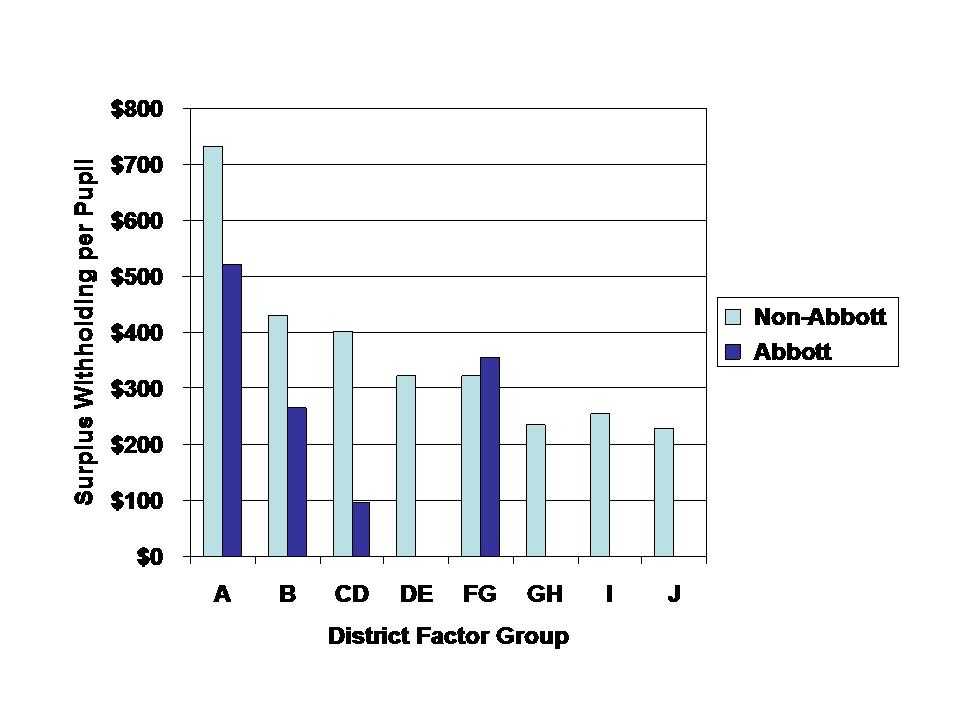

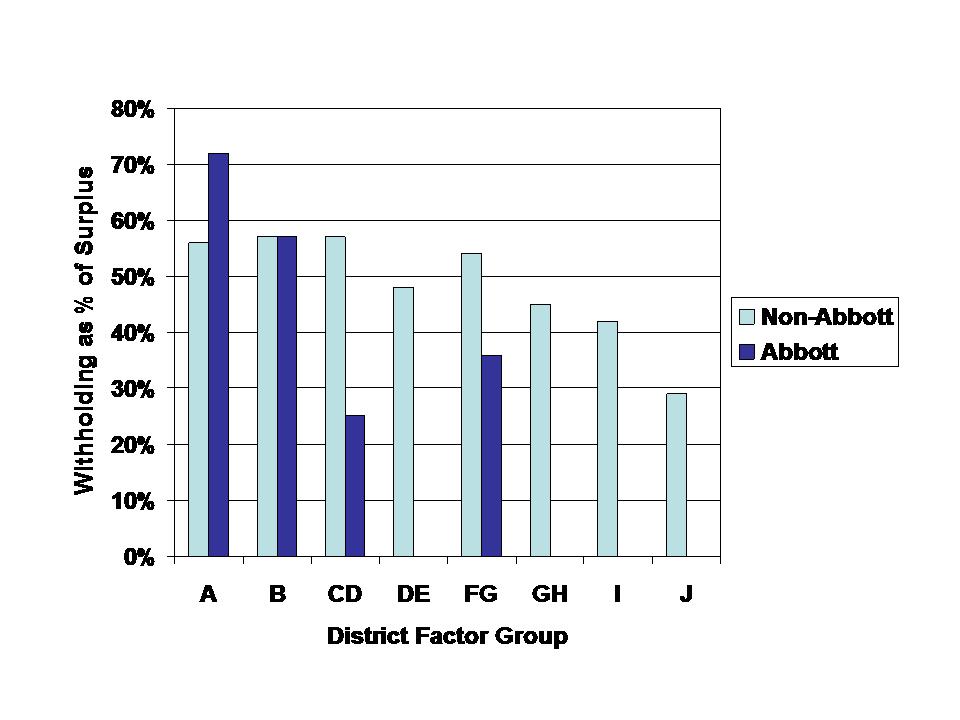

3) Where are those teacher salaries getting most out of line and what are the implications for property taxes? Is it really because the state has dumped so much funding into those Abbott districts? Or might it be because districts with high income families have chosen to adopt school district budgets which support higher salaries (essentially, canceling out the intended teacher recruitment edge produced by Abbott funding, if there ever was such a competitive edge)?

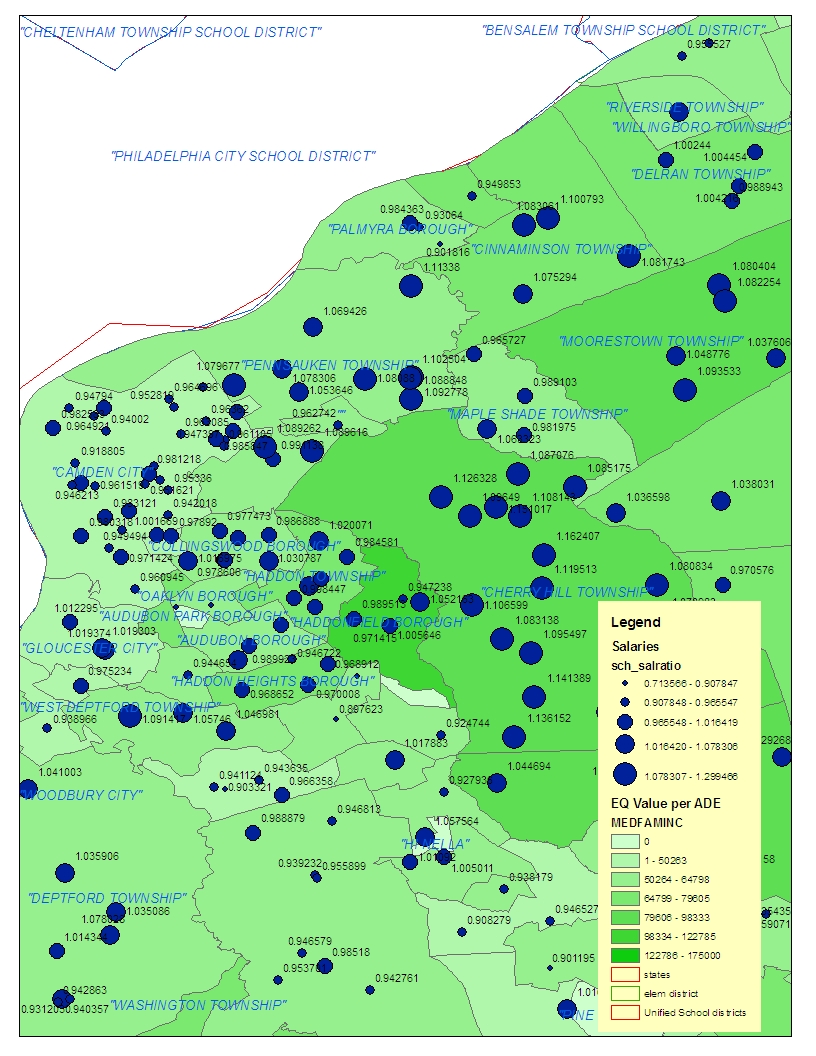

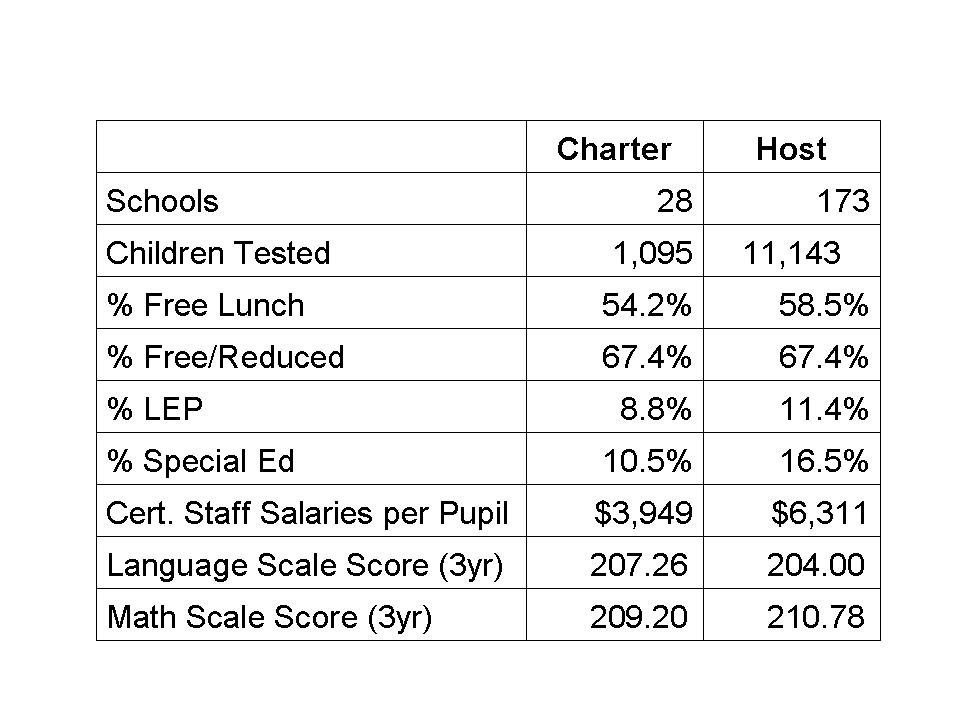

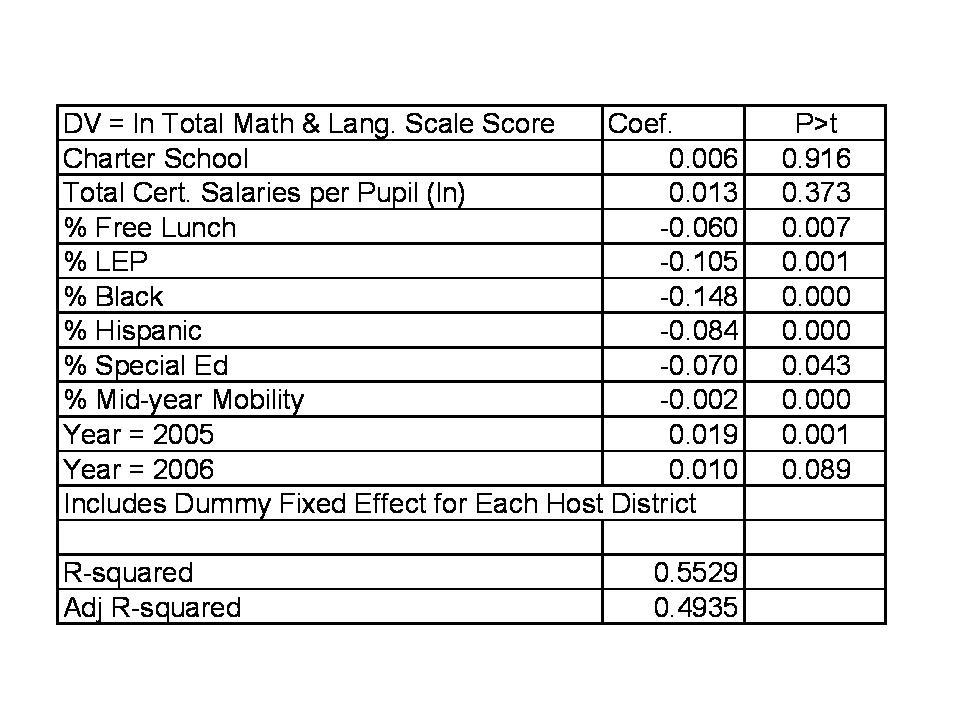

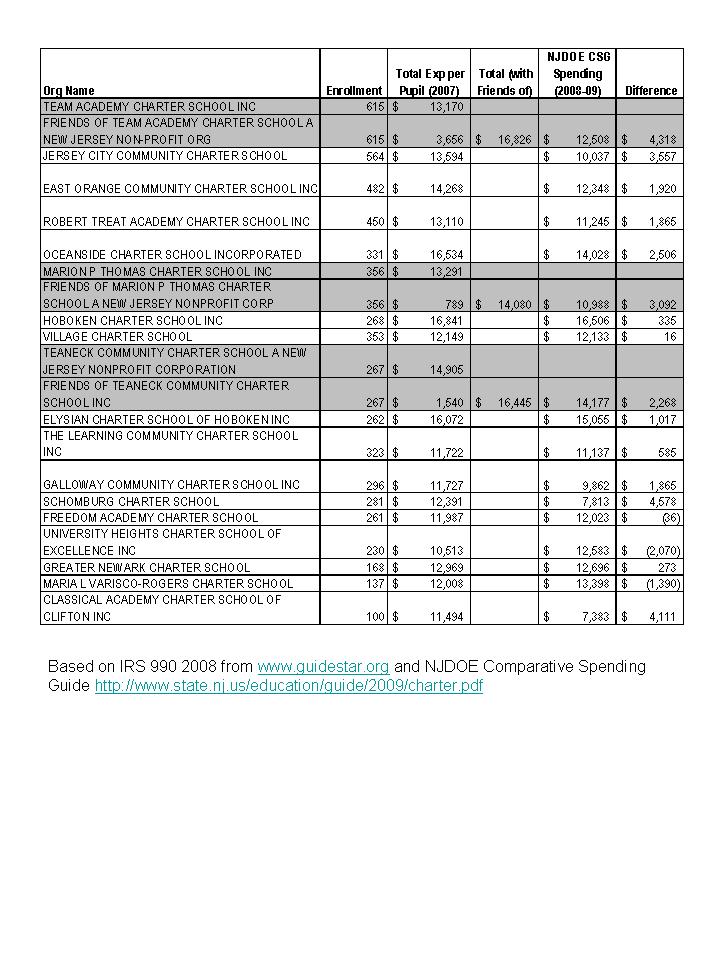

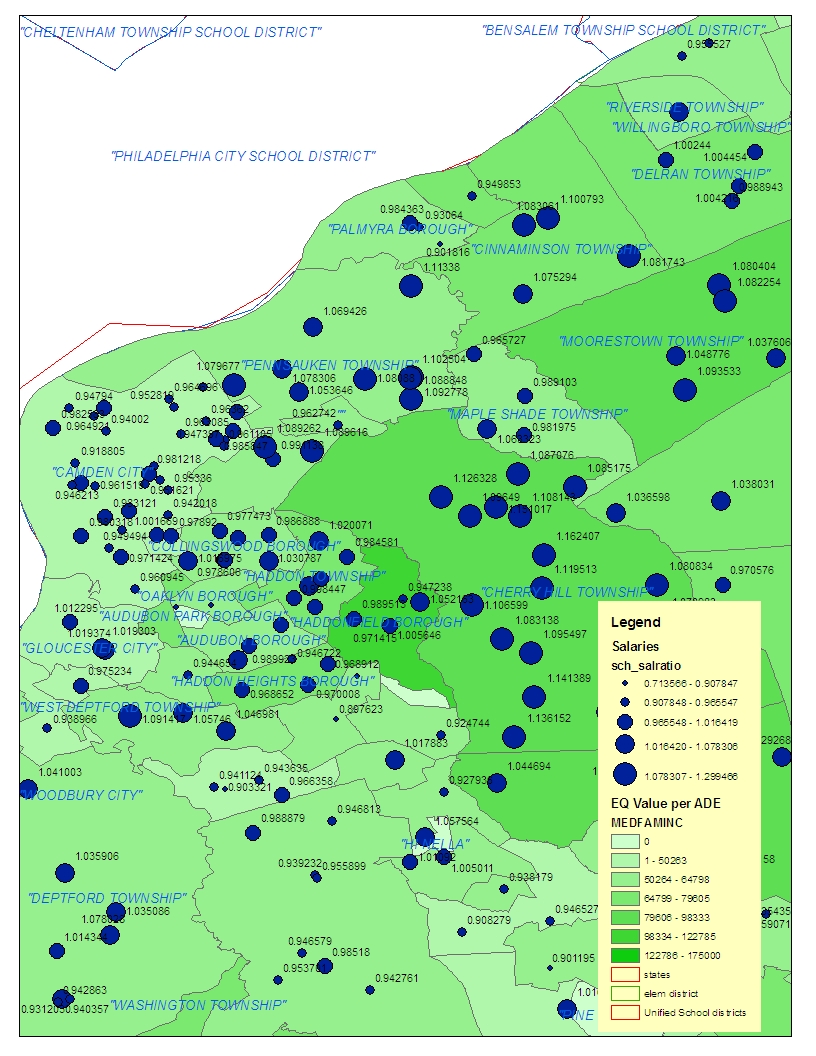

Because I love maps (see charter post), here are some maps of the school level relative competitiveness of teacher salaries – blue circles, overlaid on the median family income of school districts. The blue circles indicate the “relative competitiveness” of teacher salaries in a given school with a larger circle indicating that the actual salaries in that school are greater than the average predicted salaries for teachers with the degree and experience level of teachers in those schools. Schools are compared against others in their own labor market. So, a school identified as a large blue circle, or 1.05 value is a school where teacher salaries are 5% above the average expected salaries for those teachers in that labor market. Note that very low income, high minority urban schools would generally require higher salaries simply in order to recruit and retain comparable teachers. These maps, and competitiveness ratios include only New Jersey districts compared against other New Jersey districts. They do not include, for example, New York state districts which have much higher salaries for comparable teachers.

The first map shows the Newark area, and indeed Newark public schools do have relatively strong salaries, running at about 5% above expected. However, this margin is unlikely to yield teacher equity between Newark and its surroundings. Note that the many of the largest circles and highest competitiveness ratios – 1.12 to 1.14 – are in far more affluent suburbs like Millburn and Livingston. These self-inflicted higher salaries in districts that already provide more favorable working conditions create a competitive disadvantage for all other neighboring districts. The second map below shows the Camden area, where Camden teacher salaries are relatively non-competitive (as the district has increased quantities of staff rather than salaries over time) and where surrounding higher income suburbs have outpaced Camden city and other middle class suburbs.

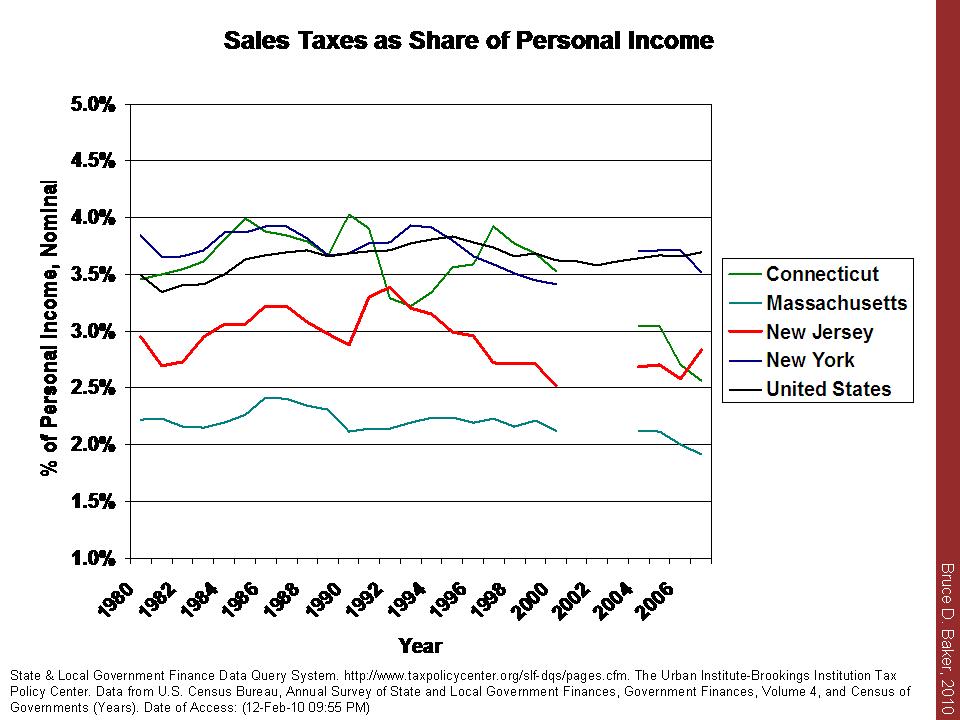

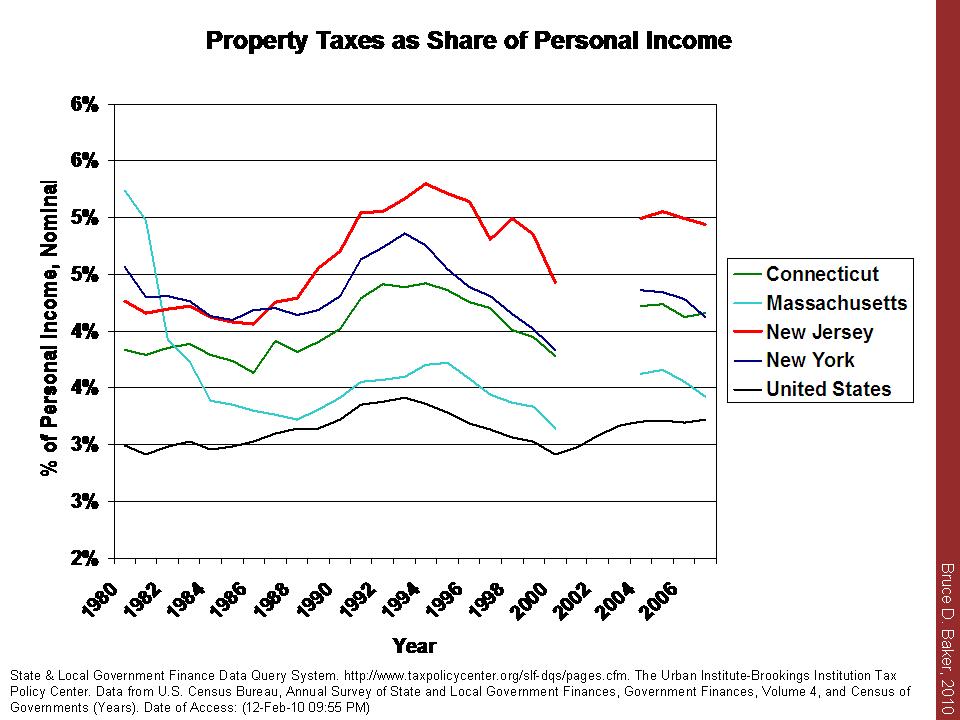

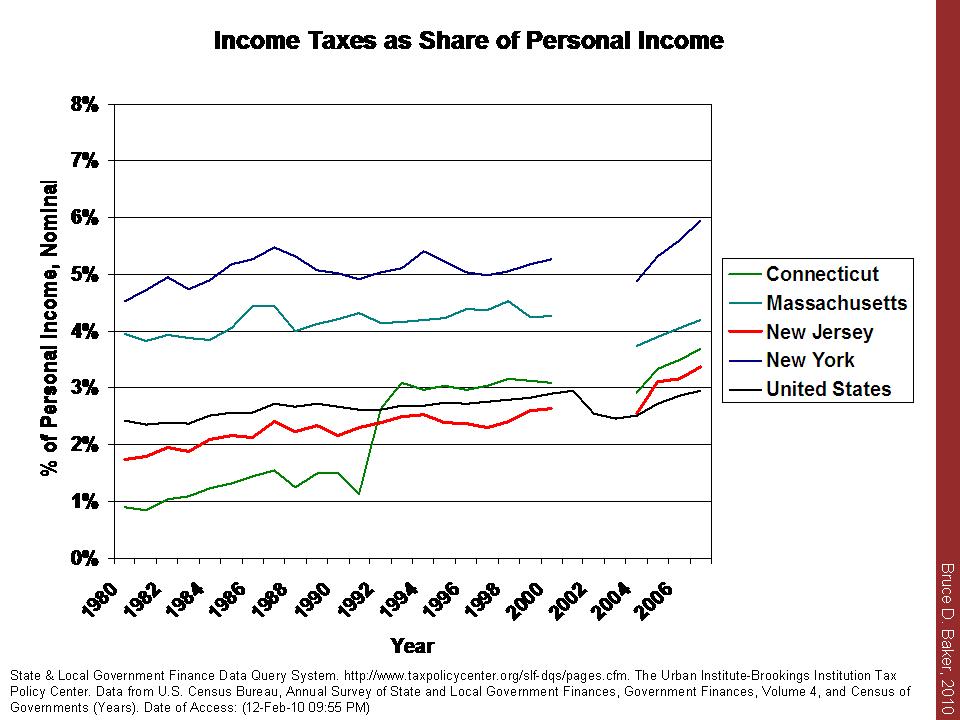

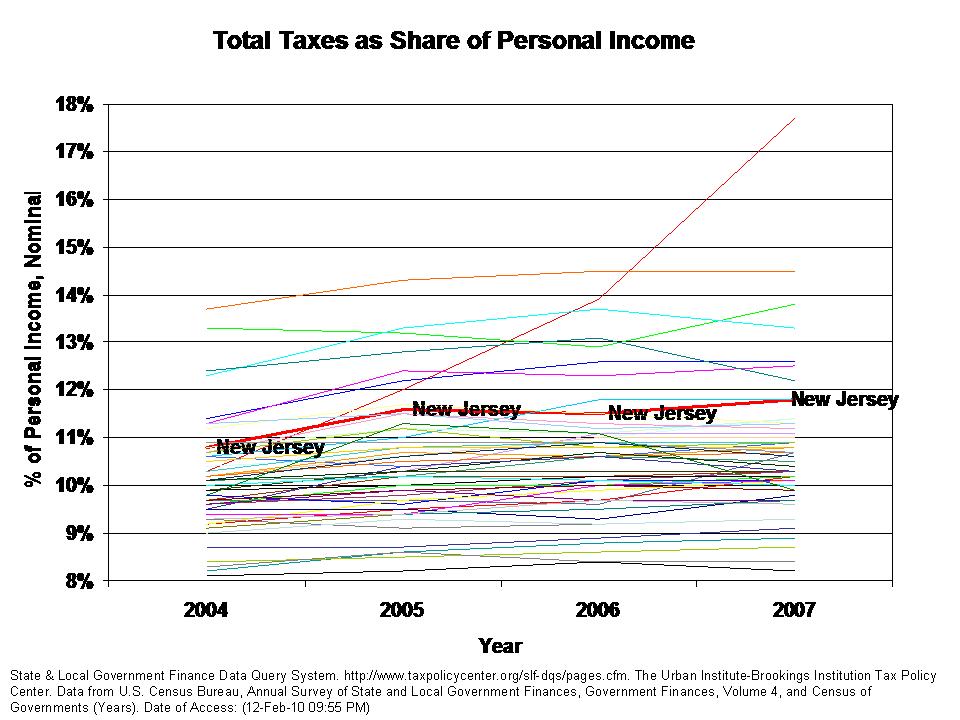

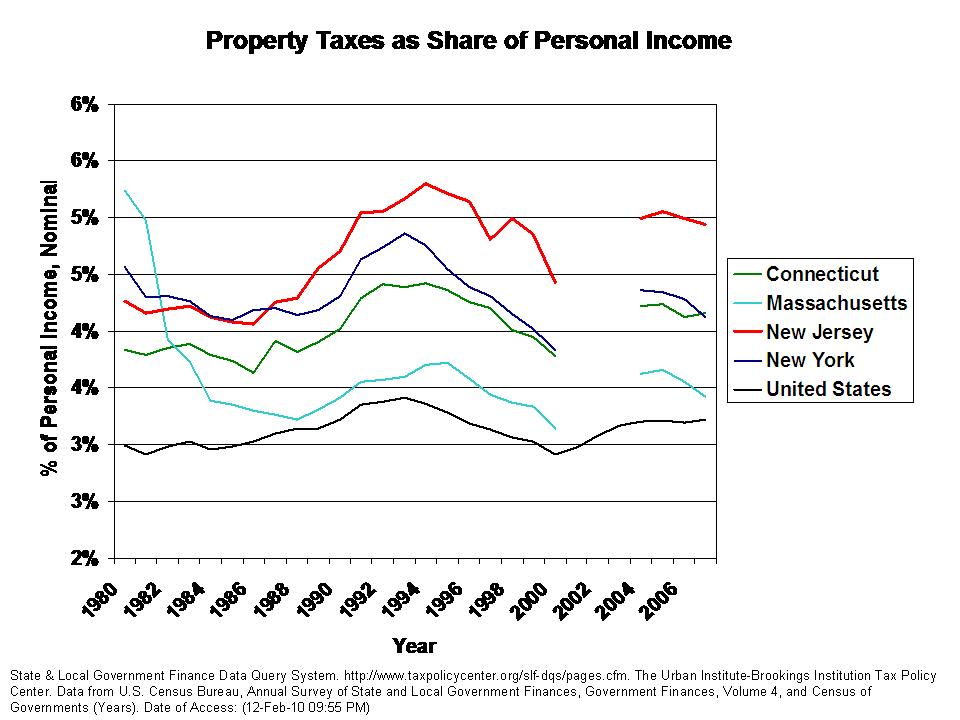

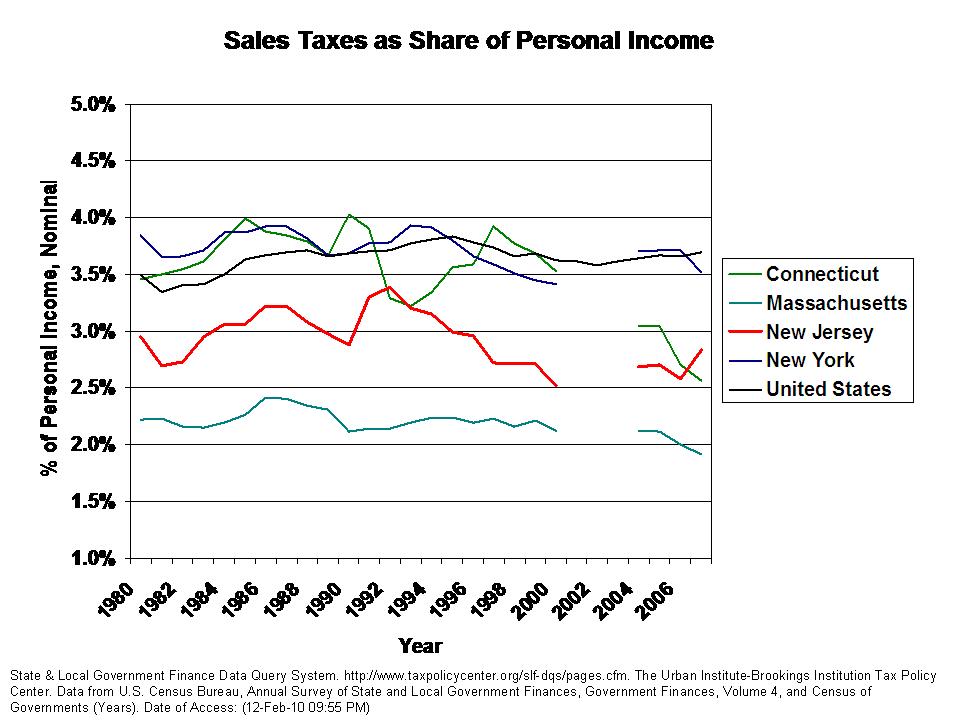

This does all raise some fun questions regarding the property tax debate. One might argue that these high spenders are doing so on property taxes – high property taxes in fact. Actually, my previous analyses show that these wealthy communities with high teacher salaries actually have lower property taxes as a percent of income. If there is a squeeze going on here, that squeeze is at the juncture of the relatively lower teacher salaries and relatively higher local property tax burden (as a share of income) in middle to lower middle wealth communities who are trying to keep up with their affluent neighbors, but are less reliant on state aid than poor urban districts.

This does all raise some fun questions regarding the property tax debate. One might argue that these high spenders are doing so on property taxes – high property taxes in fact. Actually, my previous analyses show that these wealthy communities with high teacher salaries actually have lower property taxes as a percent of income. If there is a squeeze going on here, that squeeze is at the juncture of the relatively lower teacher salaries and relatively higher local property tax burden (as a share of income) in middle to lower middle wealth communities who are trying to keep up with their affluent neighbors, but are less reliant on state aid than poor urban districts.

So, to conclude this rant – I’m having some trouble accepting the basic assumption that New Jersey teacher salaries are spiraling out of control, on either of the first two bases I discuss above. And further, I’m having some trouble accepting the notion that the spiraling salaries are a function of a statewide teachers’ union and strongly imbalanced mediation process. Rather, it would appear to me that very high income districts are simply choosing to spend what they can, and that it may be reasonable for these very districts to cut back, if their communities wish to do so. Actually, from a state policy perspective and especially from an equity perspective, if the current administration wishes to maintain the critical leverage provided by poverty-based funding to poor urban districts, the administration might wish to take a look at holding back the salary growth in the most affluent neighbors of the poorest urban districts. But, the notion that interventions are required to hold back all teacher salaries (with emphasis on those runaway urban districts) seems misguided.

See also: http://greatlakescenter.org/docs/Think_Twice/TT_Manhattan_Teacher%20Pay.pdf

for a discussion of technical problem’s with Jay Greene’s teacher salary analysis which is often used to argue that teachers are very well paid on an hourly basis. This is not directly relevant herein, because the analysis above deals with NJ teachers specifically, and uses more appropriate data for such analysis (the same data used by the National Center for Education Statistics for estimation of regional wage variation and for estimating teacher wages relative to other professional wages here: https://bush.tamu.edu/research/workingpapers/ltaylor/Comparing_Teacher_Salaries.pdf )